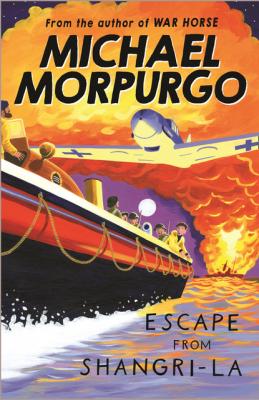

Escape from Shangri-La. Michael Morpurgo

Читать онлайн.| Название | Escape from Shangri-La |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Michael Morpurgo |

| Жанр | Учебная литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Учебная литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781780311579 |

He was right. He’d been right about everything. I felt a warm shiver creeping up the back of my neck. My grandmother had been called Cecilia, and I had been named after her, I’d always known that. There was a photograph of her on top of the piano in the sitting-room. She was young in the photograph, somehow too young for me to have ever thought of her as a grandmother.

I looked up into his face. The eyes were deep-set and gentle. They were blue. He had blue eyes. My father had blue eyes. I had blue eyes. That was the moment the last doubts vanished. This man had to be my father’s father, my grandfather.

For some time we just stood there and stared at him.

I squeezed my mother’s hand, urging her to do something, say something, anything. She looked down at me. I could see she was still unsure. But I knew he was not lying. I knew what lying was all about. I did it a lot. This man was not doing it. It takes a liar to know a liar.

‘You’d better come in,’ I said.

I broke free of my mother’s grasp, took my grandfather gently by the arm and led him into the warmth of the kitchen.

2 WATER MUSIC

‘I’M AFRAID I’VE GOT A VERY SWEET TOOTH,’ HE said, stirring five heaped teaspoons of sugar into his tea. We sat watching him as he sipped and slurped, both hands holding the mug. He was savouring it. In between sips he set about the plate of chocolate digestive biscuits, dunking every one till it was soggy all through, and devouring one after another with scarcely a pause for breath. He must have been really famished. His face was weathered brown and crinkled and craggy, like the bark of an old oak tree. I’d never seen a face like it. I couldn’t take my eyes off him.

I did all the talking. Someone had to. I can’t stand silences – they make me uncomfortable. He was obviously too intent on his tea and biscuits to say anything at all, and my mother just sat there staring across the kitchen table at him. How many times had she told me not to stare at people? And here she was gawping at him shamelessly. It was as if Quasimodo had dropped in for tea.

I had to think of something sensible to talk about, and I reasoned that he might want to know something about me, about his new-found granddaughter. After all, he had my whole life to catch up on. So I gave him a potted autobiography, heavily selective, just the bits I thought might be interesting: how we’d just moved here six months ago, where I went to school, who my worst enemies were. I told him in particular about Shirley Watson and Mandy Bethel, and about how they’d always baited me at school, because I was new perhaps, or maybe because I kept myself to myself and was never one of the girls. All the while he kept on chomping and slurping, but he was listening too. I could tell he was because he was smiling at all the right places. I’d told him just about everything I could think of, when I remembered my violin.

‘I’m Grade Five now. I started when I was three, didn’t I, Mum? Suzuki method. I do two lessons a week with Madame Poitou – she’s French and she’s a lot better than my old teacher. She says I’ve got a good ear, but I’m a bit lazy. I have to practise every day for forty minutes. Not much good at anything else, except swimming. Butterfly, I’m really good at butterfly. Oh, yes, and I like sailing too. Dad’s got a friend who works at the radio station with him, and he’s got a twenty-six footer called Seaventure. He keeps it down at the marina. We went all the way down the coast, didn’t we, Mum? Dartmouth or somewhere. Bit rough, but it was great.’

‘Nothing like it,’ he said, nodding away. ‘Nothing like the sea. “I must go down to the sea again, to the lonely sea and the sky . . .” you know that poem, do you? Not true, of course. You’re never lonely at sea. It’s people that make you feel lonely, don’t you think? You like poetry, do you? Always liked poems, I have. I’ve got dozens of them up here in my head.’

My mother spoke up suddenly: ‘How did you know where to find us? How did you know?’

‘It was luck, just luck. It wasn’t as if I was looking for him. It just happened. I was at home, a couple of weeks ago, and I had the radio on. Had it on for the weather, matter of fact. I always listen to the weather. I heard him, on that programme he does in the mornings. I didn’t recognise his voice of course, but there was something about how he said what he said that I had to listen to. And then I heard his name. “Arthur Stevens’ Morning Chat”, they called it. I’m not a fool. I knew well enough there was likely to be more than one Arthur Stevens in the world, I knew that. But I just had this feeling, like it was a meant-to-be thing. Do you understand what I’m saying? It was like we were supposed to meet up again after all this time.

‘So, the same afternoon it was, I went and had a look. I walked right in the front door of the radio station. And there he was, larger than life up on the wall, a huge great smiling poster of him. I took one look and, I’m telling you, I didn’t have to read the signature across the bottom. It was him. Same big ears, same cheeky smile, same little Arthur. Just fifty years older, that’s all. Couldn’t mistake him. And then, whilst I was standing there looking up at him, he comes right past me, close enough I could’ve reached out and touched him. And I wanted to, believe me I wanted to; but I couldn’t, I didn’t dare. Then he was gone out of the door and it was too late.’

He swept the biscuit crumbs up into a little pile with his finger, and went on. ‘Anyway, after that I came over all giddy in the head. I get that from time to time. I had to sit down to steady myself, and there was this young lady at the desk who helped me. She was nice too. She brought me a glass of water. I reckon she was a bit worried about me. After a bit, we got talking, her and me. I asked her about Arthur and she told me all about him – and about the two of you as well. She said how good he is to work with, how he cares about what he does. “Never stops,” she said. “Works himself to a frazzle.” She told me about all the shows he does, how they phone in with all their cares and woes, and how he talks to them and makes them feel better about themselves. “You should listen in some time,” she said. So I did. I’ve heard every one of his programmes ever since – never missed. Not once. Plays my kind of music too.’

He was looking at us hard. ‘I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking I’m maybe a bit crazed in the head, a bit barmy. Well, maybe I am at that. Maybe I shouldn’t have come at all. I’ve got no business being here, I suppose, not really, not after all these years.’ His eyes were welling with tears. ‘It was an agreement, a sort of understanding, between Arthur’s mother and me. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t blame her – I wasn’t much good to her, I know that now. One day she just said she’d had enough. She was leaving and she was taking young Arthur with her. She wanted a fresh start, she said. There was this other man – these things happen. Anyway it wasn’t nasty, nothing like that. It’d be best all round if I stayed out of it, she said, best for the boy. He’d soon get used to a new father. So I said I’d keep away, for the boy’s sake. And that’s what I’ve done. I kept my promise, and it wasn’t easy sometimes, I can tell you. A father always wants to know how his son’s grown up. So I never went looking; but when I heard his name on the radio, well, like I said, I thought it was a meant thing. And here I am. He sounded grand on the radio, just grand.’ He brushed away the tears with the back of his hand. He had massively broad hands, brown and engrained with dirt. ‘It took me two weeks thinking about it, and then a whole day standing out there in the rain before I could bring myself to knock on the door.’

He composed himself again before he went on. He was looking directly at my mother. ‘I haven’t come to bother you, nor him. I promise. I just wanted to see him, see you all, and then I’ll be on my way.’

My mother glanced up at the kitchen clock. ‘Well, I’m afraid he’s not going to be home for quite a while yet. Half an hour at least, maybe longer.’ Then, quite suddenly, she snapped into teacher mode again – positive, confident, organising. ‘All right,’