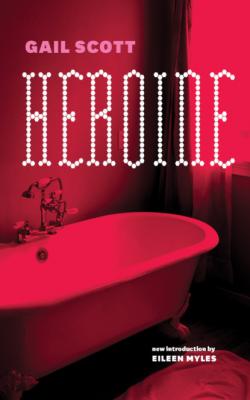

Heroine. Gail Scott

Читать онлайн.| Название | Heroine |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Gail Scott |

| Жанр | Современная зарубежная литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Современная зарубежная литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781770566064 |

A feminist (I kept repeating)

cannot be impaled

by a white prince.

The trip was like a dark tunnel. At the other end there would be light. When I got to Vancouver, I’d see, maybe, how to be free. Janis Joplin came on the radio. Her voice cracked like one of those evergreens trying to grow on the burnt earth outside Sudbury. She said: There’s no tomorrow, baby (laughing her head off). It’s all the same goddamned day. We learned that coming here on the train.

The Dream Layer

’Tis October. On the radio they’re saying ten years ago this month Québécois terrorists kidnapped the British Trade Commissioner. I was at my kitchen table. Through my window the mellow smell of autumn leaves in the alley. Making me slightly ill due to a temporary pregnancy. A drunk wove along the gravel. I was just wondering how to put it in a novel when the CBC announcer said: ‘We interrupt this program to say the FLQ has kidnapped Britain’s trade representative to Canada.’ I couldn’t help smiling. Even a WASP, if politicized, can recognize a colonizer. Besides, the crisp autumn air always made me restless. Later, my love, we laughed so hard when the tourist agent told the group from Toronto looking for cultural manifestations in Montréal: ‘Eh bien ici les manifestations ont lieu d’habitude au mois d’octobre.’ Winking at us in line behind them (we were going to Morocco). For in French manifestation also means political demonstration. He meant the October Crisis and other assorted autumn riots. People were freer then.

Alors pourquoi Marie a-t-elle dit que je ne serai pas au rendezvous? She meant on the barricades of the national struggle. Her face had this funny look, half guilty, half cruel. (She was still in the revolutionary organization then.) Even hinting that my grandfather might be Métis didn’t convince her. Of course I didn’t tell her and the other comrades the family kept it hidden. Why should I? They must have guessed anyway, because M, one of the leaders, tugged his beard and said: ‘We’re materialists. We believe one is a social product, marked by the conditions he grew up in. You’re English regardless of your blood.’ We were sitting in the revolutionary local. Around the table no one said a word. Even you, my love, I guess you wanted to keep out of it.

Marie’s face had that funny look again today when she came to visit. She was wearing an immaculate silk scarf. Over it her nose turned aside as if offended when she saw the state of my little bed-sitter. Granted, it’s kind of tacky. Green patterned linoleum and an old sofa. In the bathroom, black-and-white tiles like they have in the Colonial Steam Baths. Except some are falling off. Trying to make light of it, I said as we stepped into the room: ‘Ha ha, the hard knocks of realism.’ She didn’t laugh. She didn’t even smile ironically. So I decided to hold back. Refusing to explain how I’m using this place for an experiment of living in the present. Existing on the minimum, the better to savour every minute. For the sake of art. Soon I’ll write a novel. But first I have to figure out Janis’s saying There’s no tomorrow, it’s all the same goddamned day. It reminds me of those two guys I once overheard in a bar-salon: ‘Hey,’ said one, except in French. ‘Did you know the mayor’s dead?’ His lip twitched. ‘No kidding,’ said the other. ‘When?’ ‘Tomorrow, I think.’ They both laughed. Sure enough the next day on the radio they said the mayor was at death’s door. Nobody knew why. City Hall was mum. Rumour had it there’d been an assassination attempt by some unnamed assailant. I felt like I’d seen a ghost.

I got that same feeling again later taking a taxi along Esplanade-sur-le-parc. On my knee was the black book. The budding trees were whispering, the birds were singing: a beautiful spring eve. (Like when we first fell in love, my love.) When suddenly on the sidewalk I see a projection of my worst dreams. A real hologram. You and the green-eyed girl. Right away I notice she’s traded in her revolutionary jeans for a long flowing skirt. And her hair is streaked. Very feminine. As for you, you’re walking sideways, the better to drink her in. With your eyes. Oh God, obviously you can’t get enough. The taxi dropped me at the bar with the little cupid holding grapes in front of the mirror where I was going to meet some gay writers. One of them said: ‘Chérie, you look terrible.’ I was speechless. All I could think was what a coincidence. Because at the moment I saw you, my love, I’d been writing in the black book (not believing yet that our reconciliation was really finished): He’s Mr. Sweet these days. I’m the one who’s fucking up, making scenes. Oh well, tomorrow’s another day.

‘Qu’as-tu?’ asked Alain. He has green eyes like my father, but he wears jewellery.

I said: ‘I think I’ve seen a ghost. Real-life from a nightmare I once had. Everything back exactly as it was.’

‘Trésor,’ dit-il, ‘la science dit que la répétition n’existe pas. Les choses changent imperceptiblement de fois en fois. Maintenant tu vas prendre un bon verre.’ I didn’t reply, concentrating as I was on how to be a modern woman living in the present while at the same time finding out who lied, my love, me or you?

A delicious warm sweat is forming on the bathroom tiles. Through the open door I see the dented sofa where Marie sat this afternoon. Determined as ever with her flat stomach and her straight back. In that immaculate white silk. Suddenly she put her hand over her mouth, as titillated as a little girl who’s caught a glimpse of something unspeakable. I knew it was that place above the stove where the dirt adheres to the grease, working the paint loose until it starts to peel off. And she was about to criticize my housecleaning. To ward it off I focused on how growing up over that dépanneur in St-Henri probably made her fussy. Every Monday and Thursday after school she had to take off her blue tunic and scrub and scrub the slanting floor under the domed roof. What got her was the darkness of the courtyard. You could feel it from the kitchen window. One day, walking in there she found a big rat lounging on the table. Slowly unwinding his virile tail, he looked at the little girl with his small eyes and said: ‘Mademoiselle, voulez-vous me ficher la paix?’ In International French. She couldn’t think of a thing to say. None of the neighbours spoke like that. Later, she thought it was a dream.

Glancing only slightly in my direction, she blurted it out in spite of herself: ‘Tu pourrais faire un peu de ménage. On dirait que tu n’as plus d’amour-propre.’

I kept silent. It’s better than saying: ‘What about you? You’re too obsessed with how things look.’ Besides, as I’d decided to take a bath, I was busy with my ablutions.

I guess I lost track of time. Because I didn’t see her get up and say goodbye. I realized she hadn’t said anything about coming back.

Colder times are coming. In the telescope the plain whitens. The tourist sees a field of car wrecks below the skyscrapers. A woman is walking toward a park bench. Suddenly she sits, pulling her coat down in the front and up in the back in a single gesture so you can hardly tell she’s taking a pee.

Oh, faucet, your warm stream is linked to my smiling face. Outside the shops swing: peanuts, blintzes, Persian rugs. Marie m’a dit: ‘Tu as payé avec ton corps.’ Shhh. Reminiscences are dangerous. Who said that? Never mind. When I get out of here I’m going to throw out those old pictures on the stool by the tub. That one half-hidden in the folds of the second-hand lime-green satin nightgown must have been taken in Ingmar’s courtyard. Black and white with a silvery grey light shining on the shoulders of our dark leather jackets. We were the perfect revolutionary couple, tough yet happy. Leaning together after a walk in the Baltic fog, eating almond-cream buns. Except at Ingmar’s somebody almost stole the silver plate from me.

What went wrong wasn’t obvious. Earlier, travelling in Morocco, everything seemed perfect. The magic was in slipping out of time. No landlords, no waiting for you to phone, my love. The air was filled with spice, roast lamb, mysterious music, the delicate odour of pigeon pie. From our hotel room we heard an Arab kid with a knife offer to make a rich woman tourist high for a price. We laughed as his voice mocked her under the arch of the starry sky (’twas in life before feminism). I loved our mornings. Honey and the smell of Turkish coffee in the huge café at Poco Socco. With the passing donkeys and men in felt hats and beautiful djellabas obscuring our view of the rich American junkies on the other side,