MREADZ.COM - много разных книг на любой вкус

Скачивание или чтение онлайн электронных книг.Blood and Capital

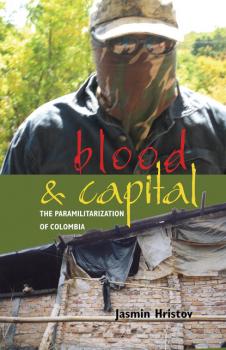

In Blood and Capital: The Paramilitarization of Colombia , Jasmin Hristov examines the complexities, dynamics, and contradictions of present-day armed conflict in Colombia. She conducts an in-depth inquiry into the restructuring of the state’s coercive apparatus and the phenomenon of paramilitarism by looking at its military, political, and legal dimensions. Hristov demonstrates how various interrelated forms of violence by state forces, paramilitary groups, and organized crime are instrumental to the process of capital accumulation by the local elite as well as the exercise of political power by foreign enterprises. She addresses, as well, issues of forced displacement, proletarianization of peasants, concentration of landownership, growth in urban and rural poverty, and human rights violations in relation to the use of legal means and extralegal armed force by local dominant groups and foreign companies. Hristov documents the penetration of major state institutions by right-wing armed groups and the persistence of human rights violations against social movements and sectors of the low-income population. Blood and Capita l raises crucial questions about the promised dismantling of paramilitarism in Colombia and the validity of the so-called demobilization of paramilitary groups, both of which have been widely considered by North American and some European governments as proof of Colombian president Álvaro Uribe’s advances in the wars on terror and drugs.

Under the Heel of the Dragon

The Turkic Muslims known as the Uighur have long faced social and economic disadvantages in China because of their minority status. Under the Heel of the Dragon: Islam, Racism, Crime, and the Uighur in China offers a unique insight into current conflicts resulting from the rise of Islamic fundamentalism and the Chinese government’s oppression of religious minorities, issues that have heightened the degree of polarization between the Uighur and the dominant Chinese ethnic group, the Han. Author Blaine Kaltman’s study is based on in-depth interviews that he conducted in Chinese without the aid of an interpreter or the knowledge of the Chinese government. These riveting conversations expose the thoughts of a wide socioeconomic spectrum of Han and Uighur, revealing their mutual prejudices. The Uighur believe that the Han discriminate against them in almost every aspect of their lives, and this perception of racism motivates Uighur prejudice against the Han. Kaltman reports that criminal activity by Uighur is directed against their perceived oppressors, the Han Chinese. Uighur also resist Han authority by flouting the laws—such as tax and licensing regulations or prohibitions on the use or sale of hashish—that they consider to be imposed on them by an alien regime. Under the Heel of the Dragon offers a unique insight into a misunderstood world and a detailed explanation of the cultural perceptions that drive these misconceptions.

Feminism and the Legacy of Revolution

In many Latin American countries, guerrilla struggle and feminism have been linked in surprising ways. Women were mobilized by the thousands to promote revolutionary agendas that had little to do with increasing gender equality. They ended up creating a uniquely Latin American version of feminism that combined revolutionary goals of economic equality and social justice with typically feminist aims of equality, nonviolence, and reproductive rights. Drawing on more than two hundred interviews with women in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and the Mexican state of Chiapas, Karen Kampwirth tells the story of how the guerrilla wars led to the rise of feminism, why certain women became feminists, and what sorts of feminist movements they built. Feminism and the Legacy of Revolution: Nicaragua, El Salvador, Chiapas explores how the violent politics of guerrilla struggle could be related to the peaceful politics of feminism. It considers the gains, losses, and internal conflicts within revolutionary women's organizations. Feminism and the Legacy of Revolution challenges old assumptions regarding revolutionary movements and the legacy of those movements for the politics of daily life. It will appeal to a broad, interdisciplinary audience in political science, sociology, anthropology, women's studies, and Latin American studies as well as to general readers with an interest in international feminism.

Peasants in Arms

Drawing on testimonies from contra collaborators and ex-combatants, as well as pro-Sandinista peasants, this book presents a dynamic account of the growing divisions between peasants from the area of Quilalí who took up arms in defense of revolutionary programs and ideals such as land reform and equality and those who opposed the FSLN. Peasants in Arms details the role of local elites in organizing the first anti-Sandinista uprising in 1980 and their subsequent rise to positions of field command in the contras. Lynn Horton explores the internal factors that led a majority of peasants to turn against the revolution and the ways in which the military draft, and family and community pressures reinforced conflict and undermined mid-decade FSLN policy shifts that attempted to win back peasant support.

Cracks in the Invisible

Stephen Kampa ’s poems are witty and restless in their pursuit of an intelligent modern faith. They range from a four-line satire of office inspirational posters to a lengthy meditation on the silence of God. The poems also revel in the prosodic possibilities of English’s high and low registers: a twenty–one line homage to Lord Byron that turns on three rhymes (one of which is “eisegesis”); a sestina whose end words include “sentimental,” “Marseilles,” and “Martian;” sapphics on the death of Ray Charles; and intricately modulated stanzas on the 1931 Spanish–language movie version of Dracula . Despite the metaphysical seriousness, there is always an undercurrent of stylistic levity — a panoply of puns, comic rhymes, and loving misquotations of canonical literature — that suggests comedy and tragedy are inextricably bound in human experience.

The Demographics of Empire

The Demographics of Empire is a collection of essays examining the multifaceted nature of the colonial science of demography in the last two centuries. The contributing scholars of Africa and the British and French empires focus on three questions: How have historians, demographers, and other social scientists understood colonial populations? What were the demographic realities of African societies and how did they affect colonial systems of power? Finally, how did demographic theories developed in Europe shape policies and administrative structures in the colonies? The essays approach the subject as either broad analyses of major demographic questions in Africa’s history or focused case studies that demonstrate how particular historical circumstances in individual African societies contributed to differing levels of fertility, mortality, and migration. Together, the contributors to The Demographics of Empire question demographic orthodoxy, and in particular the assumption that African societies in the past exhibited a single demographic regime characterized by high fertility and high mortality.

The Red Earth

Phu Rieng was one of many French rubber plantations in colonial Vietnam; Tran Tu Binh was one of 17,606 laborers brought to work there in 1927, and his memoir is a straightforward, emotionally searing account of how one Vietnamese youth became involved in revolutionary politics. The connection between this early experience and later activities of the author becomes clear as we learn that Tran Tu Binh survived imprisonment on Con Son island to help engineer the general uprising in Hanoi in 1945. The Red Earth is the first of dozens of such works by veterans of the 1924–45 struggle in Vietnam to be published in English translation. It is important reading for all those interested in the many-faceted history of modern Vietnam and of communism in the non-Western world.

In Step with the Times

The helmet-shaped mapiko masks of Mozambique have garnered admiration from African art scholars and collectors alike, due to their striking aesthetics and their grotesque allure. This book restores to mapiko its historic and artistic context, charting in detail the transformations of this masquerading tradition throughout the twentieth century. Based on field research spanning seven years, this study shows how mapiko has undergone continuous reinvention by visionary individuals, has diversified into genres with broad generational appeal, and has enacted historical events and political engagements. This dense history of creativity and change has been sustained by a culture of competition deeply ingrained within the logic of ritual itself. The desire to outshine rivals on the dance ground drives performers to search for the new, the astonishing, and the topical. It is this spirit of rivalry and one-upmanship that keeps mapiko attuned to the times that it traverses. In Step with the Times is illustrated with vibrant photographs of mapiko masks and performances. It marks the most radical attempt to date to historicize an African performative tradition.

Slavery and Reform in West Africa

A series of transformations, reforms, and attempted abolitions of slavery form a core narrative of nineteenth-century coastal West Africa. As the region's role in Atlantic commercial networks underwent a gradual transition from principally that of slave exporter to producer of “legitimate goods” and dependent markets, institutions of slavery became battlegrounds in which European abolitionism, pragmatic colonialism, and indigenous agency clashed. In Slavery and Reform in West Africa , Trevor Getz demonstrates that it was largely on the anvil of this issue that French and British policy in West Africa was forged. With distant metropoles unable to intervene in daily affairs, local European administrators, striving to balance abolitionist pressures against the resistance of politically and economically powerful local slave owners, sought ways to satisfy the latter while placating or duping the former. The result was an alliance between colonial officials, company agents, and slave-owning elites that effectively slowed, sidetracked, or undermined serious attempts to reform slave holding. Although slavery was outlawed in both regions, in only a few isolated instances did large-scale emancipations occur. Under the surface, however, slaves used the threat of self-liberation to reach accommodations that transformed the master-slave relationship. By comparing the strategies of colonial administrators, slave-owners, and slaves across these two regions and throughout the nineteenth century, Slavery and Reform in West Africa reveals not only the causes of the astounding success of slave owners, but also the factors that could, and in some cases did, lead to slave liberations. These findings have serious implications for the wider study of slavery and emancipation and for the history of Africa generally.

Paper Sons and Daughters

Ufrieda Ho’s compelling memoir describes with intimate detail what it was like to come of age in the marginalized Chinese community of Johannesburg during the apartheid era of the 1970s and 1980s. The Chinese were mostly ignored, as Ho describes it, relegated to certain neighborhoods and certain jobs, living in a kind of gray zone between the blacks and the whites. As long as they adhered to these rules, they were left alone. Ho describes the separate journeys her parents took before they knew one another, each leaving China and Hong Kong around the early 1960s, arriving in South Africa as illegal immigrants. Her father eventually became a so-called “fahfee man,” running a small-time numbers game in the black townships, one of the few opportunities available to him at that time. In loving detail, Ho describes her father’s work habits: the often mysterious selection of numbers at the kitchen table, the carefully-kept account ledgers, and especially the daily drives into the townships, where he conducted business on street corners from the seat of his car. Sometimes Ufrieda accompanied him on these township visits, offering her an illuminating perspective into a stratified society. Poignantly, it was on such a visit that her father—who is very much a central figure in Ho’s memoir—met with a tragic end. In many ways, life for the Chinese in South Africa was self-contained. Working hard, minding the rules, and avoiding confrontations, they were able to follow traditional Chinese ways. But for Ufrieda, who was born in South Africa, influences from the surrounding culture crept into her life, as did a political awakening. Paper Sons and Daughters is a wonderfully told family history that will resonate with anyone having an interest in the experiences of Chinese immigrants, or perhaps any immigrants, the world over.