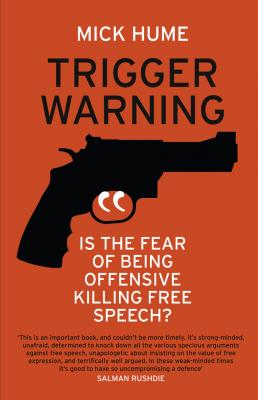

Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?. Mick Hume

Читать онлайн.| Название | Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech? |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Mick Hume |

| Жанр | Политика, политология |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Политика, политология |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780008126384 |

Faced with these attempts to impose new restrictions by narrowing the scope of free speech and broadening the exclusions, it is all the more important that we come out fighting for freedom of expression and holding the line between words and deeds.

But what about incitement? Inciting somebody to commit an offence is a crime. Offering an offensive opinion or inflammatory argument should not be. In a sense all arguments are ‘inciting’ – as in urging or provoking – somebody to do something, whether that means to change their opinion or the brand of coffee they drink. Those on the receiving end are still normally free to decide whether to do it. We should be very wary of criminalising speech so long as all that is being chucked about are words.

And what about offensive and hateful speech? These issues are addressed at length in this book. To begin with let us simply remember that in Western societies it is usually only those consensus-busting opinions branded offensive or unpalatable that need defending on the grounds of free speech. Nobody ever tries to ban speech for being too mundane. This is not a question of celebrating extremism or obnoxiousness. It is simply a matter of recognising that, when it comes to upholding the principle of free speech in practice, if we look after those opinions branded extreme, then the mainstream will look after itself.

Free speech is more important than hurt feelings. It is a sorry sign of the times that such a statement might seem outlandish to some. As recently as 1999 David Baugh, a leading black American civil liberties lawyer, defended a Ku Klux Klan leader who had been charged after a cross-burning, gun-toting rally. The attorney assured the jury that he was well aware that his client and the KKK hated black men like him. But that, Baugh argued, did not alter the racist’s free-speech rights: ‘In America, we have the right to hate. And we have the right to discuss it.’5

Baugh lost that cross-burning case on a point of law. Today he might be widely considered to have lost his mind. Yet he was right. In a civilised society, if we are talking about thoughts and words – however vitriolic – rather than violent deeds, all must be free to hate what or who they like, whether that means Muslims, Christians, bankers or Bono. To seek to ban the right to hate should be seen as no less an outrageous interference in the freedom to think for ourselves than a tyrant banning the right to love. The best way to counter hatreds and ideas we despise is not to try to bury them alive, but to drag them out into the light of day and debate them to the bitter end.

There is a good reason why it’s important to remember the meaning of both Free and Speech, however uncomfortable they might make us. Because the third thing we tend to forget about free speech is that it is the most important expression in the English language. Free speech is a key to unlock the door to much that we hold dear.

To borrow a phrase from the techies, free speech might be called the ‘killer app’ of civilisation, the core value on which the success of the whole system depends. It is worth reminding ourselves of what makes free speech so all-fired important that every other right or claim should have to get in line behind it.

Freedom of thought and of speech is part of what makes us unique as modern humans. The ability consciously to formulate and communicate ideas is one of the things that separates us above all from the animal kingdom. Free speech is the link connecting the individual and society. The essence of our modern humanity is to be able to think freely and rationally, but also to say what you think, to engage with and try to persuade (or be persuaded by) other people.

Free speech is the voice of the morally autonomous individual, nobody’s slave or puppet, who is free to make his or her own choices. It is the spirit of the age of modernity on full volume, first captured more than 350 years ago by the likes of Spinoza, the great Dutchman of the Enlightenment, who challenged the political and religious intolerance that dominated the old Europe and set the standard for a new world by declaring that ‘In a free state, every man may think what he likes and say what he thinks.’6

Free speech is not just about individual self-expression. It is the collective tool which humanity uses to develop its knowledge and understanding, to debate and decide on the truth of any scientific or cultural issue. Free speech is also the means by which we can bring democracy to life and fight over the future of society, through political engagement and the battle of ideas.

Free speech is not just a nice-sounding but impracticable idea, like ‘free love’. It has been an instrumental tool in the advance of humanity from the caves to something approaching civilisation. It is through the exercise of free speech and open debate that individuals and societies have been able to gain an understanding of where they want to go and why. The open expression of ideas and criticism has often proved the catalyst to the blossoming of creativity.

That’s why history often suggests that the freer speech a society has allowed, the more likely it is to have a climate where culture and science could flourish. Even before the modern age of Enlightenment, those past civilisations that we identify with an early flowering of the arts, science and philosophy had a disposition towards freedom of thought and speech that set them apart.

Ancient Greece, which laid foundations of civilisation in everything from architecture and theatre to mathematics and medicine, was the society where philosophers such as Socrates, Plato and Aristotle lit up the Athenian practice of free speech, or parrhesia. (Though even in democratic Athens, as we shall discuss later, Socrates was ultimately executed for taking free speech ‘too far’.) Several hundred years later the era now thought of as the Golden Age of Islamic civilisation, in the Middle East and Spain, was marked by important advances in the arts, education and science. Contrary to the image we might have of an Islamic caliphate today, many of those gains were made possible by a more tolerant attitude towards alternative ideas and foreign philosophies than prevailed under the conformism of the Christian empires of the Middle Ages.

The advance of free speech has been key to the creation of the freer nations of the modern world. Every movement struggling for more democracy and social change recognised the importance of public freedom of speech and of the press for articulating their aims and advancing their cause.

In 1649, at the time of the English Revolution and the execution of King Charles I, the radical Leveller movement petitioned parliament to end all state licensing of the press and allow everybody freedom to publish. Not because John Lilburne and the Levellers thought it would be a nice idea, but because these pioneers of the modern struggle for democracy understood the importance of press freedom and free speech to furthering the people’s fight for liberty. As the Levellers’ petition declared, ‘the liberty [of the press] appears so essential unto Freedom, as that without it, it’s impossible to preserve any Nation from being liable to the worst of bondage. For what may not be done to that people who may not speak or write, but at the pleasure of licensers?’7

Those fighting for American independence from British colonial rule in the eighteenth century also grasped that their democratic revolution required freedom of speech and debate to succeed. The wild pamphleteering and speech-making of the era played a central role in spreading ideas and information, in the forming of American revolutionary associations and forging of a new nation. In 1775, in one of the most famous speeches of the revolutionary era, Patrick Henry called upon his fellow delegates to the Virginia Convention to forget about going cap-in-hand to the Crown and instead stand and fight their oppressors – ‘Give me liberty or give me death!’ Henry spelled out the need for free speech to lay bare the truth of what was at stake, even if it risked offending or outraging his more moderate peers: ‘I consider it as nothing less than a question of freedom or slavery; and in proportion to the magnitude of the subject ought to be the freedom of the debate. It is only in this way that we can hope to arrive at truth, and fulfill the great responsibility which we hold to God and our country. Should I keep back my opinions at such a time, through fear of giving offence, I should consider