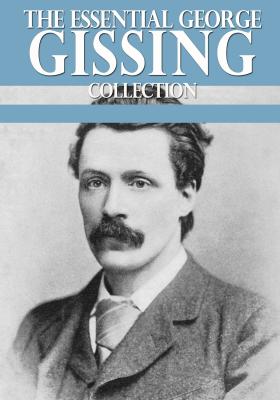

The Essential George Gissing Collection. George Gissing

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Essential George Gissing Collection |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | George Gissing |

| Жанр | Контркультура |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Контркультура |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781456613723 |

"A deplorable state of things!" exclaimed Irene, laughing.

"Yes--or no. Who knows? Such people ought to die young. But I don't say that it is invariably the case. To be capable of loving, and at the same time to have other faculties, and the will to use them--ah! There's your complete human being."

"I think----" Irene began, and stopped, her voice failing.

"You think, _belle Irene_?"

"Oh, I was going to say that all this seems to me sensible and right. It doesn't disturb me."

"Why should it?"

"I think I will tell you, Helen, that my motive in marrying is the same as yours was."

"I surmised it."

"But, you know, there the similarity will end. It is quite certain"--she laughed--"that I shall have no six-months' vacations. At present, I don't think I shall desire them."

"No. To speak frankly, I auger well of your marriage."

These words affected Irene with a sense of relief. She had imagined that Mrs. Borisoff thought otherwise. A bright smile sunned her countenance; Helen, observing it, smiled too, but more thoughtfully.

"You must bring your husband to see me in Paris some time next year. By the bye, you don't think he will disapprove of me?"

"Do you imagine Mr. Jacks----"

"What were you going to say?"

Irene had stopped as if for want of the right word She was reflecting.

"It never struck me," she said, "that he would wish to regulate my choice of friends. Yet I suppose it would be within his right?"

"Conventionally speaking, undoubtedly."

"Don't think I am in uncertainty about this particular instance," said Irene. "No, he has already told me that he liked you. But of the general question, I had never thought."

"My dear, who does, or can, think before marriage of all that it involves? After all, the pleasures of life consist so largely in the unexpected."

Irene paced a few yards in silence, and when she spoke again it was of quite another subject.

Whether this sojourn with her experienced and philosophical friend made her better able to face the meeting with Arnold Jacks was not quite certain. At moments she fancied so; she saw her position as wholly reasonable, void of anxiety; she was about to marry the man she liked and respected--safest of all forms of marriage. But there came troublesome moods of misgiving. It did not flatter her self-esteem to think of herself as excluded from the number of those who are capable of love; even in Helen Borisoff's view, the elect, the fortunate. Of love, she had thought more in this last week or two than in all her years gone by. Assuredly, she knew it not, this glory of the poets. Yet she could inspire it in others; at all events, in one, whose rhythmic utterance of the passion ever and again came back to her mind.

A temptation had assailed her (but she resisted it) to repeat those verses of Piers Otway to her friend. And in thinking of them, she half reproached herself for the total silence she had preserved towards their author. Perhaps he was uncertain whether the verses had ever reached her. It seemed unkind. There would have been no harm in letting him know that she had read the lines, and--as poetry--liked them.

Was her temper prosaic? It would at any time have surprised her to be told so. Owing to her father's influence, she had given much time to scientific studies, but she knew herself by no means defective in appreciation of art and literature. By whatever accident, the friends of her earlier years had been notable rather for good sense and good feeling than for aesthetic fervour; the one exception, her cousin Olga, had rather turned her from thoughts about the beautiful, for Olga seemed emotional in excess, and was not without taint of affectation. In Helen Borisoff she knew for the first time a woman who cared supremely for music, poetry, pictures, and who combined with this a vigorous practical intelligence. Helen could burn with enthusiasm, yet never exposed herself to suspicion of weak-mindedness. Posturing was her scorn, but no one spoke more ardently of the things she admired. Her acquaintance with recent literature was wider than that of anyone Irene had known; she talked of it in the most interesting way, giving her friend new lights, inspiring her with a new energy of thought. And Irene was sorry to go away. She vaguely felt that this companionship was of moment in the history of her mind; she wished for a larger opportunity of benefiting by it.

Dr. Derwent and his son were now at Cromer; there Irene was to join them; and thither, presently, would come Arnold Jacks.

On the day of her departure there arose a storm of wind and rain, which grew more violent as she approached the Norfolk coast; and nothing could have pleased her better. Her troubled mood harmonised with the darkened, roaring sea; moreover, this atmospheric disturbance made something to talk about on arriving. She suffered no embarrassment at the meeting with her father and Eustace, who of course awaited her at the station. To their eyes, Irene was in excellent spirits, though rather wearied after the tiresome journey. She said very little about her stay in Hampshire.

The last person in the world with whom Irene would have chosen to converse about her approaching marriage was her excellent brother Eustace; but the young man was not content with offering his good wishes; to her surprise, he took the opportunity of their being alone together on the beach, to speak with most unwonted warmth about Arnold Jacks.

"I really was glad when I heard of it! To tell you the truth, I had hoped for it. If there is a man living whom I respect, it is Arnold. There's no end to his good qualities. A downright good and sensible fellow!"

"Of course I'm very glad you think so, Eustace," replied his sister, stooping to pick up a shell.

"Indeed I do. I've often thought that one's sister's choice in marriage must be a very anxious thing; it would have worried me awfully if I had felt any doubts about the man."

Irene was inclined to laugh.

"It's very good of you." she said.

"But I mean it. Girls haven't quite a fair chance, you know. They can't see much of men."

"If it comes to that," said Irene merrily, "men seem to me in much the same position."

"Oh, it's so different. Girls--women--are good. There's nothing unpleasant to be known about them."

"Upon my word, Eustace! _On n'est pas plus galant_! But I really feel it my duty to warn you against that amiable optimism. If you were so kind as to be uneasy on my account, I shall be still more so on yours. Your position, my dear boy, is a little perilous."

Eustace laughed, not without some amiable confusion. To give himself a countenance, he smote at pebbles with the head of his walking-stick.

"Oh, I shan't marry for ages!"

"That shows rather more prudence than faith in your doctrine."

"Never mind. Our subject is Arnold Jacks. He's a splendid fellow. The best and most sensible fellow I know."

It was not the eulogy most agreeable to Irene in her present state of mind. She hastened to dismiss the topic, but thought with no little surprise and amusement of Eustace's self-revelation. Brothers and sisters seldom know each other; and these two, by virtue of widely differing characteristics, were scarce more than mutually well-disposed strangers.

Less emphatic in commendation,