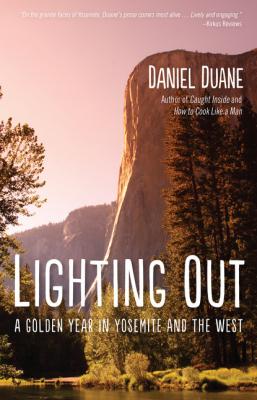

Lighting Out. Daniel Duane

Читать онлайн.| Название | Lighting Out |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Daniel Duane |

| Жанр | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781594859229 |

“Well, they just think it’s all happy, mellow white people signing petitions. Seems pretty real to me, and I don’t see why living in a pretty place can’t be real. It’s kind of a direction I want to go, anyway.” She looked at my sandals for a moment. I mentioned the skepticism of the editorial board toward the whole notion of California. She’d never lived anywhere else, but liked California pretty well.

“Also, destructive relationships with men,” she said, “had a lot to do with my moving down there.”

We sat together on the carpet in the pack room, mannequins swinging ice axes into the Romanesque vaults overhead, and she talked about a house of skylights in a Santa Cruz redwood grove, how she mountain biked to campus every morning on dirt trails with breezes blowing off the Pacific. Her first class was yoga in an octagonal red-wood-and-glass room out in a meadow—so powerful she had to walk her bike afterward for fear of crashing.

In the end, Kyla decided to just rent a backpack and think about buying one later; after all, it was a big investment. She hesitated for a moment, blinking at the sunlight beyond the door, the empty old rental pack on her back, then waved good-bye with her slender fingers and walked out. I stood for a moment and watched her walk down the steps and into the old Ghia. Just as she pulled out, with the top down on that funky, curvy old car, she caught me looking at her. She smiled just slightly to herself, and drove off. I ran back through the shop, past the Gore-Tex jackets and telemark ski boots, past the rock-climbing shoes and ice axes and straight into the rental area. I pulled her triplicate rental form back out of the accordion file, glanced around, and copied down her work number.

7

The next morning was foggy and cold, and I drove my pickup clear across congested Berkeley to just happen by the French bakery where Kyla worked. Among antique cases of exquisite morning buns and walnut-raspberry scones, kiwi tarts and strawberry tartlettes, she waited on a line of unhurried pensioners and frantic commuters. With beads braided into her cloud of uncombed blond hair and six earrings in her left ear, she described with perfect ease how they rolled out the croissant dough again and again to layer in the butter. She glanced up as I walked in, but went on selling a cappuccino and brioche to an old woman in a cashmere coat.

“I was wondering,” I said, when she had a moment free, “if you’d get a drink with . . .” She was shaking her head. “What?” I asked.

“I really don’t like bars,” she said. She leaned forward on the counter and looked at me carefully.

“A cup of coffee?” I asked. “No?” She shook her head again. “You don’t drink coffee? Well . . . you could get tea! Even herbal tea, I’m sure . . .”

“How about just a walk?” she asked. She smiled with the corners of her mouth, though not with her eyes.

“A walk? You mean . . . go walking?”

“Yeah. A walk. In the woods, tonight.”

“I . . . I’d love to. I love walking.”

She picked me up at my parents’ house and we drove up into the Berkeley Hills. We strolled out a fire road with a view of San Francisco’s lights reflected in the black pool of the bay. I remembered Mom telling me about coming up here to make out with Dad when they were in college. Kyla’s black cowboy boots gave her a swinging stride, though they kept slipping on smooth spots. In a eucalyptus grove there were caches here and there of homeless people’s possessions. Kyla said the trees were from Australia and had crowded out a lot of native species. A sallow man in a three-piece suit who was lying on the springs of a rotting couch paid little attention to us. Without pedantry, she pulled leaves off plants and offered them to taste—mugwort, yerba santa, sage—some bitter, some sweet. I’d hiked in those hills since I could walk and had never known the names of anything except poison oak and blackberries.

Lying in a meadow and bundled up inside her black turtleneck sweater, Kyla pointed out Orion and the Seven Sisters. She said she was an Aquarius, but didn’t know where that was in the sky.

“Apparently,” she said with mock-intimacy, “Aquarius means I’m independent and unattached, capricious and whimsical but not fiery. Can’t, I assure you, be held down.”

“Is that what you’re like?”

“I don’t know. Maybe.”

Trying to sound neither convinced nor mocking, I offered that I was a Scorpio. She didn’t respond. I waited a while, wondering as much how I’d meant the offer as about how she’d taken it. Maybe she was trying to remember the chemistry between Aquarians and Scorpios. Maybe it was supposed to be terrible. Or great. Or maybe she had no idea.

“Do you do a lot with astrology and crystals and stuff?” I asked. There was a pause while she thought about it. A siren sounded in the city below and I tried to make up my mind what I’d think if she said yes. My girlfriend in college, now working eighty-hour weeks in Manhattan, would’ve howled with laughter.

“Sometimes,” she said. I waited a few minutes again. She didn’t elaborate. Must just be second nature to her, I thought, and maybe that isn’t so bad. Then she coughed lightly and said, “Yeah, funny stuff, huh? But there must something in it.”

“Yeah, I’ve thought about it some too,” I said, which wasn’t really true. “This old hippy friend of my mom’s said I was the only one in our family with an ancient soul. She said I’d been around a long time. Like pretty much since the beginning.” That part was true. My folks had been a little put off because the sage hadn’t had nearly as much to say about them.

“Hmm,” she responded, without looking at me. She twirled a strand of hair between her fingers, her eyes still on the stars. I looked at her profile for a while, wondered whether she was serene or just shy. She didn’t look back. I never had the guts to try kissing on first dates, and anyway, I had no idea what Kyla’d think if I did. I might have seemed like just another one of those over-aggressive guys she’d had enough of.

As she drove the Ghia through the forest, both of us freezing in the wind and the radio blaring Led Zeppelin, she rocked her head up and down and laughed at the music. She said she was going up to Yosemite for a few days, and maybe she could see me when she got back. I was going to Yosemite too, to climb, and I asked if we could meet in a meadow one day. I could show her how to climb, or maybe we could camp together or cook a meal. She’d love to, she said, but it was a women’s music festival she was going to and a girlfriend had bought her the ticket.

8

Nicholas Cohen put a bare, hairy foot up on the dirty dashboard of my pickup and talked about the college back East where he’d just dropped out. I stayed in the passing lane south out of forested, foggy Berkeley and through sprawling, asphalt Oakland. No love lost, Nick said, but just like me he was psyched to be home. Then, six-lane Route 580 cut east out of the Bay Area and dry California grass appeared on hills denuded, reshaped, terraced; blasted out for the highway. In the valleys of the coastal range, housing tracts started and the air became dry and hot: California proper. Hundreds of square miles of just-add-lots-of-water neighborhoods.

“The clincher,” Nick said, “was when this Betty-no-brainer sorority girl, or chick, or . . . woman, or whatever, that I met at a frat party. I only talked to her for a minute. She calls me up out of the blue and says, like she’s going to make my year, ‘Nick, I’ve talked to some guys I know, and I really, honestly think you’re Sigma Chi material. I mean that.’ I almost got hives.” Nick rolled down the window and wiped dust off his gold wire-rimmed glasses. He wore a batiked polo shirt that made his gray eyes seem faintly purple. He actually was Sigma Chi material and was trying to fight it. Something about the attendant expectations of machismo were too much for him; he’d been trying to figure out how to tell his parents he wanted to paint, to make things with his hands. Handsome as hell, his only vanity was around his looks—otherwise he was petrified of criticism.

An isolated tract of faux-brick townhouses crowded against an oak forest; without a car and a tank of gas you wouldn’t