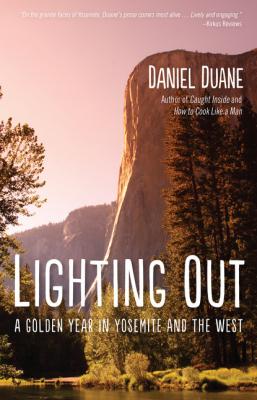

Lighting Out. Daniel Duane

Читать онлайн.| Название | Lighting Out |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Daniel Duane |

| Жанр | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781594859229 |

“You know anything about hypothermia?”

“Just that you start feeling tired and wonderful right before you die.”

“Guess it’s you and me, then, huh?”

“What?”

“Spoons. You know . . .”

Nick shook his head and peered at his hands in the dark. Then said, “Better to be homosocial than dead, eh?”

“Much.”

After a few minutes of getting used to the idea, he turned around and lay down in the dirt. I pressed my chest against his back, my legs against the backs of his. I felt him shiver. Half-asleep I hallucinated of rescues, of smiling competent men calling to me from a few yards away. A storm—or even a cold snap—would have killed us very quickly. I started awake once, hyperventilating and shaking, and noticed that a huge swath of stars was missing from the sky. Through the tree branches I could make out another amorphous vacant patch over the Cathedral Group. A colder breeze sifted through the still warm valley air and a few leaves rustled.

I pressed myself closer to Nick’s back and felt him shake from his stomach outward. He had wrapped one of the ropes around his upper body and had his cotton cap pulled low down over his ears. The flat tapping sound of light rain brushed across the tree and onto the wall nearby. I heard Nick say something.

“Hm?” I asked.

“I said this is bullshit.”

I could have sworn there was a hint of accusation in his voice. Another patter came harder and a cold drop made it through the leaves onto my arm.

In the shadowless light before dawn I woke up, surprised to find I’d slept. Nick was wide awake and shaking all over. The whole sky was overcast and the cloud cover seemed to be lowering. When I sat up he looked at me for a moment, then asked sheepishly if we could go down now. The first three rappels (sliding down ropes hung from an anchor) to the last ledge—still a hundred feet off the ground—went quickly. We were both surprised by how much technique we’d picked up.

“If the sky dumps on us,” I said, “we’re screwed.”

“You’re right,” Nick responded. “Once again, Dan’s correct.” Nick finally touched down on the ground and hooted up that he was off the rope. My bicep cramped as I pulled the rope into my rappel device. I had to stop for a moment to stretch it out—useless, untrained, collegiate muscles. I was leaning backward off the ledge when I noticed a dark curtain of rain moving down the valley toward us. Just as I swung back under the big overhang the curtain hit and I was soaked and shivering in seconds. The wall instantly became a light waterfall; my feet slipped against the rock and the rope became slick and hard to hang on to. Dirt and water poured over my braking fist and down my limbs. My T-shirt clung cold against my back while a wind blew me to one side.

Then I was down. My feet were on talus and I was shaking in big convulsions. Water squirted out the lace-holes of my suede climbing shoes. Nick helped me get free of the rope then pulled it down from the anchor. I clipped all the scattered gear onto my harness and chest rack while Nick wrapped the ropes in a mess of knots and coils around his shoulders. We ran stiffly through the forest back to the car. Inside, finally warming up, we drove over to Yosemite’s grand Ahwahnee Hotel where Queen Elizabeth once stayed. Feeling a little stupid, we walked under the massive redwood beams of the vaulted hall and past leather couches and cozy fires. Still filthy and freaked out, we stepped into the formal dining room and grabbed a couple of mimosas. Then we loaded green china plates with smoked trout at the all-you-can-eat buffet. At a steam table of eggs Benedict, Nick stopped and looked at me, suddenly exasperated.

“You enjoyed that,” he said.

“I don’t know.”

“There’s something very, very wrong with that.”

11

Plumb out of yang, no desire to get to the top of anything, I mulled over how to break it to Nick. Over a plate of bad French toast at the Yosemite cafeteria, I remembered Kyla’d be back from the music festival by now, converted or not.

“Dan,” he said, before I could open my mouth, “I can’t do it. I’m just not in the right space to climb.” We were in the car and on the road back home with more coffee, and Nick was rubbing the muscles of his neck with both hands and talking about how much the storm had shaken him. Really gotten under his skin. The confession came pouring out; he needed me to know he wasn’t like me, whatever that meant. He didn’t get off on death. “I mean,” he said, “I gotta think this through some more. Be a shame to die just to impress my mom.”

We passed the park entrance where a row of cars a half-mile long waited to pay entrance fees. Enormous RVs with names like High Plains Drifter and Footloose had canoes strapped to their roofs and Suzuki 4x4s in tow. Nick took off his glasses, breathed on a lens, wrapped his shirt around it and started kneading with his fingers. He told me he’d enrolled in a figure painting class at the university. I crassly asked if the nude models had anything to do with it.

“You do have the mind of a five-year-old after all,” he responded. “But frankly, the teacher, this French lady, is unbelievable.” He put his foot out the window in the breeze and I wished I could do the same. “My mother’s not going to believe it,” he said. “She hates it when I change obsessions too quickly.”

12

After a long, meandering drive out to Point Reyes, carasick from apple-strawberry juice and fig bars, Kyla and I parked in an empty dirt lot near a dairy farm. We put on warm clothes and walked out through sheep and cattle pasture toward the fogbound beach of Abbotts Lagoon. I rambled for a while about my epic with Nick and how he’d apparently had some kind of mental break over the whole subject, but I couldn’t quite find the right tenor for the story—was I thrilled by the danger? Exaggerating it to impress her? Contemptuous of Nick or supportive? She didn’t seem sure on any count, and I realized I wasn’t either. So I asked about the women’s music festival. Tried to keep my voice neutral, not sound mercenary.

“Overwhelming,” she said. She pulled her arms into the body of her thick fisherman’s sweater and let the sleeves swing around as she walked.

“How? In a bad way?”

“Yeah . . . sort of.” She looked at me with wide eyes. “I thought it’d be different with women. Not such a pickup scene, but it was totally the same.” She got an arm free and pointed suddenly—an egret stood in the reeds of the lagoon like a white flamingo in a northern garden. Its long neck arched with an elegance contrived and almost un-Darwinian. Friends had warned her that the Yosemite Festival was notorious, that it probably wasn’t the best place to look into being with women.

“Look,” she said, sounding very frank, “the whole thing with me wanting to be with women was just that men weren’t making me happy. Or not the ones I’d been with, anyway. I’ve had fun sex with men, but only a couple of times.”

And where does that leave me, I wondered. Sure, like most guys I secretly fancied myself an artful, healing lover, but this could be quite a burden. Men, she said, just never bothered to find out what felt good for her; her mind usually wandered to phone bills or to imagining what her body would look like from above. She poured wet sand into circles as she talked. A leather thong around her ankle was encrusted with salt from walking in the surf.

“I’d really decided not to be with men at all anymore,” she said. “You should know that.”

The past-perfect verb tense was a tip-off . . . she was open to a change of mind. She drew a finger along the lovely downy hair above her lip. Again I wanted to kiss her, to just get past this nutty talk. I mean, here we were! On a deserted beach! But instead, I said, “Why should I know that?”

She took my left hand and held it for a moment. She started to pick at the scab of a climbing cut, then leaned forward in the sand