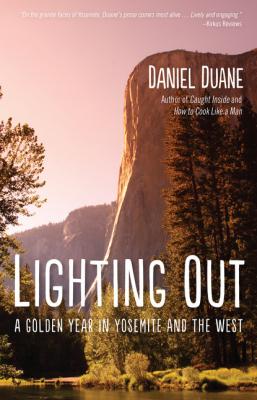

Lighting Out. Daniel Duane

Читать онлайн.| Название | Lighting Out |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Daniel Duane |

| Жанр | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781594859229 |

“I’ve been to California,” Drew said. His head so outscaled the rest of his body that the whole black-turtlenecked arrangement tottered forward under the weight of his ivory jaw. “Yeah, my freshman-year roommate’s place in Marin County. One of these BMW Deadheads with serious wealth in the woods and constant fresh-squeezed OJ. No poor people anywhere.”

The gaunt poetry editor smirked and fingered his ponytail. Visions of Vineland, of hot-tubbing Aquarians—indelible and unassailable; I’d put some of these ideas in their heads with my talk of hot springs in the high mountains and pot plantations in redwood country. Places I wanted to get back to, or hadn’t had enough of in the first place. A nativity I’d never fully acquired. The art editor, son of New York rural hippies, enormously muscular and wearing old army pants and a Tibetan vest, looked hopefully at me for a rebuttal. My vision of California had appealed to him, maybe a place to go after school. I looked out the window to where his battered blue-plaid VW bus was parked in the rain.

“Guy insisted on hiking clear to the top of Mount Tamalpais every night,” Drew continued. “Pretty smashing sunsets looking way out to sea, and it’s supposed to be some great power spot.” Drew waved around a cigarette as he spoke, dropping ashes on the table and staining his slender fingers yellow. “He swore some beatnik poets went out there in the late fifties and marched around blowing on conch shells and chanting sutras or mantras or something, so locals think the place is sacred.” I coughed a little from the smoke as my own version of Mount Tam came to mind—from Berkeley, it was a black-etched peak north of the Golden Gate lit by a burning aura from a late summer sunset. “After a week out there,” Drew said, “I was changing into somebody I didn’t want to be.”

The debate was my fault to begin with—playing the stage Californian when I’d failed at being Ivy League. The poetry editor looked evenly at Drew and me, weighing. A charismatic and emaciated neo-Marxist with a penchant for the occult, he’d grown up in Toronto and spent his summers acting in London. He loathed Ithaca’s provincialism and preferred the darkness of European cities—“shit” was happening there, changing, cops with submachine guns hung out at street corners. Sure, he’d been to a few sweat lodges with the local Black Turtle Indian Nation, but four years of hearing from me about the nature/culture split and the pristine beaches of Point Reyes had eroded his sympathy. I think my girlfriend had felt the same.

So I said I knew people in California who went to work every day and came home and paid bills and made love and got pissed at each other and it all seemed pretty real last time I was home. “It’s just that when you’re in a lovely place,” I insisted, knowing it sounded ridiculous to the whole editorial board, “it changes how you think. Maybe just a little bit, but it does. Like photo-deprivation depression. Or old doctors sending you to the south of France for cures.”

The sutras on Mount Tam even sounded all right to me—we’re a young culture, got to start sacralizing somewhere. My own honors thesis had been on the poetry of nature and place, some of it deliciously misanthropic. I’d been looking west, had ignored all the relevant scholarship and followed the advice of an old professor: “Just say no to theory.” They gave me lowest honors. Drew’s critique of the dispersed exercise of power had gotten him a summa.

“And anyway,” I said, “there’s stuff I want to do out there before I get on the career track, like learn to climb.”

“Climb?” Drew asked.

“Yeah. Rock climb. My dad’s into it.”

Drew took a long drink from his ceramic stein, then wiped his lips and smiled.

“The old WASP nostalgia for culture-free wilderness,” he said, winking at the poetry editor.

2

Thinking how to light out and where to light out for, I wandered the crowds of Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue trying to see lives, jobs, spiritually survivable careers. Twenty-one years of “occupation: student” over. I stood in front of Blondie’s Pizza, the smell of pepperoni overpowering sandalwood incense and car exhaust, and listened to a bearded man in a pink lace dress shout down a sidewalk evangelist. An irritated young man in a navy blue suit walked quickly past—he clearly had a job. Indoors. Summer, and he looked pale as he carried a banana and a sandwich off to spend his thirty free minutes on the student union steps. Without the big story of school—the firm calendar and regular punctuations of grades—did one just . . . just live? I’d heard of ex-cons who couldn’t function outside the pen, of Navy Seals who rejoined weeks after discharge. I watched the young man pass, watched the calm behind his rimless glasses and looked for evidence of despair. He disappeared into the crowd and I fell down onto a bench with vertigo.

On my way to the airport in Ithaca I’d seen one of my old pledge brothers walking across the quad. As house president he’d acquired a swagger, but that morning it was different:

“Herb,” I’d asked, “why do you look saddle sore? You know, walking bowlegged?”

“Oh, hey Opie,” he’d said, “yeah, I got that job as a trader for Salomon Brothers and, ah . . .”—he spread both hands deep beneath his crotch like he was holding watermelons—“my ’nads are so big I can barely walk.”

Mom said I ought to relax for a year, live at home and let the next step emerge. But that morning I’d found myself sitting in the same old house I grew up in while humanity was off at work. When I caught myself reading in the paper about a local water ordinance and a double suicide, my whole neck and chest constricted. I’d hustled out to sit in a café, but just got more and more wired without finishing my book. Even the summer riots had been a letdown: a homeless march martyring the guy killed in the ’69 Free Speech Riots had turned into a looting frenzy by students, gangsters, homeless people and teenage skinheads who thought it was their Vietnam. News of an impending apocalypse, but bringing no particular story to an end.

Drinking a double espresso at a green slate and black iron table, I had waking nightmares of disappearing into a hermetically sealed office building all day, coming home at night; it was easy to give fraternity guys at school a hard time for selling out, for getting jobs on Wall Street making eighty grand a year at a hundred hours a week when work for me still meant reading Ulysses. But now? What to do? Everything lucrative went on behind airtight windows. Guys twenty-one years old wore the same suits as the broken-down old-timers, both letting careers eat the whole middle out of their lives. I’d passed a gym window that morning full of people on stationary bicycles and wondered what was so awful about motion, how they could stand to resist it.

The star of our high school plays and designated hallucination tripmaster was already in Israel on a kibbutz. No plans to return to Babylon. Two of my best friends had left for Prague, the Paris of the nineties; another tired old city, but at least they’d taken off. One was shooting black-and-white photos of change, the other said he just wanted to ruminate on his pain, maybe open a used bookstore. Nick Cohen, my only friend equally interested in wasting time in the mountains, wouldn’t be back from college for another week. Aaron Lehrman, the one hardcore mountaineer I knew, wasn’t around either. Aaron’s dad, an embittered local flamenco guitar teacher, said Aaron had dropped out of artsy Reed College and hadn’t called in a few weeks. Aaron’s mom, poetry editor of a Berkeley neighborhood newspaper, thought he was somewhere out in the Rockies. I had to get out of town fast, try to get roofing work in Lake Tahoe for the summer. Winter in Jackson Hole, work at a ski resort. Maybe save up and go to Nepal, wander through the mountain kingdom like my dad’s youngest brother, Sean, had done at my age. There was a picture of him on our living room wall, an unpleasant fierceness in his eyes as he stood bearded in a blue down jacket beneath Shivling, the sacred penis of the mountain god.

I drank the last of my cold, bitter coffee and tried to imagine the fabric of an office-bound day, the actual hours spent behind a desk reading in tedium, deferring gratification. Granted, an old complaint about the rat race, but so quickly it could add up to a life lived. Stopping at my table for just a moment with a decaf latte to go, a childhood friend insisted he was at peace with going to law school. Already dressing middle-aged, apparently leapfrogging his twenties with pleasure, he looked forward