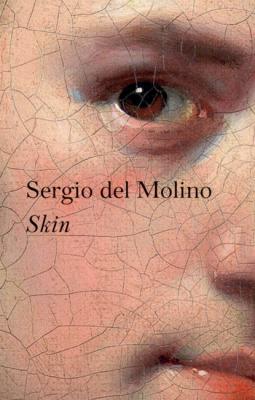

Skin. Sergio del Molino

Читать онлайн.| Название | Skin |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Sergio del Molino |

| Жанр | Социология |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Социология |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781509547876 |

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4787-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021938631

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

‘Everything would be fine, if it weren’t for the damned skin.’

Vladimir Nabokov

Witches Don’t Egg-siss

Have you got it now, how to recognise a witch? We’ve read Roald Dahl’s book enough times. Let’s go through what he said again … They’ve got blue saliva, but that doesn’t matter because they’re careful to avoid spitting, so that nobody sees what colour it is. Shoes are always uncomfortable for them, which is because they don’t have any toes – no make ever fits them. You can also check to see how wide their nostrils are, or look in their eyes, which have a reflection in them of a fire or the sky, but these details can be misleading; you get women with strange eyes and big noses who aren’t witches. Because a witch, remember, is not a woman. She looks like a woman but she’s something else altogether, in the same way that a vampire is not a man, he only looks like one. The best way to spot them is by the gloves and the hair. They’re bald, and the wigs they wear irritate their scalps, giving them patches of eczema; it’s known as wig eczema, and it means they’re forever scratching. And they always wear gloves, even inside the house. The gloves are to hide their nails, which, at the tips of their long, red hands, are shaped like claws. Have you got it now? Would you recognise a witch if you passed one in the street?

Dad, I’ve told you a thousand times, witches don’t egg-siss.

He is seven years old and still can’t pronounce ‘exist’ properly. He splits it into two, and cannot form the final ‘t’. So: ‘egg-siss’. I never correct him, and I don’t know if I ought to. All parents fall in love with their children’s speech defects. Even to the most hysterical parents, those who avail themselves of speech therapists, every advance in language feels like an amputation. The way he splits ‘egg’ and ‘siss’ is down to a tiny, subtle hook on his palate, one that not even he perceives but that keeps him attached to my body. I let him say ‘egg-siss’ even though I know he will soon be saying ‘exist’, moving that little bit further away from me when he does.

Of course they exist, I tell him – pronouncing ‘exist’ correctly so that he doesn’t suspect I’m making fun of him, or even that I find his pronunciation funny. How do you know they don’t exist?

Because they don’t, just like ghosts don’t, or werewolves, or vampires.

Whoa there, nobody can deny there are werewolves. Remember last year in Galicia, when you heard that one howling?

That could have been the wind.

The wind, you say.

It was summer time, we were staying in a small house next to an area of rocky scrubland and had spent several weeks talking to him about how to defend against the local versions of witches – las meigas – and about how the spirits around there went and sheltered by the nearest stone cross, and how to interpret the strings of lights that sometimes became visible from the hillside. All to no avail.

They don’t egg-siss, he told us.

Then why do they build so many stone crosses?, we asked.

Because Galicians believe in these things, he replied, slightly condescendingly, slightly xenophobically too.

There was a full moon that night, and I decided to do an imitation of a howl.

Cut it out, Dad, he said.

Cut what out? I said. I didn’t do anything.

At that he fell silent, clearly petrified.

What? I said. Did you hear something?

No, he said. Nothing, it must have been the wind.

So you didn’t hear a werewolf, then?

Werewolves don’t egg-siss, it was the wind.

But he squeezed my hand very hard, and picked up the pace.

His mother and I smiled at each other. At last, a chink of terror, something inexplicable breaking through into his world of soft, cuddly certainties. It’s of the utmost importance that children find forests terrifying, and it’s down to the parents to nurture that fear, even if only so that they come running to us for protection.

With witches, I’ve never had the good luck I had that summer night in Galicia. However many times we run through the tell-tale signs and however many times we read the Roald Dahl book or watch the film with Anjelica Huston as Grand High Witch, there’s simply no way to make the walls of fiction come tumbling down. The boy goes to sleep entirely unafraid of witches coming and rapping their knuckles on his window after the light goes out.

Every night when I come out of his bedroom, I leave the door ajar and the kitchen light on. Not to banish a fear of the dark which he does not feel, but because he doesn’t like the sensation of being separate from us. He knows that, after the good-night kiss, his father embarks on another life that does not include him, and leaving the door open is a way to remind me that he exists. He does, witches do not.

Night night, let me know if any witches come in the room.

Witches don’t egg-siss!

In the hall, before I get to the living room, I start scratching myself. My arms, my back, my hair. There are times when my scalp itches as though I’ve got witches’ eczema. If my nails are long, I draw blood, marking my shirt, the upholstery and the bedsheets, these droplets revealing – like those at a crime scene – my true nature, which I have kept hidden all day and which, sitting alone in the armchair, eating some unexciting supper while watching whatever happens to be on TV, I uncover and allow to suppurate. My true self, with neither long-sleeved shirts nor shoes on. I cannot tell the full moon from the new, and neither do I go looking for prey to satisfy my homicidal appetite. Like all true monsters, I’m a threat to nobody. I only seek refuge from a world that would come after me with burning torches and pitchforks if it saw me as I am.

Not even my son can be allowed to see me. Although he senses me. If our children found us out, we would run the risk of them accepting us as monsters, and that would be fatal – for them. This is why I leave the door ajar and not wide open, so that he isn’t