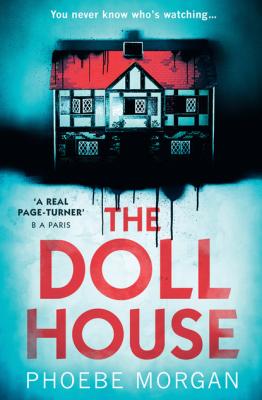

The Doll House. Phoebe Morgan

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Doll House |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Phoebe Morgan |

| Жанр | Контркультура |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Контркультура |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780008271695 |

I saw the fertility book in Waterstones the other day and found myself hovering, looking around to see if anyone was watching me research ways to have children the way other people look up hobbies. I picked the book up, started to carry it to the counter, but the woman in the queue looked at me sympathetically when she saw what I was holding. I left the shop in a hurry, cheeks flaming, unable to bear her pity, but that night I found myself on the computer with my purse open beside me, typing in my bank security details and our address.

I have forgotten that I am running a bath until I feel the ends of my dressing gown getting wet against my skin. The water has reached the rim of the tub and is threatening to overflow. Swearing, I reach for the tap and turn it off, plunging my hand down into the wet heat to release the plug. The book falls from my lap onto the floor, landing with a dull thud.

Once the bath water has resigned itself to an acceptable level, I undress, my dressing gown pooling on the floor. My stomach is flat, white. I imagine it stretched out in front of me, like Ashley’s was with Holly, and the hairs on my body stand up against the cold air, only relaxing as I slide into the hot water. I put my shoulders back against the enamel, feel the points of my shoulder blades flinch at the sensation. I lean down to pick up the book. I should be more open-minded. Perhaps it will work. After all, I am fast running out of options.

Around me, the water goes cold but I stay in the bath, letting my body relax. I used to have baths when I was a little girl, I’ve always preferred them to showers. Images of Carlington House keep surfacing in my mind; the way I screamed, the darkness of the windows. I need to get a grip. I’ve always been a bit like this. When I was a little girl, I was always thinking I saw faces, ghosts in the dark. There was never anyone there. Dad used to say I had an overactive imagination. ‘Seeing the spooks again, Corinne?’ He’d laugh, ruffle my hair. He thought it was funny, but actually it made me feel scared. Still. I’m an adult now, I ought to know better.

My mobile rings twice, a sharp trill followed by a thudding vibration that echoes through the silent flat, but I don’t want to get out of the water just yet. It’s probably my sister. As the sound of the phone begins again, I give up and sink my head under the water, enjoying the cold rush enveloping me, my hair floating up and around me like a dark halo.

The next thing I know, Dominic is shouting, his hands are underneath my armpits, slipping and sliding, and there is water splashing everywhere. The bath mat is bristly under my feet and the towel as he rubs it over me is rough. My teeth are chattering and my fingertips are prune-like. He has pulled the plug and the water is draining out, forming rivulets around the sides of the sodden paperback lying on the floor of the tub.

‘Jesus Christ, Corinne,’ Dominic says, and his voice is shaky.

I blink, focus on his hands as they wrap my dressing gown around me. I can’t quite work out why he’s so worked up. Did I close my eyes in the bath?

Dominic is still staring at me, shaking his head from side to side. There is a funny gasping sound that I realise is coming from me. I need to think of something to say.

‘Did you pick up the dinner?’

13 January 2017

London

Ashley

Ashley shifts her daughter from one hip to the other so that she can bend to pick up the mail on the doormat. Holly lets out a cry, a short, sharp sound followed by a wail that makes the muscles in Ashley’s shoulders clench. Every bone in her body is aching. Her hands clasp Holly’s warm body to her own; her daughter’s soft, downy hair brushes against her chest and she feels the familiar aching thud in her breasts. Please, not now.

She feels exhausted; even on days when she’s not at the café it’s as though she’s on a never-ending treadmill of nappies and tantrums, homework and school runs. It’s not as if James is around to help her; her husband has been staying at the office later and later, leaving early each morning before the children are even out of bed. He is pulling the sheets back usually around the time that Ashley is starting to drift off to sleep, having spent the night rocking Holly, trying to calm her red little body as she screams. She has never known anything like it; her third child is by far the most unsettled of the three. It has been nine months and still Holly refuses to sleep through the night; if anything she is getting worse. Ashley doesn’t think it’s normal. James stopped waking up at around the four-month mark, has been sleeping lately as though he is dead to the world. She doesn’t know how he manages it.

Ashley had woken yesterday to find his side of the bed empty and the sound of the tap running in their bathroom. She had put her hand to the space beside her, sat there mutely as her husband gave her a brief kiss on the cheek and headed out the door. As he had leaned close to her, Ashley had had to fight the urge to grip his shirt, force him to stay with her. She hadn’t, of course, she had let him go. Then she had been up, bringing Benji a glass of orange juice, placing Holly in her high chair, making coffee for her teenage daughter Lucy. On the treadmill for another day.

Working a few shifts a week at Colours café is her one respite, her only time when she is no longer a tired mother or a wife, she is simply a waitress. James had laughed at her when she decided to start working at the little café on Barnes Common, with the ice creams and the till and the tourists. He had been amazed when she insisted on continuing work a few months after having Holly, strapping her daughter carefully into the car and driving her across the common to their childminder.

‘You don’t need to now, honey,’ he used to say, before giving her little pep talks on the latest figures of eReader sales, on how well his company was doing. She knows they don’t need the money any more. But the waitressing isn’t for the money – most days she even forgets to pick up the little tip jar that sits at the edge of the counter, ignores the dirty metal coins inside as though they are nothing more than the empty pistachio shells that Lucy leaves in salty piles around the house. Ashley has always been happy to give up her publishing career for her children, but she craves this small contact with the outside world. The easy days at the café give her insights into other people’s lives, a chance to be in an adult environment. Just a few times a week, when she becomes someone else, someone simple, leaves her daughter in the capable hands of June at number 43 and walks back to her car alone, her arms deliciously light, weightless. It isn’t about the money.

June has been a godsend to Ashley in the last six months. A retired schoolteacher, she had been recommended to them a couple of months after Holly was born. Neither of them had been coping very well and the offer of a childminder seemed like a golden ticket, a chance opportunity that might never come again. Neither Benji nor Lucy had ever had a babysitter. Ashley had stayed at home all hours of the day and night, playing endless games of peek-a-boo and living her life on a vicious cycle of nappies and tears. Not that she’d minded at the time, not really, but now that she is older she finds her mind wandering, her energy limited. To be able to work in the café is bliss.

June is unwaveringly kind, and Ashley is overwhelmingly grateful to her for stepping in a few days a week. As far as she knows, the woman lives completely alone, has never had children of her own. Ashley can sense the sadness there, is happy to see the joy in June’s eyes when she drops off Holly. Yes, June really has been a blessing.

Ashley has thought about asking Corinne to mind Holly, but she has the gallery, and besides, Ashley doesn’t want it to upset her. Her sister’s emotions are so close to the surface at the moment, spending all day looking after someone else’s child rather than her own might have been too much.

It took Ashley seconds to make the decision last week. When Corinne had called with the doctor’s news Ashley had gone straight to her laptop and transferred her sister the money for her final round of IVF, thousands of pounds gone with a wiggle of the mouse. Still, it’s for the best. The money would only have been accumulating dust in their joint account. She hasn’t told James yet, has barely had the chance. She can hardly tell him at midnight, when she is half