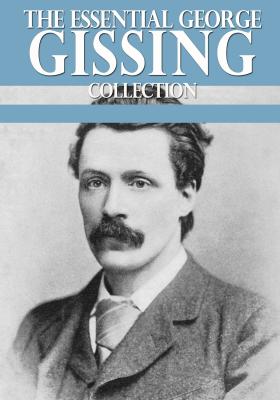

The Essential George Gissing Collection. George Gissing

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Essential George Gissing Collection |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | George Gissing |

| Жанр | Контркультура |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Контркультура |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781456613723 |

He passed into a large room, magnificently lighted by the sunshine, but very simply furnished. A small round table, two or three chairs and a piano were lost on the great floor, which had no carpeting, only a small Indian rug being displayed as a thing of beauty, in the very middle. There were no pictures, but here and there, to break the surface of the wall, strips of bright-coloured material were hung from the cornice. At the table, next the window, sat a man writing, also, as his lips showed, whistling a tune; and on the bare boards beside him sat a young woman with her baby on her lap, another child, of two or three years old, amusing itself by pulling her dishevelled hair.

"Here's your brother, Mr. Otw'y," yelled the little servant. "Give that baby to me, mum. I know what'll quoiet him, bless his little heart."

Alexander sprang up, waving his arm in welcome. He was a stoutish man of middle height, with thick curly auburn hair, and a full beard; geniality beamed from his blue eyes.

"Is it yourself, Piers?" he shouted, with utterance suggestive of the Emerald Isle, though the man was so loudly English. "It does me good to set eyes on you, upon my soul, it does! I knew you'd come. Didn't I say he'd come, Biddy?--Piers, this is my wife, Bridget the best wife living in all the four quarters of the world!"

Mrs. Otway had risen, and stood smiling, the picture of cordiality. She was not a beauty, though the black hair broad-flung over her shoulders made no common adornment; but her round, healthy face, with its merry eyes and gleaming teeth, had an honest attractiveness, and her soft Irish tongue went to the heart. It never occurred to her to apologise for the disorderly state of things. Having got rid of her fractious baby--not without a kiss--she took the other child by the hand and with pride presented "My daughter Leonora"--a name which gave Piers a little shock of astonishment.

"Sit down, Piers," shouted her husband. "First we'll have tea and talk; then we'll have talk and tobacco; then we'll have dinner and talk again, and after that whatever the gods please to send us. My day's work is done--_ecce signum_!"

He pointed to the slips of manuscript from which he had risen. Alexander had begun life as a medical student, but never got so far as a diploma. In many capacities, often humble but never disgraceful, he had wandered over Broader Britain--drifting at length, as he was bound to do, into irregular journalism.

"And how's the old man at home?" he asked, whilst Mrs. Otway busied herself in getting tea. "Piers, it's the sorrow of my life that he hasn't a good opinion of me. I don't say I deserve it, but, as I live, I've always meant to And I admire him, Piers. I've written about him; and I sent him the article, but he didn't acknowledge it. How does he bear his years, the old Trojan? And how does his wife use him? Ah, that was a mistake, Piers; that was a mistake. In marriage--and remember this, Piers, for your time'll come--it must be the best, or none at all. I acted upon that, though Heaven knows the trials and temptations I went through. I said to myself--the best or none! And I found her, Piers; I found her sitting at a cottage door by Enniscorthy, County Wexford, where for a time I had the honour of acting as tutor to a young gentleman of promise, cut short, alas!--'the blind Fury with the abhorred shears!' I wrote an elegy on him, which I'll show you. His father admired it, had it printed, and gave me twenty pounds, like the gentleman he was!"

There appeared a handsome tea-service; the only objection to it being that every piece was chipped or cracked, and not one thoroughly clean. Leonora, a well-behaved little creature who gave earnest of a striking face, sat on her mother's lap, watching the visitor and plainly afraid of him.

"Well," exclaimed Mrs. Otway, "I should never have taken you two for brothers--no, not even the half of it!"

"He has an intellectual face, Biddy," observed her husband. "Pale just now, but it's 'the pale cast of thought.' What are you aiming at, Piers?"

"I don't know," was the reply, absently spoken.

"Ah, but I'm sorry to hear that. You should have concentrated yourself by now, indeed you should. If I had to begin over again, I should go in for commerce."

Piers gave him a look of interest.

"Indeed? You mean that?"

"I do. I would apply myself to the science and art of money-making in the only hopeful way--honest buying and selling. There's something so satisfying about it. I envy even the little shopkeeper, who reckons up his profits every Saturday night, and sees his business growing. But you must begin early; you must learn money-making like anything else. If I had made money, Piers, I should be at this moment the most virtuous and meritorious citizen of the British Empire!"

Alexander was vexed to find that his brother did not smoke. He lit his pipe after tea, and for a couple of hours talked ceaselessly, relating the course of his adventurous life; an entertaining story, told with abundant vigour, with humorous originality. Though he had in his possession scarce a dozen volumes, Alexander was really a bookish man and something of a scholar; his quotations, which were frequent, ranged from Homer to Horace, from Chaucer to Tennyson. He recited a few of his own poetical compositions, and they might have been worse; Piers made him glow and sparkle with a little praise.

Meanwhile, Bridget was putting the children to bed and cooking the evening meal--styled dinner for this occasion. Both proceedings were rather tumultuous, but, amid the clamour they necessitated, no word of ill-temper could be heard; screams of laughter, on the other hand, were frequent. With manifest pride the little servant came in to lay the table; she only broke one glass in the operation, and her "Sure now, who'd have thought it!" as she looked at the fragments, delighted Alexander beyond measure. The chief dish was a stewed rabbit, smothered in onions; after it appeared an immense gooseberry tart, the pastry hardly to be attacked with an ordinary table knife. Compromising for the nonce with his teetotalism as well as his vegetarianism--not to pain the hosts--Piers drank bottled ale. It was an uproarious meal. The little servant, whilst in attendance, took her full share of the conversation, and joined shrilly in the laughter. Mrs. Otway had arrayed herself in a scarlet gown, and her hair was picturesquely braided. She ceased not from hospitable cares, and set a brave example in eating and drinking. Yet she was never vulgar, as an untaught London woman in her circumstances would have been, and many a delightful phrase fell from her lips in the mellow language of County Wexford.

When the remnants of dinner were removed, a bottle of Irish whisky came forth, with the due appurtenances. Then it was that Alexander, with pride in his eyes, made known Bridget's one accomplishment; she had a voice, and would presently use it for their guest's delectation. She was trying to learn the piano, as yet with small success; but Alexander who had studied music concurrently with medicine, and to better result, was able to furnish accompaniments. The concert began, and Piers, who had felt misgivings, was most agreeably surprised. Not only had Bridget a voice, a very sweet mezzo-contralto, but she sang with remarkable feeling. More than once the listener had much ado to keep tears out of his eyes; they were at his throat all the time, and his heart swelled with the passionate emotion which had lurked there to the ruin of his peace. But music, the blessed, the peacemaker (for music called martial is but a blustering bastard), changed his torments to ecstasy; his love, however hopeless, became an inestimable possession, and he seemed to himself capable of such great, such noble things as had never entered into the thought of man.

The crying of her baby obliged Bridget to withdraw for a little. Alexander, who had already made a gallant inroad on the whisky bottle, looked almost fiercely at his brother, and exclaimed:

"What do you day to _that_? Isn't that a woman? Isn't that a wife to be proud of?"

Piers replied with enthusiasm.

"Not long ago," proceeded the other, "when we were really hard up, she wanted me to let her try to earn money with her voice. She could, you know! But do you think I'd allow it? Sooner I'll fry the soles of my boots and make believe they're beefsteak!--Look at her, and remember her when you're seeking for a wife of your own. Never mind if you have to wait; it's worth it. When it comes to wives, the best or none! That's my motto."

In