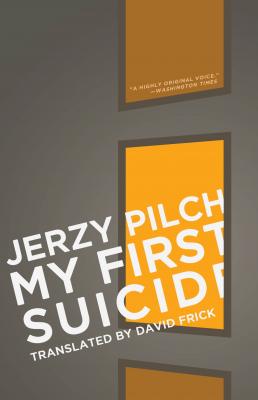

My First Suicide. Jerzy Pilch

Читать онлайн.| Название | My First Suicide |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Jerzy Pilch |

| Жанр | Современная зарубежная литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Современная зарубежная литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781934824672 |

Besides, Mr. Trąba began to answer, favorably inclined—in my opinion, excessively inclined. He began to answer eagerly, but chaotically, which was no wonder—the visible range of her solarium suntan shattered not only his concentration. Even Father Kalinowski had problems with the welcoming homily. At least he didn’t get tripped up on the Our Father.

The first hymn was sung, food served at the table, glasses filled. Eat and drink, and make merry, brothers and sisters! Quickly the company began to raise toasts based on cheerful biblical citations and deliver speeches composed on the model of sermons. I was delighted. I was delighted by the entire event. I was delighted by the speeches and the toasts. I was delighted by the fledgling singer in the lizard-green dress. I believed deeply that we would remain forever in my parts, and that in the evenings, in a house buried in snow, we would drink tea, watch films on HBO, etc. I was totally moved, and I was crazy about the absolute grandeur of the thing. When my turn came, or when I had the impression that my turn had come, I was close to tears from emotion. I tapped on my glass with the knife, I stood up, and I let ’er rip. It seemed to me that I was speaking incredibly fluently, that I was master of the form, and that I was faultlessly making my way to the conclusion, and I was simultaneously conscious that some force beyond my control was leading me astray, and that at any moment I would say something I shouldn’t, but which, at the prompting of the darknesses gathering in me, was becoming necessary.

At first, I told them some bullshit from my childhood. Then I began, with bootlicking servility, to assure everyone present that all my life I had emulated my folks, that I had striven to live as they do—according to God’s commandments. And even when it happened that I sinned, it was also—a paradox, but nonetheless—in emulation of them. And here I veered off into muddiness, or more precisely, I got carried away in absolute muddiness. I really must have heard Satan’s whisper, since I suddenly began to blather embarrassingly about how, after passing the matura, at the threshold of my university studies, I didn’t go to the dam in Porąbka, or to the camp in Auschwitz, or even to the Błędów Desert, but to my girlfriend at the time… to my girlfriend at the time… to my girlfriend at the time… I got flustered, since I sensed, after all, how terrible it was. I glanced in the direction of the fledgling singer, who was like a half-naked and emerald-winged angel among the Puritans enshrouded in their blacks; I glanced at her, and I didn’t want to say what I was just about to say; I didn’t want to say what I said, but my speech was now coming like a hemorrhage, as if I had been shot through the head. I didn’t go then to the dam in Porąbka, or to the camp in Auschwitz, or to the Błędów Desert, but to my girlfriend of the time, and my current wife. I added this unexpectedly, and I bowed in the direction of the fledgling singer, who sat quietly and didn’t even laugh; quite clearly she was thinking that it had to do with some Lutheran custom that was unknown to her—and my current wife, with whom I have been for nearly thirty years now, and with whom, I trust, I will live to see an anniversary like yours, dearest parents. Amen. God help me! God hear me! God forgive me!

I strove for grandeur, but I flew down into the depths of the abyss. I raised my glass, I turned toward the venerable celebrants, and, no amazement on my part, I saw a couple of elegantly dressed oldsters, frozen in horror (he in his best steel gray suit from the seventies, she in a fancy navy blue dress from the eighties), their heads hanging low, almost on the table cloth. Everyone, it goes without saying, grasped at once what a truly terrible gaffe I had committed, and no one—not even Father Kalinowski—hastened to smooth the situation over or to give me some sort of light-hearted support. I instantly understood what was going on. I returned to lucidity. I stood for another moment like the typical class dunce, who is still standing, although he ought to have taken his seat long ago. I stood for about another half a minute, and finally, in deathlike silence, I sat down on my chair. Copious sweat appeared on my forehead—I knew that I would have to suffer punishment.

The cooks brought in the second course, but the beef roulades and the veal cutlets were not salvation, they signified only a delay full of torment. Anyway, I didn’t have to wait long. My old man didn’t even try the second meat dish, he chewed a bit of the first (in other words, the roulade), stood up from the table, and went to change into his work clothes. A first, a second, a third slamming of doors reached us from the depths of the house, and after a moment the rhythmic pounding of a hammer resounded from the garage. The Lutherans, who were gathered around the table, relaxed a bit, began to glance at each other with recognition, and they smiled with pride: it is well known that when something bad happens, when the demons come, the best thing to do is to get to work. In spite of the horror of the situation, or perhaps on account of that horror, the question suddenly began to torment me: What sort of task had my old man set himself, and what was he so rabidly hammering?

Mother bustled over to the kitchen. I flew after her, I stood by the window, and I glanced at the snow-covered garden. “Mama,” I said quietly, “I’m sorry. I didn’t realize.” She turned toward me, a monstrous fury—all the more monstrous, because it was silent—contorted her face. She began to threaten me in silence, to make signs—toward the garage, in which my old man might die any moment from overwork; toward the dining room, in which the guests now sat, left to themselves—and she threatened me with all her might. For a good two, three minutes she didn’t say a thing; in the end, however, she couldn’t stand the pressure of the silence; she stood on tiptoe, and she hissed: “How could you lie! How could you lie about going on an excursion to the dam in Porąbka, to the camp in Auschwitz, or to the Błędów Desert, when you went who knows where!” “Mama,” I said with a trembling voice, “that was more than thirty years ago.” “And what if something had happened to anyone, how were we supposed to let you know? Where were we supposed to look for you. What if someone had died? What then? Everybody at home is certain that you are at the dam in Porąbka, in the camp in Auschwitz, or in the Błędów Desert, and you are who knows where! Alone to boot! And what if something had happened to you? Where did you go? To the mountains? By bus? But we had a car! Father would have driven you everywhere! I would have been glad to go myself! But you, you arrogant egotist, preferred to go alone! By bus! In the crush! Paying money for it! Instead of comfortably and for free! An entire life of worry!”

Mother covered her face with her hands and tried to summon up tears of despair—she wasn’t having much luck. The hubbub in the dining room was increasing. I didn’t have to be there to know that the fledgling singer in the lizard-green dress was beginning to figure out that something wasn’t right, that she was getting up from her place, that the remaining guests were interpreting this gesture as a demonstrative desire to leave the dinner, and they are attempting to stop her almost by force, that the amber suntan of my current love is turning pale as paper, and suddenly the terrified girl begins to assure them spasmodically that she doesn’t know what is going on here, and that she doesn’t know where she is at all; or what it is about; and she doesn’t have a clue where, and to whom, I travelled after my matura, because it certainly wasn’t to her! Perhaps I didn’t travel to the dam in Porąbka, to the camp in Auschwitz, or to the Błędów Desert, but it wasn’t to her either, because she wasn’t even born then! And she hasn’t been with me for thirty years, because she is only twenty-four years old, and why these absurd lies? Lutheran customs are one thing, but absurd lies are quite another matter!

Through four, five, and perhaps even six walls you could hear that the fledgling singer in the lizard-green dress was beginning to cry, that the Protestants surrounding her in ever tighter circles are first seized by agitation, but they immediately begin to calm down, and they attempt to calm her, too, and they defend me with all their might. They assure her emphatically that I hadn’t lied, and that I’m not lying, because Lutherans never lie, but that I speak the truth, and I pray for the truth, because what I had said was a prayer for truth, the prayer of a person who had strayed in a moment of weakness from the path of truth but prays for a return to that path, and my prayer was heard, and it became the truth. And through the walls I heard my current love’s scream,