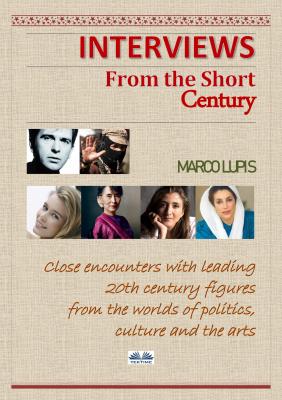

Interviews From The Short Century. Marco Lupis

Читать онлайн.| Название | Interviews From The Short Century |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Marco Lupis |

| Жанр | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9788873043607 |

Ten years off the grid is a long time. How do you pass the time up here in the mountains?

I read. I brought twelve books with me to the Jungle. One is Canto General by Pablo Neruda, another is Don Quixote .

What else?

Well, the days and years of our struggle go by. If you see the same poverty, the same injustice every single day... If you live here, your desire to fight and make a difference can only get stronger. Unless youâre a cynic or a bastard. And then there are the things that journalists donât usually ask me. Like, here in the Jungle, we sometimes have to eat rats and drink our comradesâ piss to ensure we don't die of thirst on a long journey...things like that.

What do you miss? What did you leave behind?

I miss sugar. And a dry pair of socks. Having wet feet day and night, in the freezing cold...I wouldn't wish that on anyone. As for sugar, it's just about the only thing the Jungle can't provide. We have to source it from miles away because we need it to keep our strength up. For those of us from the city, it can be torture. We keep saying: âDo you remember the ice creams from Coyoacán? And the tacos from Division del Norte ?â These are all just distant memories. Out here, if you catch a pheasant or some other animal, you have to wait three or four hours before it's ready to eat. And if the troops are so famished they eat it raw, itâs diarrhoea all round the next day. Life's different here; you see everything in a new light... Oh yes, you asked me what I left behind. A metro ticket, a mountain of books, a notebook filled with poems...and a few friends. Not many, just a few.

When will you unmask yourself?

I don't know. I believe that our balaclava is also a positive ideological symbol: this is our revolution...it's not about individuals, there's no leader. With these balaclavas, we're all Marcos.

The government would argue that youâre hiding your face because youâve got something to hide...

They don't get it. But itâs not even the government that is the real problem; it's more the reactionary forces in Chiapas, the local farmers and landowners with their private âwhite guardsâ. I don't think thereâs much difference between the racism of a white South African towards a black person and that of a Chiapaneco landowner towards a Mexican Indian. The life expectancy for Mexican Indians here is 50-60 for men and 45-50 for women.

What about children?

Infant mortality is through the roof. Let me tell you the story of Paticha. A while back, as we were moving from one part of the Jungle to another, we happened upon a small, very poor community where we were greeted by a Zapatista comrade who had a little girl aged about three or four. Her name was Patricia, but she pronounced it âPatichaâ. I asked her what she wanted to be when she grew up, and her answer was always the same: âa guerrillaâ. One night, we found her running a really high temperature â must have been at least forty â and we didn't have any antibiotics. We used some damp cloths to try and cool her down, but she was so hot they just kept drying out. She died in my arms. Patricia never had a birth certificate, and she didn't have a death certificate either. To Mexico, it was as if she never existed. Thatâs the reality facing Mexican Indians in Chiapas.

The Zapatista Movement may have plunged the entire Mexican political system into crisis, but you haven't won, have you?

Mexico needs democracy, but it also needs people who transcend party politics to protect it. If our struggle helps to achieve this goal, it won't have been in vain. But the Zapatista Army will never become a political party; it will just disappear. And when it does, it will be because Mexico has democracy.

And if that doesnât happen?

Weâre surrounded from a military perspective. The truth is that the government won't want to back down because Chiapas, and the Lacandon Jungle in particular, literally sits on a sea of oil. And itâs that Chiapaneco oil that Mexico has given as a guarantee for the billions of dollars it has been lent by the United States. They canât let the Americans think they're not in control of the situation.

What about you and your comrades?

Us? Weâve got nothing to lose. Ours is a fight for survival and a worthy peace.

Ours is a just fight.

2

Peter Gabriel

The eternal showman

Peter Gabriel, the legendary founder and lead vocalist of Genesis, doesn't do many gigs, but when he does, he offers proof that his appetite for musical, cultural and technological experimentation truly knows no bounds.

I met him for an exclusive interview at Sonoria, a three-day festival in Milan dedicated entirely to rock music. During a two-hour performance of outstanding music, Gabriel sang, danced and leapt about the stage, captivating the audience with a show that, as always, was much more than just a rock concert.

At the end of the show, he invited me to join him in his limousine. As we were driven to the airport, he talked to me about himself, his future plans, his commitment to working with Amnesty International to fight racism and social injustice, his passion for multimedia technology and the inside story behind Secret World Live , the album he was about to launch worldwide.

Do you think the end of apartheid in South Africa was a victory for rock music?

It was a victory for the South African people, but I do believe rock music played its part.

In what way?

I think that musicians did a lot to make people in Europe and America more aware of the problem. Take Biko , for example. I wrote that song to try and get politicians from as many countries as possible to continue their sanctions