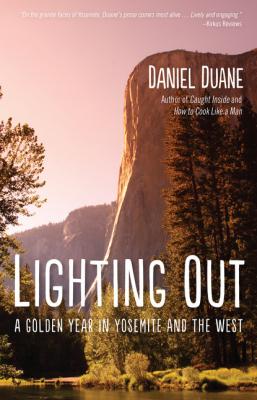

Lighting Out. Daniel Duane

Читать онлайн.| Название | Lighting Out |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Daniel Duane |

| Жанр | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781594859229 |

Dad pulled me down next to him at the picnic table and put his heavy arm around my shoulders. His hands were covered with athletic tape and scabs and his hazel eyes were alive and calm like they never were in town. He and his brother were both darker-skinned than I was and both had dark brown hair, but Dad was balding and he was shorter and thicker than Sean. Sean was my height—almost six-foot-three—and had more angular features and a broad, thin-lipped smile over perfect teeth. He took a sip of coffee, then went on. “So twenty thousand gallons slam me toward the reef but for some amazing reason my back slams down against the only patch of sand in the bay. I was like, ‘sheeeeeit, this place ain’t shit.’ Hey, Danny! You look a little pale, you got the flu, or what?”

They were up training in the Meadows to climb the Northwest Face of Half Dome—the ultimate aspiration of their shared alternate life. Three full days on a wall, sleeping on ledges, climbing from dawn to dusk. They’d been working up to it the whole time I’d been in college and were finally ready. They’d gone through a long series of practice climbs, a program of steps and trials. Dad got some more eggs on a paper plate and they talked about how ready and how scared they both actually were. It was an enormous, world-famous wall, maybe just enormous enough to ease the frustrations of their urban lives.

Sean had come up for the climb from San Diego, where he and his wife lived by the beach. At forty he was surfing three times a week, running ten miles a day and, at his wife’s insistence, seeing a therapist about his Peter Pan complex. He’d been enjoying selling wine for two California wineries—driving up and down the state, skiing in Tahoe when he made winter sales trips to the resorts, climbing in the Meadows when he had to come up to Mammoth in the summer. Sean had also patiently taught me how to surf when I was a kid. We’d camped out in his little car in a parking lot by a nuclear power plant at San Onofre and he spent a whole day showing me how to spring to my feet. It took a while to stick, though, because up north where I lived it was more about character-building than fun-in-the-sun: fogbound rocky coastline with pounding Pacific waves, frigid water. He said it’d be a soul-surfing experience up there if I could ever get good enough for the bigger winter swells. Fewer kooks in the water, fewer Nazis.

5

At sparkling Tenaya Lake, Dad, Sean and I walked up shinaing slabs to Stately Pleasure Dome. Dad walked evenly, with his head down, placing his feet carefully as the rock steepened. He wore blue canvas shorts and a red T-shirt and had an old blue rope coiled around his shoulder. My little day pack was crammed with all this great stuff that Dad stored on hooks out in the garage: rock-climbing shoes, a sit-harness, a bag of gymnastic chalk to keep the hands dry of sweat, thirty or forty snap-link carabiners, little metal wedges on cable loops for sticking in cracks in the rock—called chocks, nuts or stoppers, contraptions called “Friends” with four quarter-circle cams—when you pulled a trigger the cams pulled back, when you released it they expanded into a crack.

Dad strapped me into this elaborate nylon harness and made me watch him do the buckle—apparently if you blew it, the thing could dump you. Sean went straight to work, muttering to himself while he organized the rest of the gear. It seemed like he had some routine he was running through, some whole program he and Dad had worked out.

“While I climb,” Dad said, pulling a little white cap over his bald spot, “. . . you listening? While I climb, Sean feeds me rope, OK? And if I peel off, Sean’s got this brake so it stops feeding. That’s my whole life right there in that guy’s hand.”

“Come on, man . . . get going,” Sean said. He looked over at me in annoyance, sick of the first child’s thoroughness.

Dad tied into the rope and led off up the wall. At more than twice my age, he was in way better shape. While he climbed, the rope trailing from his harness down to Sean, I watched him put chocks in little cracks in the rock. He’d clip a carabiner to the chock, then clip the rope below him through the carabiner. I got to wondering just how badly I actually wanted to do this. The stakes seemed pretty high. Back down at the lake a couple of kids were floating around in inner tubes.

“Guy’s tenacious,” Sean said. “Yesterday he kept blowing off this overhang, bleeding and yanking me all over the place. But he kept at it. I would’ve been out of there.” I tried to imagine Dad dangling upside down by his fingers, tried to gauge the truth-content of the remark; it was certainly possible.

Dad did most of the work on this route with his feet, just kind of walking up the rock.

“All right,” Sean said, “your turn, Danny. How do those rock shoes feel?”

“Horrible.” They were mashing my curled up toes together and the seams were excavating trenches on the tops of my feet.

“How bad?”

“Really horrible. Like, I may never walk again.”

Sean laughed, enjoying his hardman posture. “Then they’re way too loose,” he said. “No kidding. And take my chalk bag.”

“You think I’ll need it?”

“I don’t know, you’re so scared already your palms are dripping. You don’t want to grease off, do you?”

Not at all. Nope. Not even a little bit. I clipped the bag onto my harness and shoved both hands in there. White courage.

As I climbed, just kind of walking upwards, focused like a madman, my knees shaking, Sean yelled, “Keep breathing! Don’t stop breathing!” Astonishing that Dad got a kick out of this, not to mention it being irresponsible for a man with children. Dad grabbed my hand when I got close and hauled me in, then immediately attached my harness to the anchor he’d built. Sean climbed after us, pulling up with long swimmer’s arms.

They fumbled with equipment and knots for a while, getting ready for the next “pitch”—the next rope-length of climbing. I remembered that Dad had learned the rope system from an eccentric old climber in Berkeley who was quasi-religious about safety. As the bright blue day wore on, and I watched these two brothers work together, I could tell safety had become a discipline of its own for Dad—knots always backed up, carabiner gates always down and away from the rock, double ’biners opposed and reversed, ropes well coiled and neat—a litany of details, of logical checks and balances.

At a little ledge up there in the cool mountain wind and thin-atmosphere sunshine, Dad talked me through every step in the chain of self-protection. He laid out rules with moral intensity: never clip like this, always like this; absolutely never commit to two pieces of protection, always three; never, ever unclip from an anchor when you’re not on belay; never let anyone unclip you; always look over an anchor, no matter who’s built it. The system made sense and I imagined if you stayed manic about it, climbing could be survivable. I pictured all the long days Dad had spent moving over stone far away from his job and life, engaged in a system rhythmic enough for his usually constricted, uneven breathing to follow suit, absorbed in the running of ropes, the tying of knots, the fitting of steel into stone.

Near the top I got confused as to where to move and had to dip my hands a few times in the chalk. I couldn’t see anything to hold on to or any particular place to put my feet. My stomach knotted up, and I looked around for what hold Dad had used. The gray-and-white rock was speckled with mica and feldspar. Sections were polished by glaciers to the smoothness of glass; they reflected the sun like the mirrors sewn on one of my old girlfriend’s fraternity date-night dresses.

“Trust the shoes,” Sean said, like telling me to use the force. “They’ll stick.”

He was right—the rubber held better than sneakers on pavement, and after a few steps my eyes wandered away from the granite around me. That huge, wild white dome up in the sky dropped gently back down to the banks of blue Tenaya Lake; above, it curved away into an equally blue horizon. To either side, more walls of this pure, clean, pale stone lay against the air—the raw stuff of the High Sierra, stark and clean, and I was wandering around on it with my dad and uncle and with nowhere to be but right there. And so terrified I couldn’t help but focus; I hadn’t thought about much but a rock in over an hour.

When