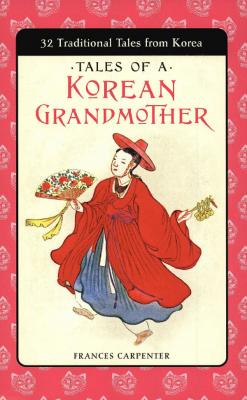

Tales of a Korean Grandmother. Frances Carpenter

Читать онлайн.| Название | Tales of a Korean Grandmother |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Frances Carpenter |

| Жанр | Учебная литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Учебная литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781462902903 |

"It was that dog who finally saved the fortunes of the old wineshop keeper," Halmoni explained. "First, he tried swimming out into the stream to look for the amber. But it was too deep for him to see the bottom. Then he sat beside the river fishermen, wishing he had a line or a net like theirs that would bring up the golden prize he sought. Suddenly from a fish that had just been pulled out of the water, the dog sniffed amber perfume. Grabbing that fish up in his mouth before the fisherman could stop him, he galloped off home.

"'Well done, Dog,' said Old Koo. 'There is only a little food left under our roof. This fish will make a good meal for you and me.' The old man cut open the fish and, to his surprise and delight, the bit of amber rolled out.

"'Now I can put my magic charm back into the jug,' Koo said to himself. 'But there must be at least a little wine in it to start the jug flowing again. While I go out to buy some, I'll just lock the amber up inside my clothes chest.'

"When Koo came back with the wine and opened the chest, he found that instead of the one suit he had stored in it, there were now two. Where his last string of cash had been, there were two strings. And he guessed that the secret of this amber charm was that it would double whatever it touched.

"With this knowledge Koo became rich beyond telling. And in the gate of his fine new house he cut a doghole for his faithful friend, who had saved him from starving. There, day and night, like our own four-footed gate guard, the fat dog lay watching in peace and well-fed contentment. But all through his life he never again killed a mouse nor made a friend of a cat."

STICKS

AND

TURNIPS!

STICKS

AND

TURNIPS!

IT WAS kimchee time once again. In the courtyard the crisp, cool autumn air was heavy with the savory smell of this good cabbage pickle, which every Korean liked so well to eat with his rice.

When each little eating table was prepared in the kitchens of the Kims and their neighbors, the main bowl upon it was heaped high with fluffy, steaming hot rice. In the other bowls ringed about this one, there might sometimes be soy sauce or bean soup, sometimes seaweed cooked in oil, sometimes dried salted fish, or even meat stew. But there was always one bowl filled with spicy kimchee.

Now, at kimchee time the courtyards of the Kims were carpeted with long, thin heads of Chinese cabbage. Westerners call this celery cabbage because of its white stalks topped with pale green. Huge piles of turnips and onions, strings of garlic and ginger, and bundles of strong salt fish also were there.

Ok Cha and the other little girls of the household tagged behind their grandmother while she supervised the women who were washing and soaking the vegetables in salt water. The children liked to peer over the rim of the great kimchee jars to see how nearly full they were. It was dark on the bottoms of the jars, a full six feet below the level of the courtyard. Like the water jars, they were sunk deep in the earth to keep them from freezing.

"Ai, take care, Ok Cha! You are not a red pepper. Nor yet a fat turnip to be mixed with the kimchee!" Halmoni cried out, seizing the rosy red skirt of the child as she almost lost her balance. She was just in time to save her from a headlong dive into the huge pottery pit.

The old woman led the little girl away to safety on the other side of the courtyard, where Yong Tu and his cousins were carving giant turnips into little round lanterns. The boys had beside them slender rods cut from the bamboo in the Garden of Green Gems. On these little sticks they hung their turnip lanterns, when they had pasted bits of kite paper over the holes dug in their sides.

The Korean grandmother was tired. She was glad to sit down on the nearest veranda step and watch her grandsons at their work.

"Sticks and turnips! Sticks and turnips!" the old woman murmured, shaking her head solemnly, but with a twinkle in her dark eyes. "Take care, my sons. Take care you don't turn someone into an ox."

"Turn someone into an ox, Halmoni?" Yong Tu asked, wondering. "How could that be? And what have sticks and turnips to do with such a strange happening?"

"It's an old tale about a farmer, blessed boy," Halmoni replied. "A farmer who took revenge on a city official who tricked him. It all happened long, long ago. Who can tell whether it really happened at all? But the tale goes like this--

"There was a farmer named Cho who had had years of good luck in his rice fields. Such good luck was his that he had many huge chests filled with long strings of cash. But like many another fortunate man, he was not content with his lot. Cho grew tired of plowing his fields and harvesting the good rice. He longed for the softer, easier life of the capital city of Seoul."

"'Now if I could only buy for myself an official's hat, I could grow even richer,' Cho said to his family. Then, as now, my children, it was always the government officials who grew rich. They handled the money the people paid in taxes into the King's treasury. Of course a good deal of that money went into their own brassbound chests. They called this their rightful 'squeeze.'

"Hué, that farmer came up to Seoul. He straightway sought out the Prime Minister to ask for a good position at the King's court. Cho made the Minister many rich presents. He went every day to the Minister's courtyard to plead his case.

"'Perhaps tomorrow,' the Minister said every time Cho laid a gift at his feet. But that tomorrow never came. One year—two years—three years—and four. Again and again, Cho sent home for more money out of his cash chests. One does not eat for nothing here in the capital.

"Then one day there came word that his cash chests were all empty. His rice fields were neglected. His house would have to be sold. His family were starving.

"'Help me to the position now, Honorable Sir,' Cho pleaded with the Minister. 'My cash chests are empty. I shall have to give up and go home.'

"But the Minister only shook his head and again said, 'Perhaps tomorrow.'

"Cho turned away from that Minister with rage in his heart. He vowed he'd get even somehow and sometime.

"On his journey home Cho took shelter one night under the grass roof of an old country couple. They made him welcome. They shared their rice and their kimchee with him. They gave him the warmest part of the floor to sleep upon. But as the sun rose and the cock crew, Cho, half-awake, heard them talking above him.

"'It is now time to take the ox to the market,' the old man said to his wife. 'Get me the halter.' And he began to tap Cho lightly all over his body with four little sticks. Cho tried to cry out, but to his surprise the only noise he could make was the bellow of an ox. When he rose from the floor, he found himself standing on all fours, and the old woman was putting a ring in his nose. As he went out of the hut, he had to take care lest his horns catch in the doorposts. The poor man had been turned into a great hairy ox.

"As he was led along the highway by the ring in his nose, Cho's heart was filled with dismay at the trick that had been played upon him. He was the finest and fattest among the many animals at the cattle market, but his owner asked such a high price that at first none could buy. Finally there came a butcher who had tarried too long in a wineshop. His senses were dull, and he paid the high price. Then he led poor Cho away to be killed.

"Fortunately for Cho, the road they took passed another wineshop. There the drunken butcher tied his prize ox to a stake, so that he might go in and have just one more bowl of sool.

"Cho himself was hungry, and thirsty, too. And just across the road from the wineshop there was a field of fine turnips. With his great strength the ox-man was able to pull the stake out of the ground and to break his way through the roadside hedge. He pulled up a juicy turnip and sank his teeth into it.

"As he munched, Cho's hairy hide began to itch. His great body began to shake. He rose up on his hind legs. When he looked down at his hands and feet, he saw to his delight that he was a man again. Cho walked out into the road,