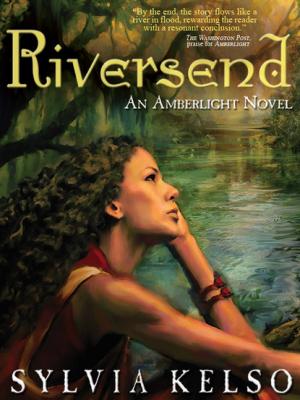

Riversend: An Amberlight Novel. Sylvia Kelso

Читать онлайн.| Название | Riversend: An Amberlight Novel |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Sylvia Kelso |

| Жанр | Историческая фантастика |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Историческая фантастика |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781479423200 |

She has never, I did not say, operated on any other terms.

“And that we—let her make the choice?”

What would be different?

“And,” he swallowed, “that we don’t—compete?”

There I finally woke to sense.

“We can agree whatever we like. The question is, what does she think?”

He clapped his hand back over his face. I caught at it in alarm, and he lowered it, with another long, shaken breath.

“I keep forgetting. I keep fouling it up.” He looked up at me with eyes where rage and jealousy were weirdly entangled with guilt. “And I used to think you were a—a—”

“Clothes-horse?” Whatever was in my smile, he winced. “That you’re outland doesn’t make you a fool.”

He started to speak. Stopped. Then he shook his head.

“And the code you talk . . . I’ll try to remember that as well.”

Then he thrust out the good hand and looked me straight in the eye.

“We let her make the rules, then. We try—I’ll try—not to fight over her. Not to—lose my head again. Not to,” a wry, bitter smile, “put it off on you.”

What use to recall the Tower, where he would have learnt to manage all this, or to let it out mannerly, from birth? I took his hand. When he let go, I decided he was chastened enough for the risk. I picked up the shirt for the third time and enquired, “And now, would you consider getting dressed?”

Mother be blessed, he laughed.

* * *

Wits, then, despite being outlander. Sharp enough to learn, perhaps. Certainly to encourage me in idiocy. So at the first hold-up that day, when half a bridge-span’s edge caved in under Zariah’s bullock-cart, and he scampered down to embroil himself in the uproar, I dared to touch his arm.

“What the—!” He had spun so fast I jumped back myself. “Oh . . . Gods, be careful doing that!”

It takes no troublecrew to know a killer’s reflex. But he was past that already. “What is it—uh—”

A fresh cascade of diggers and riggers poured round us, halfway down the flattening track past the bridge bastion. Good solid Iskan stone, with dry grass, and shadow, at its foot.

Following me into that, wary, almost suspicious, he repeated, “What is it—ah—Sarth?”

Another giant step. One, pest on him, I could only match.

“Uh—Alkhes. May I suggest something?”

The eyes focused. The eyebrows flicked. A gesture down into the creek, where they were wading about, disputing and quarrelling, around the debris. “About that?”

“Um. Yes.”

He waited. He was going to listen. More than you can say for Zuri’s lot, whose best response is a courteous pat on the rump.

“Just let them get on with it. It may take time, but it’s what they need.”

The eyes sharpened. “Need?”

I was far outside decorum. Far beyond my place, to explain women to an outside man. “Ask Tellurith. I have to get back—”

“Wait just one moment!” He actually caught my sleeve. The eyes skewered me. “Need what?”

“Ask her. I can’t explain it. It’s not my place—”

“What do they need?”

“It’s not my business, Alkhes!”

“All right, I’m sorry.” He came the step back with me. I have never seen the general, or the outlander, or the Mother-forsaken, terrifying wits of him, so clear. “I’ll ask Tellurith. I’ll think about it. They need their way. And,” the eyes sharpened, “it isn’t mine.”

He came with me up the bank, back to Charras’ bullocks, which I was trying to help drive that day. He held cups when I heaved the water-jar down for her three children; boiled water, to keep them from disease as well as the creek. He listened as we talked. Settled beside me, quiet, and willing, attentive as any novice, and terrifying as a leashed tiger-cub, in the shade where we decided to wait.

He would have been an ornament to a Tower after all. He does not learn by questions. He listens, and looks.

And thinks.

* * *

The Diaspora. Week 2.

Tellurith’s Diary

“Tel, what is it that you—your folk—need to do, that I can’t help?”

He had waited for that precious after-dinner lull, with last reports made, trouble sorted, Iatha and even Hanni gone; the space before baths and men’s time, the time I have kept for myself. He sat on his heels, a slight, lithe shadow in the ember-glow; the falling wing of hair crossed his eyes with paler night. I slid a hand through it, living silk under my fingers, while I thought.

“Why do you ask?”

Darkness folded. A frown.

“When the bridge collapsed today. He . . .” An almost audible gulp. “ . . . Sarth—said I should stay out of it. That they ‘needed’ it.”

I did not exclaim, Sarth? Probably I will never know what happened this morning. But a truce was miracle enough.

“Alkhes . . . Caissyl.” Incongruous to love-name this one Sweetness, yes. Unwise to say, You’ve been talking. I’m so glad.

“You’re a soldier. A general. You’ve probably forgotten more about marches—and road-making—than we’ll ever know.” He did not trouble to nod. “You think I ought to use that; and I would. Except . . . do you remember the soap?”

The black brows came together. A moment’s pause. And then a softly indrawn breath.

“If a general wants to spoil the water, he can. No question. But you thought—remembered—considered—everyone else.”

Never, yet, have his wits failed me. Never, yet, have they failed to exceed my aim. But when I nodded, I felt the renewed frown.

“So what’s wrong with considering—trying to help?”

“Two things. First . . .” I held out a hand. He eeled closer, into my arm.

“First. You still try to help like a general. You want to—go in from the top. Give orders, arrange, direct things. Do it as clean and fast as anyone can.”

The hurt was clear as a cry. He had been so sure he was doing better, paying attention, thinking of other people. I gave his shoulder a little shake.

“The second thing . . . I’ve pulled them out of the City. Out of places, and crafts, and ranks that were settled, fixed, longer than their lives. And I’ve pulled down the towers. They have to fit the men in now, some way—altogether new. And the men have to fit. Do you know what Sarth’s gone through, just learning to swing a mallet? Have you seen his hands? And do you notice the way the women still have trouble hearing him? When he does have something to say?”

His head was bent, his eyes on the fire. After a moment he said very quietly, “Damn, how much more have I missed?”

“I doubt you could have helped that. Even with Zuri’s crew. Not yet. But . . .”

He turned to me this time. Swinging on his heels to put the good hand, light, if without its usual feather deftness, to the haft of my plait. But he did not urge, Go on.

“And there are all the—people who—died.”

Craft-heads, Navy captains,