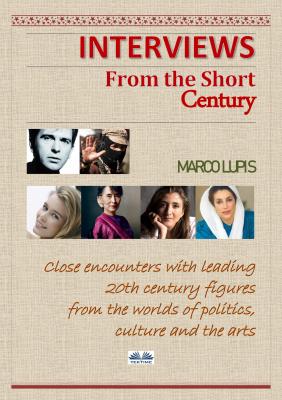

Interviews From The Short Century. Marco Lupis

Читать онлайн.| Название | Interviews From The Short Century |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Marco Lupis |

| Жанр | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9788873043607 |

1

Subcomandante Marcos

We shall overcome! (Eventually)

Hotel Flamboyant, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico. A message has been slipped under my door:

You must leave for The Jungle today.

Be at reception at 19:00.

Bring climbing boots, a blanket,

a rucksack and some tinned food.

I have just an hour and a half to get these few things together. Iâm headed for the heart of the Lacandon Jungle, which lies on the border of Mexico and Guatemala and is one of the least explored areas on Earth. In the present climate, no ordinary tour operator would be willing to take me there; the only man who can is Subcomandante Marcos, and the Lacandon Jungle is his last refuge.

*****

That meeting with Subcomandante Marcos on behalf of Corriere della Sera âs weekly magazine, Sette , remains to this day the proudest moment of my career. Even if I wasnât the first Italian journalist to interview him (I canât be certain that the likeable and ubiquitous Gianni Minà didnât get there first, if Iâm honest), it was definitely long before the fabled insurgent with his trademark black balaclava spent the next few years ferrying the worldâs media to and from his jungle hideaway, which he used as a kind of wartime press office.

It had been nearly two weeks since my plane from Mexico City had touched down at the small military airport in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the capital of the state of Chiapas, at the end of March. Aeroplanes bearing Mexican Army insignia were taxiing on the runway, and various military vehicles were parked menacingly all around. Chiapas was approximately a third of the size of Italy and home to over three million people, most of whom had Mexican Indian blood: some two hundred and fifty thousand were descended directly from the Maya.

I found myself in one of the poorest areas on Earth, where ninety per cent of the indigenous population had no access to drinking water and sixty-three per cent were illiterate.

It didnât take me long to work out the lie of the land: there were a few, very rich, white landowners and a whole load of peasant farmers who earned, on average, seven pesos (less than ten US dollars) a day.

These impoverished people had begun to hope of salvation on 1 January 1994. As Mexico entered into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the United States and Canada, a masked revolutionary was declaring war on his own country. On horseback and armed (albeit mostly with fake wooden guns), some two thousand men from the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) were occupying San Cristóbal de las Casas, the old capital of Chiapas. â Tierra y libertad! â [âLand and freedom!â] was their rallying cry.

We now know how that decisive first battle ended: the fifty thousand troops sent in with armoured cars to crush the revolt were victorious. But what about Marcos? What became of the man who had evoked memories of Emiliano Zapata, the legendary hero of the Mexican Revolution that began in 1910?

*****

Itâs seven oâclock at the reception of Hotel Flamboyant. Our contact, Antonio, arrives bang on time. He is a Mexican journalist who tells me he has been to the Lacandon Jungle not once, but dozens of times. Of course, the situation now is very different to how it was a year ago, when Marcos and his comrades enjoyed a relatively quiet existence in the village of Guadalupe Tepeyac, at the entrance to the jungle, equipped with phones, computers and the internet, ready to receive American television reporters. Life for the Mexican Indians has remained constant, but for Marcos and his fellow revolutionaries everything has changed: in the wake of the latest offensive by government troops, the leaders of the EZLN have been forced to hide in the mountains, where there are no phones, no electricity, no roadsâ¦nothing.

The colectivo (a strange cross between a taxi and a minibus) hurtles between a series of hairpin turns in the dark. The inside of the vehicle reeks of sweat and my clothes cling to my skin. It takes two hours to reach Ocosingo, a town on the edge of the Jungle. The streets are bustling and filled with the laughter of girls with long, dark hair and Mexican Indian features. There are soldiers everywhere. The rooms in the town's only hotel have no windows, only a grille in the door. It feels like being in prison. A news item crackles over the radio: âA man has revealed today that his son Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente, a thirty-eight-year-old university professor from Tampico, is Subcomandante Marcosâ.

A new guide joins us the next morning. His name is Porfirio and heâs also a Mexican Indian.

It takes us nearly seven dust- and pothole-filled hours in his jeep to reach Lacandón, a village where the dirt track ends and the jungle proper begins. Itâs not raining, but we're still knee-deep in mud. We sleep in some huts we encounter along our route, and it takes us two exhausting days of brisk walking through the inhospitable jungle before we finally arrive, completely stifled by the humidity, at Giardin. Itâs a village in the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve that is home to about two hundred people, all of whom are either women, children or old. The men have gone to war. We are made to feel welcome, but few people understand Spanish. Everybody here speaks the Mayan language Tzeltal. âWill we be meeting Marcos?â we ask. âMaybe,â Porfirio nods.

We are woken gently at three in the morning and told that we need to leave. Guided by the light of the stars rather than the moon, we walk for half an hour before we reach a hut. We can just about make out the presence of three men inside, but it's almost as dark as the balaclavas that hide their faces. In the identikit released by the Mexican government, Marcos was described as a professor with a degree in philosophy who wrote a thesis on Althusser and did a masterâs at Paris-Sorbonne University. A voice initially speaking French breaks the silence: âWeâve got twenty minutes. I prefer to speak Spanish if thatâs OK. Iâm Subcomandante Marcos. I'd advise you not to record our conversation, because if the recording should be intercepted it would be a problem for everybody, especially for you. We may officially be in the middle of a ceasefire, but theyâre using every trick in the book to try and track me down. You can ask me anything you like.â

Why do you call yourself âSubcomandanteâ?

Everyone says: âMarcos is the bossâ, but