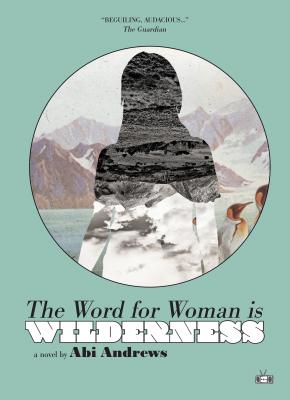

The Word for Woman Is Wilderness. Abi Andrews

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Word for Woman Is Wilderness |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Abi Andrews |

| Жанр | Исторические приключения |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Исторические приключения |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781937512804 |

Urla: Let me think, so, in nineteeeeeen seventy-five 90 percent of Icelandic women went on strike over equal pay and then they got equal pay. We elected the first female president in Europe in 1980. Finnbogadóttir. She was a divorced single mother like my mum and she was re-elected three times until she retired. And then our prime minister was the world’s first openly gay prime minister and she started out as an air hostess. The state church bishop is a woman. And we are the only country in the world to make strip clubs illegal for feminist reasons

— 4x4 magazine man makes a semi-discreet ‘humph’ sound — Urla turns to him pointedly — he looks down and flicks the pages of his magazine straight —

Erin: Do you think that has to do with nakedness being starker because in the cold climate you have to wear so many layers on a day-to-day basis? Kind of an anonymising of the human figure that might take away some issues of sexualising the body. Like in The Left Hand of Darkness, where cold and androgyny made a society with no misogyny and no war?

— 4x4 magazine man shakes his head disbelievingly — Urla does not notice — she looks down at her body in high-necked woollen jumper, thick grey joggers tucked into woollen socks —

Urla: I don’t know. Probably (PAUSE) what else. So women do not have to change their surname if they marry. And when a baby is born its parents get equal leave. BUT

— she raises her right index finger in a scholarly manner, holding the book to her chest with her other arm —

Urla: Even in the best place in the world in which to be a woman it is still better to be a man

— she looks at 4x4 mag man, who is leafing through his pages with a look of nonchalance —

Erin: Nowhere has completely got rid of gender inequality and the attitude of some people here now is like, Okay, we get it. You have everything you want now. You have it the best in the world so stop being so righteous. Other women don’t have it so great. You can give it a rest now. Although it’s totally cute when you get all angry

CUT

HOW TO BE A GROWN-UP IN A POST-FEMINIST SOCIETY

You are fourteen years old and you have just started your job as a waitress in a small restaurant owned by a family, each member of which fills a role in the kitchen and also deals drugs. Having never had a job you take everything here to be archetypical of the working world. You are not a feminist because feminists are lesbians and hate men and you don’t. You like boys more than girls, girls are lame and preoccupied and bitchy and you’d rather hang out with boys and skate and mess around. The only girls you do like want to be boys too.

Stuart is the father of the family and the manager of the restaurant. He is short, fat, bald, and has buggy eyes. When you are introduced from across the worktop he grabs your hand in his stubby, sweaty hands and kisses you up your arm with his fat wet lips. You squeak and recoil and the other girls laugh at you. When you are outside the kitchen one of the older girls tells you you get used to it.

You do get used to it and after a time you manage not to squirm when Stuart strokes your pubescent arse, which is taut in those tight-fitting Tammy Girl trousers he makes you wear because he likes it when you squirm. When he creeps up behind you when you’re standing behind the till counter on the restaurant floor and kisses you on the neck, making a squelchy sound, none of the customers ever say anything and some of them must catch him sometimes.

You watch a seventy-year-old man dine an escort while he strokes the downy hairs at the dip of your back and hips, while you tell yourself ‘the dip of my back and hips is merely the concave of a crescent in an assembly of matter which is a body in which I reside.’ When your mum asks how was work you say yeah, fine, because if you told her it’d be embarrassing. She’d call the police or something. None of the other girls have told anyone, the customers never say anything, so what makes you so special you call the police? It’s something you’re mature enough to ignore. It’s a part of being a woman. When Jodie the new girl starts you even get a bit annoyed when she keeps going on about how Stuart likes her because she’s prettier than you.

It’s an easy job and you don’t want to lose your job cuz then you won’t be able to go to the cinema or anything. If you quit you’d have to come up with a good reason for Mum and you can’t think of one. And you’re lucky to have this job because you’re really shit at it, they tell you that all the time. You do everything wrong and you’re really slow and clumsy and you never smile. And the other girls are always saying he’s good to us, he looks after us, he gives us free food and he’s like a dad really.

You let Stuart do it because it turns him on if you don’t. When you are in the cloakroom one time he calls your bluff and puts his fingers all the way down your underwear, which are the ones with ducks on them. You don’t tell the other girls because they’ll just think that you think that you’re something special. Nobody else is complaining, don’t be such a crybaby. When you close your eyes to sleep you can see clearly the spittle on his fat wet lips.

SYMBIOSIS OF ALGAE AND ANIMALS

Urla’s mother’s name is Thilda. Her house sits behind Reykjavík and from it you can look out over the backs of all the buildings looking out to the sea. It is spring and the trees and parks are very green and the water and sky very blue. The buildings get so close to the sea that in certain lights, when you can’t see the horizon and the harbours and the lakes are filled with sky, it can look as if the city is sitting on the edge of infinity. The sun sets but seems to sleep just out of sight, and I had to buy a sleep mask to convince my body it was night-time. Although it is getting warm for Iceland it is still cold, and whenever outside I wear my ski jacket.

Leaving Blárfoss had the potential to be emotional, but because for most of the others it was more of a suspension of the experience rather than an end — because most of the others would be repeating the journey again and again with slight variations in crew — it wasn’t. I will have to learn not to get emotionally attached to transitory places, seeing as a journey is entirely transition. Even Urla and Kristján treated their goodbye with admirable stoicism. She says that their relationship is Blárfoss, that they have agreed not to see each other outside of it before university finishes, and she does not think it can even exist independently of it. I think it is very sensible.

She seems to be able to look at their relationship with a manly and objective clarity that I admire. She seems totally indifferent to Kristján, in fact, spending most of her days on the boat with me, aside from joining him in their shared cabin at night. If they were together and I approached them, Kristján would make any excuse and leave, which became an ongoing joke to Urla; she would laugh and shout, ‘Bye, Kristján!’ after him. I got to feeling really bad about it and started to leave them be, but then Urla took to abandoning him for me.

She says as soon as university finishes she wants to do a trip like mine, that the trip is brave and important. She made me swell up, as if with her approval I become a little bit like her. She is sure of herself in a way that I envy, in the way that she talks and holds herself. You can tell she was one of the girls at school that everybody wanted to be friends with, or wanted to at least not to be not-friends with, to be in the focus of her dislike, which I imagine to be conducted with precision and ruthlessness.

At school I preferred to be on my own. I would ride my bike places on weekends, with my rucksack — an antidote to the typical feminine handbag — full of practical stuff that I would find use for even when it was tenuous, just for the sake of being able to cut everything neatly with my pocket knife even where I could use my teeth, nursing the smallest of wounds with my first aid kit, using my compass even when I knew the way just for the reassuring comfort I found in knowing exactly where north was, its orderliness and its simple truth, comfortable in apt autonomy like Thoreau.

There was one place in particular that I would cycle, an hour by