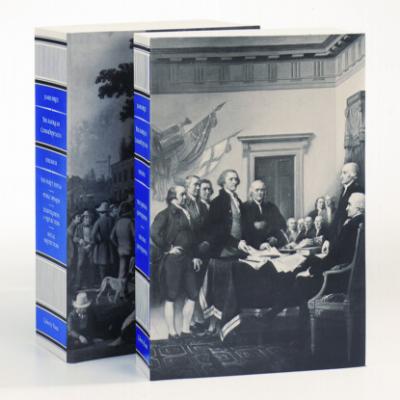

The American Commonwealth. Viscount James Bryce

Читать онлайн.| Название | The American Commonwealth |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Viscount James Bryce |

| Жанр | Историческая литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Историческая литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781614871217 |

The secretary of the treasury is minister of finance. His function was of the utmost importance at the beginning of the government, when a national system of finance had to be built up and the federal government rescued from its grave embarrassments. Hamilton, who then held the office, effected both; and the work of Gallatin, who served under Jefferson, was scarcely less important. During the War of Secession, it became again powerful, owing to the enormous loans contracted and the quantities of paper money issued, and it remains so now, because it has the management (so far as Congress permits) of the currency and the national debt. The secretary has, however, by no means the same range of action as a finance minister in European countries, for as he is excluded from Congress, although he regularly reports to it, he has nothing directly to do with the imposition of taxes, and very little with the appropriation of revenue to the various burdens of the state.6

The secretary of the interior is far from being the omnipresent power which a minister of the interior is in France or Italy, or even a home secretary in England, since nearly all the functions which these officials discharge belong in America to the state governments or to the organs of local government. He is chiefly occupied in the management of the public lands, still of immense value, despite the lavish grants made to railway companies, and with the conduct of Indian affairs, a troublesome and unsatisfactory department, which was long a reproach to the United States, and may from time to time become so, till the Indians themselves disappear or have been civilized. Patents and pensions, the latter a source of great expense and abuse, also belong to his province, as do the meteorological office, the geological survey, and the reclamation office.

The duties of the secretaries of war, of the navy, of agriculture, of commerce, of labour, and of the postmaster general may be gathered from their names. But the attorney general is sufficiently different from his English prototype to need a word of explanation. He is not only public prosecutor and standing counsel for the United States, but also to some extent what is called on the European continent a minister of justice. He has a general oversight—it can hardly be described as a control—of the federal judicial departments, and especially of the prosecuting officers called district attorneys, and executive court officers, called United States marshals. He is the legal adviser of the president in those delicate questions, necessarily frequent under the Constitution of the United States, which arise as to the limits of the executive power and the relations of federal to state authority, and generally in all legal matters. His opinions are frequently published officially, as a justification of the president’s conduct, and an indication of the view which the executive takes of its legal position and duties in a pending matter.7 Some of them have indeed a quasi-judicial authority, for when a department requests his opinion on a question of law, as for instance, regarding the interpretation of a statute, that opinion is deemed authoritative for the officials, although, of course, a judgment of a federal court would upset it. His power to institute or abstain from instituting prosecutions under federal acts is also a function of much moment. The attorney general is always a lawyer of eminence, though not necessarily in the front rank of the profession, for political considerations have much to do with determining the president’s choice.8

The creation of the departments of commerce and of labour was an evidence of that extension of the functions of government into new fields which is no less remarkable in the United States than it is in Europe. Among the duties of the former are the supervision of corporations (other than railroads) doing interstate business, lighthouses, the coast and geodetic survey, merchant shipping, the census, and trade statistics. The latter has within its sphere the administration of the immigration laws.

It will be observed that from this list of ministerial offices several are wanting which exist in Europe. Thus there is no minister of education, because that department of business belongs to the several states;9 no minister of public worship, because the United States government has nothing to do with any particular form of religion; no minister of public works, because grants made for this purpose come direct from Congress without the intervention of the executive, and are applied as Congress directs.10 Neither was there, till the Philippine Isles and Puerto Rico were acquired, any colonial office. Since that date (1899) a Bureau of Insular Affairs has been established and placed under the War Department, to take charge of these dependencies. Much of the work which in Europe would devolve on members of the administration falls in America to committees of Congress, especially to committees of the House of Representatives. This happens particularly as regards taxation, public works, and the management of the Territories, for each of which matters there exists a committee in both houses. Some controversy has arisen in Washington regarding the respective precedence of cabinet ministers and of senators. The point is naturally of more importance as regards the wives of the claimants than as regards the claimants themselves.

The respective positions of the president and his ministers are, as has been already explained, the reverse of those which exist in the constitutional monarchies of Europe. There the sovereign is irresponsible and the minister responsible for the acts which he does in the sovereign’s name. In America the president is responsible because the minister is nothing more than his servant, bound to obey him, and independent of Congress. The minister’s acts are therefore legally the acts of the president. Nevertheless the minister is also responsible and liable to impeachment for offences committed in the discharge of his duties. The question whether he is, as in England, impeachable for giving bad advice to the head of the state has never arisen, but upon the general theory of the Constitution it would rather seem that he is not, unless of course his bad counsel should amount to a conspiracy with the president to commit an impeachable offence. In France the responsibility of the president’s ministers does not in theory exclude the responsibility of the president himself, although practically it makes a great difference, because he, like the English Crown, acts through ministers supported by a majority in the Chamber.

So much for the ministers taken separately. It remains to consider how an American administration works as a whole, this being in Europe the most peculiar and significant feature of the parliamentary or so-called “cabinet” system.

In America the administration does not work as a whole. It is not a whole. It is a group of persons, each individually dependent on and answerable to the president, but with no joint policy, no collective responsibility.11

When the Constitution was established, and George Washington chosen first president under it, it was intended that the president should be outside and above party, and the method of choosing him by electors was contrived with this very view. Washington belonged to no party, nor indeed, though diverging tendencies were already manifest, had parties yet begun to exist. There was therefore no reason why he should not select his ministers from all sections of opinion. As he was responsible to the nation and not to a majority in Congress, he was not bound to choose persons who agreed with the majority in Congress. As he, and not the ministry, was responsible for executive acts done, he had to consider, not the opinions or affiliations of his servants, but their capacity and integrity only. Washington chose as secretary of state Thomas Jefferson, already famous as the chief draftsman of the Declaration of Independence, and as attorney general another Virginian, Edmund Randolph, both men of extreme democratic leanings, disposed to restrict the action of the federal government within narrow limits. For secretary of the treasury he selected Alexander Hamilton of New York, and for secretary of war Henry Knox