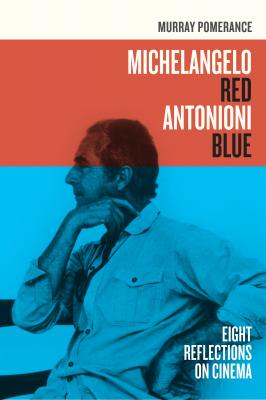

Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue. Murray Pomerance

Читать онлайн.| Название | Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Murray Pomerance |

| Жанр | Кинематограф, театр |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Кинематограф, театр |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780520948303 |

Once again they stroll along that portico beside their road, sunlight streaming through the archways. Their pace is casual but relentless, as though a riddle is to be worked out. He speaks of sunsets (in what one irked reviewer calls a “witheringly silly” line [Atkinson]). (Young people always want to have something to say.) They look up and see an icon of the Mother and Child appearing to bless them. Carmen talks about voices, suggesting that the voice is a creature, nervous, secretive. It’s strange, he muses, we always want to live in someone’s imagination; I like your eyes, completely empty of everything except sweetness. They kiss one another hungrily, and—oddly, because there is nothing of presence or intimacy that is not already given in the touch of these lips that have so artfully held back from intercourse with one another while still entreating and invoking so much with their hints of discourse—we approach, approach and judiciously examine, approach with hunger to see or know more. Then the scene fades, a conventional love story: that is, a story in which appetites are subject to etiquettes, in which conventions themselves are loved.

The Kiss

That we should approach, lean toward, that kiss! We have seen kisses onscreen before. For decades, they constituted the royal icons of cinema. Plainly enough, this one comes from passion, is erotic for both partners, surprises, and deeply pleasures. It escorts us to a new, or apparently new, depth. Yet, to learn this we need not dolly in. Does the camera movement perhaps provide explanation for—thus cover—our lingering interest in a sight that should normally seduce just a passing glance, for to let the shot run long with a steady camera might embarrassingly reflect a viewer’s attention back upon himself (even in the dark, where it cannot be optical relish for others, the rush of blood to the face is a palpable experience)? But the movement inward (or outward, away from ourselves, into ecstasy) produces in itself an interest and a payoff: not that something might be detected in the kiss with a closer view but as though the smooth gliding form of our fascination is a direct biophysical response to the kiss’s solicitation. We take leave of ourselves to kiss the subject matter of the film just as, smoothly and effortlessly, Silvano draws Carmen toward him in this kiss.

“HOTEL”

Dissolve. We discover our duo walking into the upstairs hallway of the hotel. She is leading him to her door. Centered in the frame is a pair of French doors giving out into the night, presumably over the forecourt, and through them we can see a bright turquoise neon sign, possibly “HOTEL”—it is visible only as a fragment—eerily agleam. (Only from inside, that is, do we see a sign that this is a hotel!) A shimmering reflection of this colored light is behind the boy’s back, around the doorframe of the room opposite Carmen’s. While she waits, he goes over to the French doors, opens them, steps out into the turquoise night, turning his face momentarily so that it is bathed in the rich undersea color. Then he steps back in, closes the doors behind him, says good night. Before going into her room, she follows him with her eyes, and we can see plainly enough that she is hungry for him. This is no dance of suspension and titillation for holding off the pleasure of a sexual encounter, for winding up the audience, but a careful and ritualized outplaying of fruitful ambiguity and doubt, the commonplace etiquette of modern life, when anticipations need not lead to resolution, when invitations need not lead to happiness.

In his pale green room, with its comforting vaguely Scandinavian lacquered wooden furniture and brown wooden doors, Silvano stands undecided. In her pale green room, Carmen slowly undresses after turning on her television. Having doffed his overcoat, Silvano mops his face with a towel, muses for a moment, quickly turns and opens his door to scan her territory—maybe she has left her door open a little, a hint. Nothing. He closes his door and turns off the light. Carmen is pulling on a prim pink nightgown, oblivious to some drawings made by her very young students taped to the wall behind her next to a small framed landscape and the television. She sits on her bed thinking (presumably of Silvano): “What is he doing? When will he come? What will he look like when we are warm together, when his neutral gray skins are slivered off?” She is certainly not thinking, “Curious, unappetizing man.” Antonioni’s skill is to give us what feels like certainty about the most intrinsic and private realities—what they are musing, each of them, alone—while also showing these realities to be unimportant, insubstantial. Silvano is sitting on his bed fully clothed while we hear a car pass by outside. He stretches out, pulls a blanket over himself, shows some anxiety as the scene slowly fades. In the morning, from above, we look down on him still asleep as cars pass one another on the busy road outside and someone sounds a horn. He rises in a trance but while tying his shoes seems suddenly to remember a girl … a girl who spoke of voices and kissed him. He moves out quickly to check for her. She has gone.

He asks the concierge to buy her some flowers. But it’s too late. Carmen and Silvano do not find one another again.

Two or three years go by.

In the modern world, which is the world in which yesterday has no hold upon tomorrow, the constant and enervating circulation that throws strangers against one another without introducing them produces a situation described by Georg Simmel, in which we experience a particular fear or perplexity that comes with seeing people we cannot hear (“Visual Interaction”). Carmen had told her knight earlier, “Voices never become part of you like other sounds.” She says you end up not hearing the sea, for instance, but “a voice you can’t help listening to.” Yet at the same time, these two say very little to one another, afford one another only briefly and superficially the opportunity to hear and know each other’s voice. They seem continually to pass like cars on a road, in a reflex that materially embodies our modern experience of social relationship: we see others without knowing them, relate to them only in a specific and particular way, applying ourselves to only a slice of their capacity and being. These two have no grounding beyond the hotel in which they spent the night, a dazed, neutral experience of the cars speeding by on the road outside, the soothing green walls that presumably relax and comfort them (as they do us) but that have been designed explicitly to soothe strangers who can be presumed to require soothing. No childhood memories in common, no labor, no plan for the future. Their lives are structured and scheduled according to different principles, on different tracks as it were, and once the night has passed there is little possibility—little reason—for them to connect again.

Two questions present themselves:

Why in the middle of the night does the boy not steal into the girl’s room? No one else is around to disturb them, she is directly across the hall, there is no reason to doubt that she has desire but in any event she would extend him every grace and gentility even if she refused. Is he afraid of sex? The nature of the kiss shows he is not. This question becomes increasingly perturbing when we note how slowly and self-pleasingly she slips off her underwear and her stockings, how she moves upon the bed in the silk nightgown, conscious of her body and its sensitivities, and when we reflect that as a schoolteacher devoted to her students (the drawings on the wall) she might not have many opportunities for meeting men, especially young and attractive men such as this one. As to him: without getting directions from her, he would never have found this hotel. Why does he hesitate? Could it be that he is thinking of making love to her, imagining the sensation of her body against his, wandering through the corners of a pleasure that has not yet been his, anticipating it with such concentration that the imagined pleasure, swollen, overwhelms him? Could the etiquette and shyness which is holding him back, coupled with the beauty of the anticipation, not produce a state of affairs in which, for him, the thought of romance is more pregnant than the act?

That is one. Another:

Why should Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo be invoked, as, surely, it is? Scottie Ferguson has followed the salesgirl Judy Barton to her home in the Empire Hotel on Sutter Street, a shabby environment with a turquoise neon sign outside the window. Having cajoled her into allowing him to dress and style her (so that through her he may invoke Madeleine Elster, his former object of fascination and obsession taken too early in death), Scottie is waiting in her hotel room for Judy to return from the hairdresser, and as he stands to look out her window he is bathed in the light of the turquoise sign. It is the same “hotel” light that bathes Silvano for a moment as, standing outside her room, he contemplates the possibility