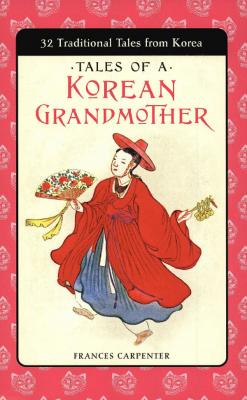

Tales of a Korean Grandmother. Frances Carpenter

Читать онлайн.| Название | Tales of a Korean Grandmother |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Frances Carpenter |

| Жанр | Учебная литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Учебная литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781462902903 |

Every mishap in the household the children blamed on these tokgabis, poor wandering spirits who had never found their way up to heaven. A tear in a paper windowpane, a lid falling into a boiling pot, the evening rice burned—all these were surely the work of the tokgabis, the children thought.

"If you should ever meet a tokgabi," Halmoni told the children, "stand up so straight and proud that you look down upon him. Take out a bit of shining silver, a strip of red cloth, or a charm made from the wood of a lightning-struck tree. Then he will go away."

Along the ridges of the Kim roofs stood tiny clay figures of strange animals and ugly little men, put there to frighten the bad spirits away. A picture of the fat kitchen god was kept on the god shelf over the stove to prevent them from spoiling the family meals. Ok Cha and Yong Tu had learned always to step high over a threshold, lest they tread on the good guardian spirit of the house, who might be lying across it. They knew there were good spirits as well as bad. One could never be sure which were about. It was well to be careful.

As real to Halmoni and her grandchildren as their ancestors' spirits were all these unseen beings. When the old grandmother told of a man turned into an ox, of a cat whose fur dripped rice, or of a woodcutter who came upon the gods of the mountain playing at chess, they were sure such things could happen.

"I heard these tales from my own grandmother," Halmoni used to say. "How then can they not be true?"

"Always, Yong Tu, there have been poets and scholars in our family," said Halmoni. "They were true masters of wisdom who won high office at court."

LAND OF

MORNING

BRIGHTNESS

IN HALMONI'S ROOM, while the others talked in the light of the fish-oil lamps, Yong Tu sat apart at a little low table. The boy had opened one of the shining wood chests and had brought out his writing tools—his little inkstone, his ink paste, and his soft, fine, rabbit-hair brush. Squatting in his corner, he bent over a long strip of white paper, upon which he was making painstaking brush strokes. No one noticed what he was doing until he stood before his grandmother, paper in hand.

"Out on the hills today, Halmoni, I thought of this poem for the Honorable Ancestors. I have set it down to show you," the boy said somewhat shyly.

On all occasions the members of the Kim family, big and little, liked to make up poems and songs. Poems were like spring blossoms, they said; they always gave pleasure. Today Yong Tu's was the best among those of all the children. His poems were usually the ones to be hung on the walls of Halmoni's room.

"Like the phoenix among fowls,

Like the tiger among beasts,

You shine in the throngs

At the Heav'nly Emperor's feasts."

"Well done, my young paksa," Halmoni cried when the boy had read his little poem aloud for the family. "Your arrows hit the mark as neatly as those of Chu Mong, the Skillful Archer, whom men used to call 'Light of the East.'"

"Isn't it time for that story now, Halmoni?" Ok Cha begged, looking up into the kind twinkling eyes of her old grandmother. Often on days like this when the ancestors were especially honored, the old woman liked to tell of the beginnings of their land, and of the very first ancestors of the Korean people. Among them, she always said, were persons named Kim, for their family, as everyone knew, was one of the oldest and most honorable in all the land.

"Yé, the Master of' this House is departing. I will tell you the story. I shall speak first of Tan Kun, the Lord of the Sandalwood Tree. He came even earlier than did Chu Mong, the Skillful Archer. It was in the very beginning when our country first rose out of the sea. With its ten thousand mountain peaks on its back, our land mounted the waves like a great dragon.

"Marvels took place in those times, my children. Tan Kun was the son of a spirit from heaven and a beautiful bear-woman. His father, they say, was Han Woon, the very son of Hananim, the Lord of Heaven and Earth. When Han Woon came down to the earth, he brought with him thousands of his spirit friends. Among them were the Lord of Winds, the Ruler of Rain, and the Driver of Clouds. He set up his court under a great sandalwood tree. But all in it remained spirits. They did not take on human forms like those of the wild people who then roamed over the land.

"One day a she-bear and a tiger met on the side of the Ever-White Mountains, whose peaks hold back the clouds of the northern sky. As they talked, each beast declared that his greatest wish was to become a human being and walk upright on two legs. Suddenly a voice came out of the clouds, saying, 'You have only to eat twenty-one cloves of garlic, and hide yourselves away from the sun for three times seven days. Then you will have your wish.'

"The tiger and the she-bear ate the garlic and crept in out of the sunshine, far inside a dark cave. Now the tiger is a restless creature, my little ones, and the time seemed very long. At the end of eleven days he could stand the waiting no longer. He rushed out into the sunlight. Thus that tiger, still having the form of a beast, went off to his hunting again, on all four feet.

"The she-bear was more patient. She curled up and slept throughout the thrice-seven days. On the twenty-first morning, she came forth from the cave, walking upright on two legs, like you and me. Her hairy skin dropped away, and she became a beautiful woman.

"When the beautiful bear-woman sat down to rest under the sandalwood tree, Han Woon, the Spirit King, saw her. He blew his breath upon her, and in good time a baby boy was born to them. Years later, the wild tribes found this baby boy, grown into a handsome youth, sitting under that same tree. And they called him 'Tan Kun, Lord of the Sandalwood Tree.' They made him their king, and they listened well to his words.

"The Nine Tribes of those times were rough people, my children. In summer they lived under trees, like the spirits; in winter they took shelter in caves dug in the ground. They had not yet learned how to bind up their hair, to weave themselves clothing, nor to shut their wives away from the eyes of strange men. They knew nothing of growing good rice, nor of making savory kimchee. Their foods were the berries and nuts, the wild fruit and roots they found in the forests."

Halmoni paused a little to take a drink of the sweet honey water she liked so much. Then she continued her story.

"Tan Kun taught these wild people to cut down the trees and to open the earth to grow grain. He showed them how to cook their rice and how to heat their houses. Under his guidance they wove cloth out of grass fibers. They learned to comb their hair neatly, into braids for the boys and girls, into topknots for the married men, and into smooth coils for their wives.

"Good ways of living thus came to this Dragon-Backed Land. Tan Kun ruled it wisely for more than one thousand years, so my father told me. Our people had already begun to grow great when our second wise ruler came. This was the Emperor Ki Ja from across the Duck Green River, from China beyond the Ever-White Mountains."

"What became of Tan Kun, Halmoni?" Yong Tu asked.

"Tan Kun was no longer needed then, blessed boy," his grandmother replied. "He became a spirit again, and he flew back up to Heaven. But men say that an altar he built to honor his grandfather, Hananim, still stands on the faraway hills to the north."

Yong Tu knew all about Ki Ja, who is often called the "Father of Korea." It was written in the boy's own history book that, more than three thousand years ago, Ki Ja was an important official in China. He was unhappy under the wicked rule of the Chinese emperor who then sat on the Dragon Throne there. So he set forth to found a kingdom where people might live more safely and in peace.

"Five thousand good Chinese accompanied Ki Ja," Halmoni told her listeners. "Among them were doctors to heal the sick, and scholars to teach the ignorant people. There were mechanics and carpenters to show how cities could be built, and fortunetellers and magicians who knew how to keep away evil spirits.