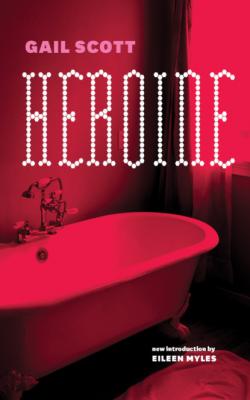

Heroine. Gail Scott

Читать онлайн.| Название | Heroine |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Gail Scott |

| Жанр | Современная зарубежная литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Современная зарубежная литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781770566064 |

the tongue of your sandal

between my toes

glides through the grass in the orange grove

there has been a communist purge

a dead scorpion lies upturned

on the road to the fortress

Then we were heading northeast across the desert. After a day and a half, the train rolled into flowered vineyards, then the city of Algiers. In a lighted square, a white-clothed man with a thin dog leaned back, playing his flute to lions of stone. Stepping off the train, a plainclothes cop arrested us. It was midnight. He led us out under the Arabian arches of the station. Saying it was for our own protection. Because the streets at night are dangerous. ‘God,’ I thought, ‘somehow they’re on to the fact we’re into heavy politics back in Montréal. What if they find the poem with the word ‘communist’ in my purse? Now I’ve really blown it.’

The police station was plastered with pictures of missing children. Beautiful girls and boys of all ages. Probably sold to prostitution. That’s racist. They let us spread our sleeping bags in the same cell. When in the morning they said: ‘You can go now,’ my love, I was so relieved it seemed that anything was possible. So at a fish supper in a fort restaurant on the middle corniche where Algerian freedom fighters had daringly resisted the French, I said: ‘You’re right to be against monogamy. As long as we trust each other anything’s okay.’ Through the open window I saw a beautiful brown man, naked from the chest up. He was looking in, holding a fish net. As if he’d emerged from the sea. ‘Anyway,’ I added, ‘the couple is death for women.’ You smiled with your wonderful soft lips. We headed north. In the mirror of a hotel room in Hamburg, you took a self-portrait.

Everything was perfect.

Except, at Ingmar’s, your mother’s boyfriend’s winter house on the Baltic, something started going wrong. That particular morning, I must have been dreaming. Because lying back I saw a face looking through a window, smiling. Vines around its neck. Glistening as though it had risen from the sea. Only, outside a slow brown river ran. It was the city. Pink lights on tall white buildings. Red and yellow streets. I woke up to a winter morning. Shadows of noir et blanc. Smell of coffee in a china cup. Bluish tile cooker reaching to the ceiling, Northern European style. Yes, everything was perfect. So why at that precise moment did I get up, open the cooker’s little brass door, and throw the photos of your former lovers in the fire? Just as you came in.

Your silence left me confused. All that European retinue across the winter room. Then the Modigliani print on the wall behind the golden strands of your hair reminded me I needed a man like you to learn of politics and culture. I’d have to try harder. Thank God, despite my error, our days continued to be wonderful. Walking white streets eating almond-cream buns. The falling snow giving an air of harmony. Yet under that blanket of perfection (we were a beautiful couple, everybody said so) the warmth seemed threatened. As if I couldn’t handle the happiness. Secretly the darkness of the closet beckoned. I wanted to sink down among the silence of your coats. (Good wool lasts forever.) Your mother, turning her head from a conversation with her son, said to me: ‘À quoi ressemble ta famille?’ I saw the smokestacks of Sudbury. And her emaciated face sitting on the veranda. ‘Fine,’ I answered, smiling broadly as if I didn’t understand the question.

The feminist nemesis was that the more I felt your love the harder it was to breathe. In Hamburg, when the subway stopped between two stations and the lights went out, I began to sweat. Pins and needles pricked my chest so much I wanted to grab your sleeve and say: ‘Help, please.’ But hysteria is not suitable in a revolutionary woman. Thank God a winter-shocked unemployed Syrian immigrant started to bark. His family gathered round him laughing nervously. Eyeing back the fishy stares of other passengers as if it were a joke. As if it were a joke. My fear of crowds at demonstrations was harder to conceal. Although you’d have been initially forgiving. Because paranoia in new politicos is normal. Given how scary it is to become conscious of the way the system really works. Anyway, following that little blow-up at Gdansk, when we went to a local march in solidarity, I heard the press of soldiers’ feet behind us. Someone yelled: ‘To the church, to the church!’ My love, the crowd was barreling down so heavily that when they closed the huge oak door I was out and you were in. How could you have let it happen? How?

It wasn’t the right question.

The peace in a foreign place was visiting your grandmother. Behind the winter-spring light she stood in her embroidered apron. I said: ‘Hers is the last generation before occidental cultural homogenization, dominated by America.’ You looked up, interested. Just then your cousin came into the room. Behind her glasses I detected an infinite sadness. ‘Gertrude’s dead,’ she said. ‘We think she killed herself because of Lenz. He was having an affair.’

I quickly checked the woman in the mirror over the mantel. She had straight bangs and a well-cut raincoat. It couldn’t happen to her. Although I’d have to play it careful now, given how weird I felt. The trick was to sit straight in my chair (like a European woman), carefully modulating my voice when we disagreed so as not to sound aggressive. You hated a lack of harmony. Unfortunately, my old self-conscious laugh came creeping back. Especially after your high-school girlfriend came for a visit. Watching the two of you dance over the Marienbad squares, with her head in that safe place under your chin, I felt like screaming.

Suddenly you grew cooler. Wound up as I was, I didn’t see at once that I was spoiling things by trying too hard. Not until I read about the German guy they wrote of in the paper. He wanted a driver’s licence more than anything in the world. Due to the fact he’d stayed home on the farm to take care of the folks and needed a way out. Just to make sure he wouldn’t fail, he practised in the backfield for several years. Then he passed the test without a hitch. The tragedy was that driving home down a country road he hit a girl. In the dark and pouring rain she seemed dead, so he buried her in the streambed. Incriminating evidence must stay below the surface. After that he tried harder when he hit another, backing up and having several other goes, before sending her, also, to her final repose in the sand under the little river.

I’ve got to get control. Lying with my legs up I see the whole picture in my head. As infinite as unsullied snow. Then a man walks over it dragging an iron-runnered sled. The hard knocks of realism. The dark arpeggios on the radio blend with the sirens outside. Janis is singing that if you love someone so precious their beauty cannot be had completely. If someone comes I’ll turn it off. So no one can say: ‘You’re stuck in the past. In his photos of Morocco; in his images of love.’

That’s what Marie said once. Her exact words were: ‘Il faut choisir. Car une obsession, c’est l’hésitation au point d’une bifurcation.’ We were sitting in Figaro’s Café, circa 1977, looking at a picture of your other woman. My alabaster cheek against her olive one.

The unfortunate thing is, Janis just happened to come on the air this afternoon when Marie was here. Singing ‘Piece of My Heart’ (Take it! Take it!) Reinforcing the impression I was still living in my own soap opera. With an irritated rattle of her silver Cartier bracelets, Marie reached over and turned it down. Through the partly open bathroom door, I watched to make sure her Grecian profile didn’t look toward me and say: ‘Pour moi ta vie prend les airs d’une tragédie.’

She already said that once. A beautiful summer evening, and I’d just come up the sidewalk in my red flowered skirt. Holding out some sparkling cider and a rose for her. She, standing in the doorway, said, smiling: ‘Tu as les petits yeux pétillants, pétillants, pétillants.’ Then her face darkened and she showed me a scientific astrological analysis of how women with my birth date often end badly. The example was Janis, born on the same day. Dead of an overdose. I said: ‘Yeah, but she died famous.’ Sepia, what scared me was the look in Marie’s eyes. As if she knew something terrible would happen. I could only think, my love, that it was in regards to you. So I added nonchalantly: ‘Anyway, to the victor belongs the spoiler.’

I’m sorry, my love. You were a new man who tried. I just wish you hadn’t