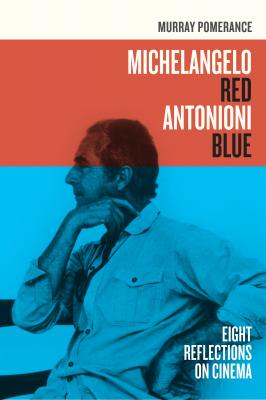

Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue. Murray Pomerance

Читать онлайн.| Название | Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Murray Pomerance |

| Жанр | Кинематограф, театр |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Кинематограф, театр |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780520948303 |

Change proceeds at such a pace that adults are disconnected from the sentiments of their own childhood. One is continually meeting people, continually thrust into the close proximity that makes possible readings of human intent and alignment. If the universe has not yet been evacuated of its aesthetic qualities—in Antonioni the universe is invariably such a place—the proximity invokes a kind of erotic studiousness, with the result that people are often, if swiftly, appraising one another and presenting themselves as possible partners in physical adventure. The contract, constraint, and discipline of marriage are a contradiction of the speeding allure of the world, and the characters we meet in this episode are all, to some degree or other—Carlo perhaps least, yet still appreciably—projected into the air that surrounds things, caught in transit as they move through the social space that supports their commitments and perceptions. The constant movement leaves emotion behind, replaces it with promise. Thus it is that we can be said to be marching ahead too quickly, to have left our souls behind, if our souls are our capacities for feeling and wonder. However, there is no practical way to stop and wait “until the souls catch up,” since territory itself has gained a new complexion as a space through which advancement can be achieved rather than a place of habitation. Locomotion has replaced habitation, anticipation has replaced experience.

When Patrizia moans “Ne me laisse pas!” she is surely already imagining a number of possible future considerations, that the American might disappear, as for three years now he has been threatening to; that she might be the one who does the leaving (as turns out to be the case). The “don’t leave me” is an utterance in regard to future possibility, not an outgrowth of present experience, a prayer not an observation, since at the moment he is comfortably wrapped in her arms and she in his. Even in warmth she can imagine the chill of motion. The chill of motion dominates her life. She and her husband are culturally, emotionally, and psychologically passengers, “human parcels who dispatched themselves to their destination” (Schivelbusch, Journey 38–39).

Everyone in this tale possesses or regards framed paintings or lithographs, and the artwork bespeaks the condition of those who exhibit it at the moment we see them. Perhaps the reflection is of a permanent or enduring condition. Carlo is perennially confronted with the back of a woman, a woman receding, a woman in departure, and this is why, although he is perturbed and angry, he is neither impossibly confused nor shocked. The young lover is perpetually in the presence of an inverted figure in agony or a watcher, perhaps always herself suspended in hunger or staring uncomprehendingly at the world. And Patrizia is to some degree always haunted by the specter of an artful, tasteful woman, a woman of style, who bends to take care of herself. Do the images predict the behavior that we see, or have the characters, living long with these images, learned to imitate them? Film, however, passes by and does not linger to haunt us as these framed pictures and forms do. We move through film much as these characters move through the city, through their time with one another. Time is “nothing but a disquiet of the soul” (Sebald, Emigrants 181).

Un Feu

It is not so much that feeling is impossible during the rush of modern experience, as that only feeling is possible, feeling but not the awareness of feeling, feeling but not the ability to speak of it. So, Carlo, Patrizia, her husband, and his lover make utterances that are notoriously practical—“I have come about renting the apartment”—or feverishly displaced—“For three years you have been bringing her smell here”—but in any event inarticulate about the true state of affairs overwhelming the inner world. Patrizia and her American husband straining to kiss through the plate glass partition of the shower stall, the partition that distends the lips and darkens the faces: what is this doomed project but an icon of the separation of men from their gods (who reside, of course, inside the creatures they serve)? Eager to negotiate and map territory, identity, position, possibility, miscalculation, the modern personality cannot connect with its own primitive hunger. The second glass partition in Carlo’s apartment: through it, a sighting takes place of moving personalities one and the other, a vacancy and an image where there might be a fire.

Let us imagine as we see them on both sides of this thick glass that Carlo and Patrizia will finally meet—meet, that is, after the few moments of preamble we have been entitled to see—and that they will remain in one another’s company, perhaps married, but certainly together in life, for a long time, a very long time by comparison with the abbreviated sentences which have filled the scenes so far, so that in the end, looking at the gross field of their lives and experiences, everything in this little filmed story will turn out to constitute only a caesura, a pause, a pit stop. Perez notes that L’eclisse begins at the end (367), so why might not this story, in an equally adumbrated fashion, present only the beginning, a beginning that is like an end? It becoming necessary for Carlo to explain to friends how he met Patrizia, he recounts this whole story, all of it given, no doubt, by her recountings to him of what she remembers—the twisting urgencies upon the bed, the smashed celadon, the repeated questions never answered—and her traumatic, exaggerated imaginations of the scenes she cannot possibly have witnessed. In the event, Carlo and Patrizia are a perfect couple, handsome, professional, businesslike, matter-of-fact, attuned to the moment, well-balanced (if precariously positioned), sane if not happy in their matching expensive suits—his the blue of midnight, hers the color of ice cream in the Tuileries—standing face to expressionless face, his darkness absorbing her brightness, his hopeless calm drinking in her sad frenzy. He speaks, this Carlo of the future, of what she recounted to him, but it is all a vision: the craven little mistress who dresses for seduction, invents