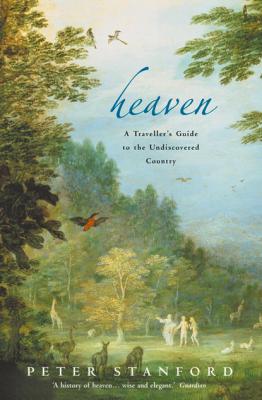

Heaven: A Traveller’s Guide to the Undiscovered Country. Peter Stanford

Читать онлайн.| Название | Heaven: A Traveller’s Guide to the Undiscovered Country |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Peter Stanford |

| Жанр | Зарубежная эзотерическая и религиозная литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Зарубежная эзотерическая и религиозная литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780007439652 |

Set against such worldly belief systems, Buddhism had a strong mystical appeal when it first came to China. Its doctrines of individual liberation stood in contradiction to the more corporatist leanings of Confucianism and Taoism. There has never been one, single form of Chinese Buddhism, but a whole variety of alternatives, some developing highly disciplined monastic schools – for example in Tibet – others straying into magic and sorcery.

Two of these are of particular interest because they developed more explicit ideas of paradise than those of Buddha himself: Ching-tu or ‘Pure Land’ Buddhism was formulated in China by T’an-luan (AD 476–542). Devotees believe that they reach an equivalent to nirvana not only through their own powers and their own interior journey towards transcendence but also through devotion to and dependence upon a later incarnation of the Buddha, Amida Buddha, ‘the Lord of Light’ who presides over a pure land or land of bliss. The modification to encompass a more defined and judgemental deity means that paradise, as that deity’s court, also is necessarily more precise, as set out in the Sukhavativyuha Sutra:

Breezes blow spontaneously, gently moving these bells [that hang from trees in the four corners of the land], which swing gracefully. The breezes blow in perfect harmony. They are neither hot nor cold. They are at the same time calm and fresh, sweet and soft. They are neither fast nor slow. When they blow on the nets and the many kinds of jewels, the trees emit the innumerable sounds of the subtle and sublime Dharma [the principles behind the law] and spread myriad sweet and fine perfumes. Those who hear these sounds spontaneously cease to raise the dust of tribulation and impurity. When the breezes touch their bodies, they all attain a bliss comparable to that accompanying a monk’s attainment of the samadhi of extinction.

Moreover, when they blow, these breezes scatter flowers all over, filling this buddha-field. These flowers fall into patterns, according to their colours, without ever being mixed up. They have delicate hues and strong fragrance. When one steps on these petals, the feet sink four inches. When one lifts the foot, the petals return to their original shape and position.

(from Land of Bliss, Luis Gomez)

This Pure Land is thought to exist in a particular place – beyond the sunset in the West – but it still remains, for all the detail, at heart a state of mind, the end point in the cycle of reincarnation achieved by those who raise themselves mentally and spiritually above day-to-day existence. There may be more of a focus on Ching-tu than on other forms of Buddhism, but still there is none of the resurrection hope that fuels monotheistic heavenly visions.

Tibet was slower than China to develop an interest in Buddhism. Its ancient creed, Bon, was an earthbound spirituality, with deities who were attuned to the landscape. The god Za, for instance, produced hailstones and lightning to damage the crops. This magical link between land and the gods was a practical support for a farming people, and they saw no need to replace it. Buddhism, when it came, had to be imposed on them by their rulers. In the eighth century King Trisongdetsen hoped that Buddhism would be a way of encouraging a higher, more sophisticated and more philosophical culture among his people. When it eventually took root, Tibetan Buddhism held fast to the essential beliefs of Buddha, though it modified them, resorting, for instance, to Vajrayana, a form of meditation undertaken by students and teachers which has the power to bring the enlightened state into everyday life.

Tibetan Buddhism, more so than its near relatives, has traditionally had a strong sense of the closeness of death. The Indian master Padmasambhava, ‘the Lotus-Born’, is credited as the founder of Tibetan Buddhism (though some doubt he ever existed), and he is said to have abandoned palaces to live on the charnel ground, a cemetery where dead bodies were traditionally left to rot as a reminder to the faithful of the unimportance of the human form and also because of a lack of fuel with which to burn corpses. Padmasambhava found the charnel ground an excellent place for meditation on the importance of letting go of your ego and your attachment to this life. It provided, he believed, the impetus to see beyond life and death to ultimate enlightenment.

Tibetan Buddhism followed his emphasis on death. In the Tibetan Book of the Dead, much is made of bardo, or the often frightening gap that opens up when you lose touch with life. It is a transitional state, but covers both the approach of physical death and the preface to enlightenment which can happen while you are alive. The two are seen as one. Bardo is dominated by a brilliant light which allows the true nature of the mind to be seen in all its glory. For those who can take this vision, liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth is at that moment possible, but the Book of the Dead teaches that most people in this transitory state are too confused and so are swept along, via a path of sometimes terrifying, sometimes peaceful, visions to new birth.

Even they offer you a chance to gain understanding, as long as you remain vigilant and alert. A few days after death, there suddenly emerges a subtle illusory dream-body also known as the ‘mental body’. It is impregnated with the after-effects of your past desires, endowed with all sense-faculties, and has the power of unimpeded motion. It can go through rocks, hills, boulders and walls, and in an instant it can traverse any distance. Even after the physical sense-organs are dissolved, sights, sounds, smells, tastes and touches will be perceived, and ideas will be formed. These are the result of energy still residing in the six kinds of consciousness, the after-effects of what you did with your body and mind in the past. But you must know that all you perceive is a mere vision, a mere illusion, and does not reflect any really existing objects.

(Buddhist Scriptures, translated by Edward Conze)

This is followed by visions, by being confronted by a deity with the ‘shining mirror’ of karma, and by the dawning of ‘the six places of rebirth’. Setting out, dazed and desirous on a walk across deserts of burning sands, tormented by beasts who are half human, half animal and by hurricanes, you head for a place of refuge.

Everywhere around you, you will see animals and humans in the act of sexual intercourse. You envy them, and the sight attracts you. If your karmic coefficients destine you to become a male, you feel attracted to females and you hate the males you see. If you are destined to become a female, you will feel love for the males and hatred for the females you see. Do not go near the couples you see, do not try to interpose yourself between them, do not try to take the place of one of them. The feeling which you would then experience would make you faint away, just at the moment when egg and sperm are about to unite. And afterwards you will find that you have been conceived as a human being or as an animal.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead symbolises the penultimate one of the five alternative explanations of what happens after death. Complete oblivion was to be posited later, with the advance of science and reason, and so, long before the birth of Christianity, a choice of four beliefs existed with a shadowy afterlife in the earliest civilisations; immortality of the soul as preached by the Greeks; resurrection of body and soul, increasingly popular within Judaism; and reincarnation, the evolution to a higher form of life in this life and the constant cycle of death and rebirth found in most Eastern traditions.

CHAPTER THREE But Not Life as We Know it

There is a school of thought which claims Jesus was an Essene, and that he is the ‘righteous teacher’ referred to in the Dead Sea Scrolls. However, the case remains unproven and is scorned by many eminent religious historians. What is true is that in Jesus’ pronouncements on heaven and afterlife recorded in the Gospels, he shows more than a touch of Essene influence. Generally, early Christian ideas about heaven broadly mirror the contemplative Essenes in that they are little concerned with the fate of Israel, or indeed with anything to do with this world, being almost exclusively focused on a personal experience of the divine be it compensation for whatever ills have befallen individuals in their earthly lives, or, more simply, anticipation of the promised all-consuming experience in death which will wipe out all that has gone before.

Christianity distanced itself from its Jewish inheritance, in that heaven was seen as being exclusively with God in the hereafter, with no ongoing ties to this world. Gradually, over the centuries, the new religion moved