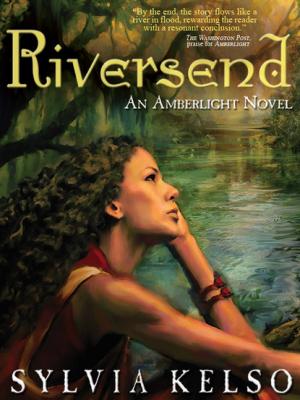

Riversend: An Amberlight Novel. Sylvia Kelso

Читать онлайн.| Название | Riversend: An Amberlight Novel |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Sylvia Kelso |

| Жанр | Историческая фантастика |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Историческая фантастика |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781479423200 |

“You want the craziest things.” He was trying, like a man trying to walk with a broken leg, to smile. “And I can’t imagine how to—but I’ll try.”

“Oh, Sarth.” What sweet thankfulness, to come into his arms as Alkhes had into mine, to rest in safety, however briefly, my head on his chest.

“Oh, Tellurith.” He smoothed my hair. “And now; what is it you want me to do?”

“I just thought—it was just an idea—”

“Just thought what?”

“We had this problem—”

“What problem?”

“I, ah— Tell me, can you shave someone else?”

“Naturally, we all learnt.” The hidden smile was dying. Too much like recall to that frivolous, pointless life. Then his voice changed. “You don’t mean—”

“Sarth, he’s broken an arm and three ribs and he’s been riding after us four days— Somebody has to do it! And I don’t know how and outlanders are funny about depending on women at the best of times, and I thought—I thought—it would be a start . . .”

His muscles jerked and I nearly cringed. I had feared Sarth in malice. I had never felt him approach rage.

“Forget it, it was stupid, I’ll think of something else . . .”

“No.” The anger checked. Then he sighed and let me release myself. “I’ll do it. You have enough to think about.”

I kissed him. He held me gently, but close. When I stood back this time, the bystanders read it as conclusion, and moved in from all directions. I did not see him walk away.

* * *

The Diaspora. Week 1.

Journal kept by Sarth

He was so blasted small. I stamped into that tent ready to bite him in half and spit out the bits, and he was huddled up on the floor against a saddlebag. Like a twelve-year-old bridegroom, just brought into the Tower. So blasted small . . . .

He must have been half asleep. He felt me come in, jumped up, hit his arm—or the ribs—and doubled up. I grabbed him, down on my knees, before I thought. I’ve seen so many children come into the Tower. Little. Uprooted. Afraid.

“Steady,” I think I said. “It’s all right.”

We were staring, a foot apart. He has these enormous eyes. Far too big for a grown man. Black as pitch. A whole night sky, in one human face.

He knew me, without a doubt. He tried to straighten—or stand up, outland soldiers have pride but absolutely no wits. “Whoa,” I said. I had been prodding draught-bullocks all day. “I’ve seen Tellurith.”

The last time we met he had seemed twice my size. An avenger, a demon with a dagger who filled Tellurith’s rooms to the roof. And he threw me out. It should have been pleasant, to know we had exchanged boots.

I felt the bones in his shoulder move. Below its padding the faded roan infantry tunic bulked awry; the bandage round his ribs. His fingers clamped the bad arm’s wrist.

“What did she say . . . to you?”

The ribs had pinched his breath. It came out ragged. Masking the intonation. Telling me more about damage, and exhaustion, and being here alone, an exile, than Tellurith had explained.

I could have retorted, I imagine you know, or even, Don’t you know? I could have said, Another of Tellurith’s crazy ideas. She wants to marry us both. Or, She expects me to open gates with you. Somehow. But the first two were war-signals, and the next friends’ talk. And the last was franker than I could manage. Then.

We were still staring, all but nose to nose. The eyes had got bigger. Or the face had shrunk, under the beard-shadow, the bruise. A scrap of a man, hurt, tired, hunted into a corner. Cold. Afraid.

I had moved before I knew it, too. As if he were just another new, unkempt boy. I pushed the hair out of his eyes and drew my palm on down the black bristle on his jaw.

“She asked,” I said, “if someone could help you shave.”

He froze solid. I should think his very heart stopped. And in that moment, I understood.

Just as he took a great breath, and clutched his ribs and got out through it, “ . . . never know—how m-much . . .”

The ribs pinched him on the stammer, that came from his chattering teeth. The sense was clear as a flag. Relief; apology; thankfulness; gratitude, decently controlled.

I found the cameleer’s jacket they had given him, and put it round his shoulders. Outside it was quite dark, and the sound of Shia’s pots said supper was close. “It’s warmer out there,” I said, “though you may not believe it. And I could do with supper first.”

We did not wait for Tellurith. He was past keeping a House-head’s schedule, whose one certainty is Late. Azo, of all people, dour scar-cheeked troublecrew, cut up what meat Shia missed, so he fed himself. My own razor was in the camp gear. Imported ivory handle, chased Dhasdein steel. Shia let me thieve hot water. We went back inside, for the steadier light, he splashed water and worked up a lather one-handed. I took the razor, and gathered myself up.

And he shut his eyes and lifted his face like a child ready to be washed. Offering me, offering the razor, his unprotected throat.

* * *

Tellurith was back before we finished. A shadow against the coals, head tilted from the papers in her lap. Bronze-crinkle Craft plait, every hair etched by firelight, the high cheekbones and arrogant jaw. Features I can shape from memory, in the dark, in my sleep. Like the question, the anxiety, the dawning, vindicated, once more successful gleam in those narrow chestnut eyes.

“There you are.” Scrambling up to meet us, a hand on my chest, on his intact arm. A smile for me. For him a scrutiny, then a butterfly, multiply significant touch on the cheek.

And then to me, “Do you want the last hot water, before we turn down?”

Old House usage. Dim the qherrique, that was both light and heat, for the night. Not so subtle reminder that they had bathed, as I had not. Horrifying signal that she was going to throw us all in bed together. Right now.

I think I managed not to gulp. Hot water? I wanted a full, hour-long bath. I wanted skin softener and hair wash and perfume, a manicure, my eye make-up, a face-veil and jewelry, sheets on my bed. Not to wash and shave by guess behind a wagon in the cold and dark, then fall into dirty blankets with my hair still stinking of sweat. And not, Mother save us, with another man!

One is grateful, at times, for the discipline of the Tower. I was thankful, at least, that she waited for me by the coals rather than give him first possession of the tent. Even if she waited in his arms.

The tent was a Verrain subaltern’s, built for one man and his servant, and that only while he dressed. It was actually an honor that Tellurith had one, technically, to herself. Otherwise we would have bedded down in the big infantry shelter. Figure such antics under the eyes of Shia and Azo and Hanni and her husband, and the Mother knows who else.

The Tower taught me, long ago, the dance of entry and apportion in shared territory, but it is always so delicate. This one was damnably delicate. And I was so tired. So tired I sat down like a peasant on a pack-bag and left arrangements to Tellurith.

So it was my own fault we wound up with a blanket on the ground canvas under us, and two beneath the Dhasdein officer’s cloak atop. And Tellurith nearest the door—“in case there’s trouble in the night”—and me against the wind-side wall. And the third between us: on his side to protect his broken ribs, and his bad arm, if you please, pillowed on my chest. “Because you’re the right size, Sarth. And you don’t thrash about.”

It is true,