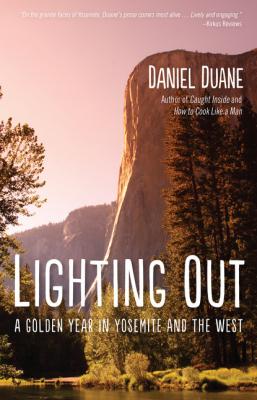

Lighting Out. Daniel Duane

Читать онлайн.| Название | Lighting Out |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Daniel Duane |

| Жанр | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781594859229 |

3

Hoping to find my dad and Uncle Sean up rock climbing in Yosemite, I packed my little blue pickup and drove out through the orchards and vineyards of the Central Valley toward Groveland. At Yosemite Junction in the foothills, the big range rippling up out of California’s Kansas, I went south in the summer heat to where the Tuolumne River—a big, splashing stream running over white granite boulders and slabs—cut under a bridge.

I hit the brakes at a dusty turnout, hopped out, and grabbed a towel and a guitar. My sandals picking up pebbles the whole way down, I walked through poison oak and blackberry bushes to a swimming hole. An off-duty road crew had strung a steel cable from high rocks on one side of the deep pool to oak trees on the eroding hill opposite; a thick, frayed rope hung from the cable’s midpoint down to the water. Coming up here with my mom, dad and sister when I was a kid, I’d thought of that cable as being about fifty, maybe even sixty feet off the water. Dad had to be crazy to climb out on it, swinging around like the teenagers. Mom would dive from some pretty high rocks, but she stayed away from the cable. He’d hang out there in space with his Levis on, kicking his feet around and whooping, then let go and slap into icy snow-melt water. As I got closer to the pool, I started dropping my height estimate on the cable, remembering that my preschool playground had recently turned out to be only about half an acre—not the two or three square miles I recalled. Sure enough—twelve feet, tops.

I lay out on the granite slabs getting sunburned, pinker and pinker all the time—the redhead’s fantasy that maybe, just maybe, this’ll be the year I get tan. Some local folks shotgunned malt liquors and started talking loudly about Bay Area whitebread yuppies running around the day before, thinking they were ballsy jumping off rocks. I took off my little round glasses.

A pockmarked old biker in a black leather vest and blunttoed motorcycle boots threw a full can of beer into the blackberry bramble. Two men with turtle tattoos and long black hair took off their sneakers and T-shirts, but not their Levis. The older—probably in his forties—had two deep circular scars on his belly and a braided ponytail. The other, no more than twenty-five, had predatory blue eyes and a dark olive tan. They ran across the hot slabs to the shallow end of the pool while two women in matching terry-cloth tube tops—one pink and one blue—popped open Budweisers and leaned forward to watch. The men picked around in the shallows, turning over rocks for a while until they found what they wanted. Each picked up a chunk of granite about the size of a human head and then they started walking into the deep water side by side.

Everyone on the rocks leaned over to watch through the clear water. Walking upriver into the pool, the two men picked their way carefully across the bottom. Soon their chests were submerged, then their necks. They looked at each other a last time and took a deep breath before going under. As they sank below the surface their figures warped with the ripples above. A highway patrolman slowed as he crossed the bridge. The old biker took up a collection for beers and walked off toward the road.

“Crazy Indians, huh?” said the woman in blue. She lay back on her towel in the sun.

“Are these guys real Indians?” asked the other. “Indians hate water.”

One of the men appeared to have fallen a step behind the other, and a few bubbles burst above him. A cloud shadowed the pool, and for a moment the men were hard to discern from the reflected hillside. Then the sun hit the water again and a cloud of bubbles exploded to the surface; one had stopped walking altogether. The woman in pink flashed a confused look at me, then back at the water.

With a splash the younger man burst up coughing and spitting. As he swam to the rocks, the older man walked out the other end of the pool. Only when he was standing dry on a boulder did he drop his rock. I gave up on the tan and sat under a bay tree, trying to remember bluegrass songs I’d played with my dad—“Black Mountain Rag,” “Cripple Creek,” “Old Joe Clark.” He’d played banjo in a backyard country band for years and taught me to swap melodies with him on guitar. At the opening chorus of “Billy the Kid,” the one about how at the age of twelve years Billy killed his first man, the old pockmarked biker looked straight at me and said, “Hell. That’s my music. You keep playing that shit.”

When the crowd thinned out I drove off to a deli and picked up a rib-eye steak and a six-pack of rightly named Plank Road beer. The petrified mesquite in my little hibachi took forever to get hot, so I had nothing to do in that slow foothills sunset except throw gravel at bats and think about climbing. Not just peak-bagging this time either, but actually roping up. A handful of pebbles into a lodgepole pine sent clouds of fluttering shadows into the sky. A few bats dodged close like giant squeaking houseflies.

4

Just before dawn I bolted upright in my sleeping bag, sweating from the heat that rose out of the Central Valley. I thought I’d heard something nearby, maybe a coyote, so I sat for a while, smelling the dust and pine and the faint residual exhaust coming off the road. A Sysco restaurant supply truck blew past toward Yosemite and I decided to get up. I thought again about my girlfriend and how I’d begged her to come out here with me after school, maybe drift around in the truck together for a while. Go down to Mexico and space out on some beach. No interest.

In Groveland I stopped at a coffee shop with a blue-tiled floor for a waffle with ice cream and a side of bacon. At a big, round table, a man in new blue jeans and a clean white T-shirt, with a huge, hard belly and powerful hands, poured nonfat milk over a bowl of raisin bran. He listened to an unshaven older man in a green denim sportcoat and snakeskin boots talk about a Fourth of July fair, about how his son had paid five bucks for five sledgehammer swings at the Lincoln Continental but hadn’t busted anything.

Then, farther east into higher mountains; colder, pinescented air from still-blooming alpine meadows and evergreens replaced the arid dustiness of gallery oak forest and manzanita. An hour later, past the deep gorge of Yosemite Valley proper, the range stretched out in wide-open views to the north and south, hundreds of square miles of rocky peaks and forested valleys.

I remembered climbing the ancient winding stair to the top of Notre Dame during my junior year abroad: nothing but metropolis in all directions. At one smoggy horizon I saw another cathedral, Sacré-Coeur. The next day I took the metro out there. Again, sprawl to the horizon and I knew I couldn’t do it, I couldn’t stay. I read a used copy of Walden in Shakespeare and Company Books for a few days until I could get my tuition back in traveller’s checks. I blew the chance of a lifetime and headed for the Pyrenees. Everyone loves Paris . . . and the chance to live there?

Alpine meadows at nine thousand feet: acres of green rock-garden, a meandering river, white granite domes bubbling out of the trees and broken white peaks reaching to over twelve thousand feet. Air noticeably thinner and colder, smelling still more of pine and summer. At 8:30 a.m. I pulled off Route 120 into the parking lot of the Tuolumne Meadows Grill, a white canvas building alone on the mountain highway. Four skinny guys in worn-out Patagonia jackets stood around playing Hackey Sack; their white cotton pants were shredded in places, reinforced in others. I wondered if they lived here year-round—they seemed adapted, as if they’d never thought of going anywhere else and had wasted no time getting here. A man and a woman in matching blue Lycra tights stretched their hamstrings in a patch of grass. A bleach-blond teenage boy sat in an open 1965 VW bus and ate granola from a plastic bag. Dad and Uncle Sean were drinking coffee in the sunshine at a picnic table and I could see Dad laughing as I killed the engine.

“The elevator-shaft drop,” I heard Sean saying, as I walked toward them, “puts me right in the pit on this wave my buddy’s too spooked to touch, so I’m ripping down the line at forty-five, pissing my trunks”—with one forearm he made the shape of a wave with the hand curling above while the other hand motioned along the side of it—“fully spooked the monster lip’s going to close out and punish me, so I freak and bail off my board. Well . . .” He looked up at me and motioned with a finger to let him finish the story. “Well, on a fifteen-foot wave you