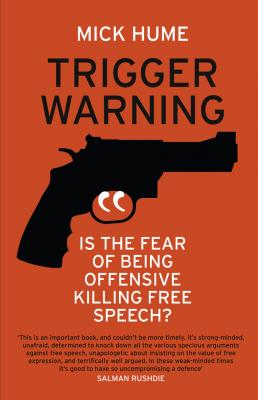

Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?. Mick Hume

Читать онлайн.| Название | Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech? |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Mick Hume |

| Жанр | Политика, политология |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Политика, политология |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780008126384 |

Even in the USA, land of the free and home of the First Amendment that gives constitutional protection to freedom of speech and of the press, the free-speech fraudsters were quick to distance themselves from Charlie Hebdo. President Barack Obama and secretary of state John Kerry both made bold statements in defence of free speech, Kerry winning plaudits for insisting that ‘no matter what your feelings were about [Charlie Hebdo], the freedom of expression that it represented is not able to be killed by this kind of act of terror’.13 The Obama administration was then criticised for failing to send any senior representative to the Paris march. However Laurent Léger, an investigative reporter at Charlie Hebdo and survivor of the attack, thought that was a more honest expression of the White House’s true attitude to free speech. ‘You have to be very happy he [Obama] didn’t come to the march in Paris,’ said Léger. ‘[His administration’s actions are] an absolute scandal.’14

Elsewhere in the US at one end of a Charlie-kicking consensus stood Bill Donohue, president of the Catholic League, a group that claims it is ‘motivated by the letter and spirit of the First Amendment’ in standing up for the right of Roman Catholics to speak their minds, regardless of what anybody else might think. Yet Donohue quickly dismissed the free-speech rights of the French cartoonists, asserting that ‘Muslims are right to be angry’ at the ‘insulting’ depictions of their prophet. He conceded that killing should not be tolerated before adding the punchline ‘but neither should we tolerate the kind of intolerance that provoked this violent reaction’, and concluded by criticising the editor of Charlie Hebdo for failing to understand ‘the role he played in his tragic death’. Clearly the spirit of the First Amendment would not be visiting atheist cartoonists.15

At the other end of the US consensus stood a clique of influential liberal and radical bloggers and tweeters, all seemingly keen to assure us that ‘these killings have nothing to do with freedom of speech or expression, regardless of how much our rulers and France’s try to cast them that way’.16 Kitty Stryker, self-styled ‘Geeky Porn Starlet/Lecturer/Presenter/Sex Critical Feminist’, summed it up for many. Although she is ‘generally pretty anti-censorship’ and ‘a big fan of art, and using humour to hopefully make people think and change their minds’, Kitty the feminist fighter draws the line at the likes of Charlie Hebdo, since ‘I do not believe that racist, homophobic language is satire’ (like other critics, she felt no need to explain how Charlie Hebdo had managed to be racist). Then she gets to the point: ‘I don’t think that shooting up the Charlie Hebdo offices was ethically Right with a capital R, OK? BUT I do think it’s understandable.’17 So to satirise Islam is unacceptable, but mass murder of satirists is understandable. And it has nothing to do with any attack on freedom of expression. Got that? Or are you a racist too?

One illustration of how far the tide might be turning against free speech in the US came when the departing ombudsman of National Public Radio declared ‘I am not Charlie’. In his ‘farewell blog posting’ Edward Schumacher-Matos wrote: ‘I do not know if American courts would find much of what Charlie Hebdo does to be hate speech unprotected by the Constitution but I know – hope? – that most Americans would.’18 What Schumacher-Matos seemingly ‘does not know’ is that there is no such thing as ‘hate speech unprotected by the Constitution’; offensive ‘hate speech’ is protected in the US by the First Amendment, as Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons certainly would be. Yet a leading media figure, who has not only worked as a journalist on top American newspapers for more than thirty years but even lectures on the First Amendment as a visiting professor at the prestigious Columbia University School of Journalism, apparently thinks otherwise, believing that Charlie Hebdo could – and should – be legally thrown to the wolves.

Surveying the different strands of this discussion in America, the headline on Anthony L. Fisher’s blog for Reason magazine captured the essential message of the free-speech frauds: ‘I’m all for free speech and murder is wrong. But …’19 Of course, everybody with a shred of humanity condemned the cold-blooded mass murder by Islamist gunmen. Well done. They had far less to say about the right of Charlie Hebdo or any other section of the Western press to publish whatever it believes to be true or just funny, regardless of whether it upsets Muslims or Catholics, Tories, socialists or transgender activists.

Asked what he thought of the rhetorical sympathy from the normally hostile European and international establishment, one surviving Charlie Hebdo cartoonist, 73-year old Bernard Holtrop, responded: ‘We puke on all these people who suddenly say they’re our friends.’ In the context that might seem harsh, but fair.20

The free-speech fraud around the Paris killings did not come out of the blue. It would be pleasant to imagine that the vocal ‘Je Suis Charlie’ reaction reflected the strength of support for freedom of speech and of the press in Europe and America. It would also be wrong. If there really was such solid support for free speech, it would not have taken the cold-blooded murder of cartoonists and journalists to prompt our politicians and public figures to mention it. The loud expressions of support for free speech have been so striking because they contrast with the everyday silence on the subject.

In normal circumstances we in the West now spend far more time discussing how to restrict and outlaw types of speech than how to defend and extend that precious liberty. Almost everybody in public life pays lip service to the principle of free speech. Scratch the surface, however, and in practice most will add the inevitable ‘But …’ to button that lip and put a limit on liberty. The ‘buts’ were out in force on both sides of the Atlantic and across the internet after Charlie Hebdo; to quote the American writer Andrew Klavan, it looked like ‘The Attack of the But-Heads’.21

This was the culmination of a steady loss of faith in freedom of speech and the ability of people to handle uncomfortable words or images. In recent years it has become fashionable not only to declare yourself offended by what somebody else says, but to use the ‘offence card’ to trump free speech and demand that they be prevented from saying it.

Charlie Hebdo itself was in the firing line of the war on offensive speech long before the gunmen burst into its editorial meeting. In 2007 the magazine was dragged into court under France’s proscriptive laws against ‘hate speech’ for publishing cartoons of Muhammad, in a case brought by the Paris Grand Mosque and the Union of French Islamic Organisations, with the undeclared support of some in high places. ‘This is not a trial against freedom of expression or against secularism’ was the free-speech fraudster’s protest from the Mosque’s lawyer, Francis Szpiner – who also happened to be a close ally of France’s President Jacques Chirac.22

Charlie Hebdo won that particular case, but others embraced the underlying principle of Europe’s hate-speech laws – that words and images which offend can be a suitable case for punishment – and expressed it in more forceful terms. In 2011 the satirical magazine’s offices were firebombed. There were no mass ‘Je Suis Charlie’ protests on that occasion. Indeed back then some observers were keen to spell out their contempt for Charlie’s right to offend. Time magazine