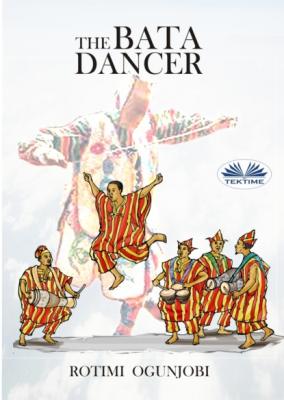

The Bata Dancer. Rotimi Ogunjobi

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Bata Dancer |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Rotimi Ogunjobi |

| Жанр | Зарубежное фэнтези |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Зарубежное фэнтези |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9788835416302 |

Ayangalu arrived at noon in a large town. He had washed himself at the river, and his robe was now wrapped around him, only up to the shoulder. He walked resolutely, he walked with purpose.

This day, was coronation day at the town. A new king was being crowned and everywhere there was singing and dancing. The musician played on simple instruments hewn from dried huge gourds. They played melodies on the hard, dry back of their igba - huge bowls cut from the gourds, which they beat with little dry sticks. . Some played accompaniments on their sekere: whole gourds, hollowed, dried and wrapped in netting strung with beads and corral shell for percussion. It was a joyous event, and as it is said, the sekere does not attend a gathering of mourners. The musicians played skilfully and joyfully.

The music was good, but not fit for majesty, Ayangalu would pensively observe. He sat and watched, for long. He shared of the abundance of food, and drank of the abundance of wine from the palm tree; and at dusk he retired to the edge of the town, into a bed of gathered leaves. Ayangalu could no more remember where he came from nor how far he had travelled; these were no more important. He knew he had reached his place of destiny. He slept happily

The next day, Ayangalu rose to a pressing purpose. He discovered not too far away from his night bed, a mature tree. He cut it down, cut a piece of the soft trunk, and hollowed out a cylinder. One of the open ends, he covered with the flayed skin of a wild boar. Satisfied with his handiwork, he set it in the sun to dry.

At evening, when the musicians again gathered with the congregation to make merry and to rejoice with the king, Ayangalu picked up his handiwork and joined with them. And as the king stood to dance, Ayangalu straddled his own instrument and with his palms beat an accompaniment to the regular orchestra of igba and sekere. The hollow throb of the beat mellowed down the high-pitched chatter of the other instruments. Together, they produced a more pleasant music, kinder to the ear, friendlier to the dancing legs. The king was joyful; he showered Ayangalu with praise and with money. The folks were also filled with amazement at the skill of the stranger who came with the strange instrument of which he clearly was a master.

“Stranger, what is the name of this thing?” the king was curious enough to ask.

“Ilu “, Ayangalu answered. “The name is ilu – the thing which is beaten. I also call it drum”

The coronation was a seven day event. Every evening, Ayangalu came with his drum, and played for the pleasure of the king. And in appreciation, the folks of the town daily fed him till he could eat no more and gave him wine to drink till he every night stumbled away to his bed.

The hunter saw Ayangalu playing his drum in the midst of the merrymakers. He saw Ayangalu where he slept every night uncovered under the moon and the stars. The hunter recognised Ayangalu, not because of his ageless face which he never previously saw, but because of the coarse robe, the musty smell of which refused to be dismissed from memory.

“Come sleep in my house.” the hunter suggested. But Ayangalu would not. He built a hut at the edge of the town and from there crafted more drums of several shapes and timbre. And whenever and wherever there was celebration, Ayangalu would pick up his drum, any of his many drums which had the right voice for each occasion. And all would come from near and far to dance to the merry beat of Ayangalu’s drum.

“Come teach me this wonderful craft”, the hunter came to him, and also did many other of the young men. And they daily gathered at the front of Ayangalu’s hut; and he taught them the mysteries of the drum. Again, the hunter came to Ayangalu and said:

“I shall present you a wife; a beautiful maiden of your choice. And of her you shall have children, many of them, so that your wisdom should remain forever amongst us in these lands”. But Ayangalu, smiled, slowly shook his head and replied:

“I have no child. I do not want a child. You shall all be my children, and Ayan shall be your names”

And so took the hunter the name of Ayantunji and another man, the name of Ayandele, and yet another took the name of Ayanniyi, and so it became that each of the disciples of the drum were named in such a fashion. Day after day, the heart-rousing sounds of drumming came to be heard from all over the town, as the followers of Ayangalu with child-like glee and abandon celebrated their new proficiency. One morning, the disciples of the drum came as before to gather before their master, but in vain they called and searched, for Ayangalu was nowhere again to be found.

Time passed. Drummers for generations thereafter made drums of their own and each after their own names. The drummer, whose name was Dundun, made himself drums, shaped like an hourglass. Around the rims of the skin-covered ends he fixed little brass bells which jingled merrily while he played his instrument. His drums were made for merrymaking of all and sundry. The drummer whose name was Gbedu made himself a drum, to which all else but kings, lieutenants and kingmakers were forbidden to dance. Bata made his drums from trees cut from the edge of the well-travelled roads, and which had therefore heard much of conversation and thus were consequently wiser. The voice of the drum of Bata came out shrill and harsh, demanding, commanding to be matched in zest and spirit by the able-bodied dancer. Some made drums for merrymaking, some made drums for ceremonies, and some made drums for the pleasure of the deities.

And there came a time when the Immortals, the Orisa were gathered to be entertained. And the drummer and their drums congregated also and came each after another to display their dexterity and their voices before the keepers of the sacred shrines. They brought drums in their different shapes, in their different sizes, in the different voices. They knew nevertheless that the Orisa were selective, each discerning of the instruments to be brought before them. The drummers knew that even though the deities loved to dance, each danced with a regal individuality. And of their dances there were four hundred and one variations, as many as there were of the Orisa.

They knew nevertheless that not one Orisa rejected or was ever displeased by the several drums of Dundun, from the gudugudu to the kerikeri. The ensemble of Dundun came always with happy instruments. They were fashioned after the pleasure of the entire pantheon of Orisa. But the Orisa, also of the many drums each selected favourites. Obatala, in whose hands were all the wisdoms of the entire world, favoured the deep-throated throb of the Igbin drum. Osun, custodian of the mysteries of procreation was ever thrilled by the seductive serenading of the Bembe drum. And whenever Sango , the violent one heard the frenetic beat of Bata, his delight came so great that the earth trembled with thunder and lighting criss-crossed the sky like jagged javelins hurled by clouds at one another in fierce battles of pleasure.

CHAPTER 1

Yomi Bello walked slowly and carefully as if he feared that he would stumble and fall. His limp from a childhood injury, normally slight and barely noticeable, this afternoon appeared like a major impediment even on this flat concrete roadway. His mind was occupied by an incongruous mixture of emotions; he felt sadness, relief, excitement and even a bit of fear. Most important was that, as the warm rays of the sun stung his face, for the first time in more than seven years, he felt delightfully free.

Yomi walked away from the building that housed the Ministry of Culture at the government secretariat and towards the car park where he left his car. Saying goodbye was never one of the things he knew how to do well. He had just left the office of his friend, Debola Adebayo who was Director in this government department, and also in charge of the Heritage Theater, a cultural project where Yomi had been for eight years employed as a scriptwriter.

His friend, Debola, was even sadder when Yomi came to his office to say goodbye.

“Never mind Yomi; I am sure the Theater will be back in a few more months”, Debola assured.

“It’s been down for more than two years”, Yomi reminded.

“I know. Government does not have the money to support it anymore, but I”ve been talking to some other sponsors and I am very hopeful”, Debola told him.