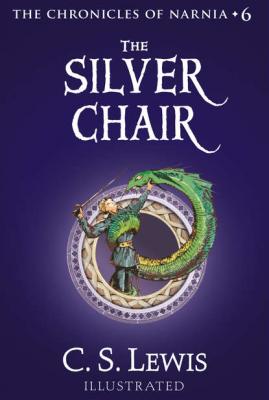

The Silver Chair. Клайв Стейплз Льюис

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Silver Chair |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Клайв Стейплз Льюис |

| Жанр | Детская проза |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Детская проза |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780007325092 |

Eustace gave a shudder. Everyone at Experiment House knew what it was like being “attended to” by Them.

Both children were quiet for a moment. The drops dripped off the laurel leaves.

“Why were you so different last term?” said Jill presently.

“A lot of queer things happened to me in the hols,” said Eustace mysteriously.

“What sort of things?” asked Jill.

Eustace didn’t say anything for quite a long time. Then he said: “Look here, Pole, you and I hate this place about as much as anybody can hate anything, don’t we?”

“I know I do,” said Jill.

“Then I really think I can trust you.”

“Dam’ good of you,” said Jill.

“Yes, but this is a really terrific secret. Pole, I say, are you good at believing things? I mean things that everyone here would laugh at?”

“I’ve never had the chance,” said Jill, “but I think I would be.”

“Could you believe me if I said I’d been right out of the world – outside this world – last hols?”

“I wouldn’t know what you meant.”

“Well, don’t let’s bother about worlds, then. Supposing I told you I’d been in a place where animals can talk and where there are – er – enchantments and dragons – and – well, all the sorts of things you have in fairy tales.” Scrubb felt terribly awkward as he said this and got red in the face.

“How did you get there?” said Jill. She also felt curiously shy.

“The only way you can – by Magic,” said Eustace almost in a whisper. “I was with two cousins of mine. We were just – whisked away. They’d been there before.”

Now that they were talking in whispers Jill somehow felt it easier to believe. Then suddenly a horrible suspicion came over her and she said (so fiercely that for the moment she looked like a tigress):

“If I find you’ve been pulling my leg I’ll never speak to you again; never, never, never.”

“I’m not,” said Eustace. “I swear I’m not. I swear by – by everything.”

(When I was at school one would have said, “I swear by the Bible.” But Bibles were not encouraged at Experiment House.)

“All right,” said Jill, “I’ll believe you.”

“And tell nobody?”

“What do you take me for?”

They were very excited as they said this. But when they had said it and Jill looked round and saw the dull autumn sky and heard the drip off the leaves and thought of all the hopelessness of Experiment House (it was a thirteen-week term and there were still eleven weeks to come) she said:

“But after all, what’s the good? We’re not there: we’re here. And we jolly well can’t get there. Or can we?”

“That’s what I’ve been wondering,” said Eustace. “When we came back from That Place, Someone said that the two Pevensie kids (that’s my two cousins) could never go there again. It was their third time, you see. I suppose they’ve had their share. But he never said I couldn’t. Surely he would have said so, unless he meant that I was to get back? And I can’t help wondering, can we – could we—?”

“Do you mean, do something to make it happen?” Eustace nodded.

“You mean we might draw a circle on the ground – and write things in queer letters in it – and stand inside it – and recite charms and spells?”

“Well,” said Eustace after he had thought hard for a bit. “I believe that was the sort of thing I was thinking of, though I never did it. But now that it comes to the point, I’ve an idea that all those circles and things are rather rot. I don’t think he’d like them. It would look as if we thought we could make him do things. But really, we can only ask him.”

“Who is this person you keep on talking about?”

“They call him Aslan in That Place,” said Eustace.

“What a curious name!”

“Not half so curious as himself,” said Eustace solemnly. “But let’s get on. It can’t do any harm, just asking. Let’s stand side by side, like this. And we’ll hold out our arms in front of us with the palms down: like they did in Ramandu’s Island—”

“Whose island?”

“I’ll tell you about that another time. And he might like us to face the east. Let’s see, where is the east?”

“I don’t know,” said Jill.

“It’s an extraordinary thing about girls that they never know the points of the compass,” said Eustace.

“You don’t know either,” said Jill indignantly.

“Yes I do, if only you didn’t keep on interrupting. I’ve got it now. That’s the east, facing up into the laurels. Now, will you say the words after me?”

“What words?” asked Jill.

“The words I’m going to say, of course,” answered Eustace. “Now—”

And he began, “Aslan, Aslan, Aslan!”

“Aslan, Aslan, Aslan,” repeated Jill.

“Please let us two go into—”

At that moment a voice from the other side of the gym was heard shouting out, “Pole? Yes, I know where she is. She’s blubbing behind the gym. Shall I fetch her out?”

Jill and Eustace gave one glance at each other, dived under the laurels, and began scrambling up the steep, earthy slope of the shrubbery at a speed which did them great credit. (Owing to the curious methods of teaching at Experiment House, one did not learn much French or Maths or Latin or things of that sort; but one did learn a lot about getting away quickly and quietly when They were looking for one.)

After about a minute’s scramble they stopped to listen, and knew by the noises they heard that they were being followed.

“If only the door was open again!” said Scrubb as they went on, and Jill nodded. For at the top of the shrubbery was a high stone wall and in that wall a door by which you could get out on to open moor. This door was nearly always locked. But there had been times when people had found it open; or perhaps there had been only one time. But you may imagine how the memory of even one time kept people hoping, and trying the door; for if it should happen to be unlocked it would be a splendid way of getting outside the school grounds without being seen.

Jill and Eustace, now both very hot and very grubby from going along bent almost double under the laurels, panted up to the wall. And there was the door, shut as usual.

“It’s sure to be no good,” said Eustace with his hand on the handle; and then, “O-o-oh, by Gum!!” For the handle turned and the door opened.

A moment before, both of them had meant to get through that doorway in double quick time, if by any chance the door was not locked. But when the door actually opened, they both stood stock still. For what they saw was quite different from what they had expected.

They had expected to see the grey, heathery slope of the moor going up and up to join the dull autumn sky. Instead, a blaze of sunshine met them. It poured through the doorway as the light of a June day pours