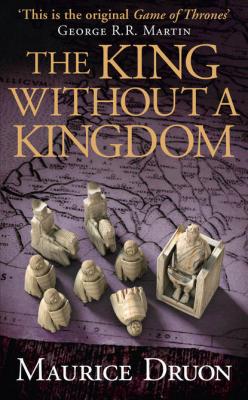

The King Without a Kingdom. Морис Дрюон

Читать онлайн.| Название | The King Without a Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Морис Дрюон |

| Жанр | Историческая литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Историческая литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780007492275 |

It was also in Limoges that I began my studies in astrology. For this reason: the two sciences most necessary for the exercise of authority in government are indeed the science of law and the science of the stars. The former teaches us the laws that govern the relationships between men and the obligations they have towards each other, or with the kingdom, or with the Church, while the latter gives us knowledge of the laws that govern the relationships men have with Providence. The law and astrology; the laws of the earth, the laws of the heavens. I say that there is no denying it. God brings each of us into the world at the hour He so wishes, and this exact time is written on the celestial clock, which by His good grace, He has allowed us to read.

I know there are certain believers, wretched men, who deride astrology as a science because it abounds in charlatans and peddlers of lies. But that has always been the way; the old books tell us that paltry fortune-tellers and false wise men, hawking their predictions, were denounced by the ancient Romans and by the other ancient civilizations; that never stopped them seeking out the art of the good and the just observers of the celestial sphere, who often practised their skills in sacred places. Just so, it is not thought wise to close down all the churches because there exist simoniacal or intemperate priests.

I am so pleased to see that you share my opinions on this matter. It is the humble attitude proper for the Christian before the decrees of Our Lord, the Creator of all things, who stands behind the stars.

You would like to … but of course, my nephew, I will be delighted to do yours. Do you know your time of birth? Ah! That you will need to find out; send someone to your mother and ask her to give you the exact time of your first cry. Mothers remember such things.

As far as I am concerned, I have never received anything but praise for my practice of astral science. It enabled me to give useful advice to those princes who deigned to listen to me, and also to know the nature of any man I found myself up against and to be wary of those whose fate was adverse to mine. Thus I knew from the beginning that Capocci would be an opponent in all things, and I have always distrusted him. It is the stars that have guided me to the successful completion of a great many negotiations, and the making of as many favourable arrangements, such as the match for my sister in Durazzo, or the felicitous marriage of Louis of Sicily; and the grateful beneficiaries swelled my fortune accordingly. But first of all, it was to John XXII (may God preserve him; he was my benefactor) that this science was of the most invaluable service. Because Pope John himself was a great alchemist and astrologian; knowing of my devotion to the same art, and the distinction I had attained in it, impelled him to show increased favour for myself and inspired him to listen to the wishes of the King of France and make me cardinal at the age of thirty, which is a most unusual thing. And so I went to Avignon to receive my galero. You know how such a thing takes place. Don’t you?

The pope gives a grand banquet for the entrance of the new recruit to the Curia, to which he invites all the cardinals. At the end of the meal, the pope sits on his throne, poses the galero upon the head of the new cardinal, who remains kneeling and kisses first his foot, then his lips. I was too young for John XXII … he was eighty-seven at that time … to call me venerabilis frater; so he chose to address me with a dilectus filius. And before inviting me to stand up, he whispered in my ear: ‘Do you know how much your galero cost me? Six pounds, seven sols and ten deniers.’ It was in the way of that pontiff to humble you, precisely at that moment when you felt the most proud, always having a word of mockery for delusions of grandeur. Of all the days of my life there is not a single one of which I have kept a sharper memory. The Holy Father, all withered and wrinkled under his white zucchetto, which hugged his cheeks … It was the fourteenth of July of the year 1331 …

Brunet! Have them stop my palanquin! I am going to stretch my legs a little, with my nephew, while they brush off these crumbs. This is a flat stretch, and we are graced with a ray of sunlight, you will pick us up further on. Only twelve will escort me; I would like a little peace … Hail, Master Vigier … hail, Volnerio … hail, du Bousquet … may the peace of God be with you all, my sons, my good servants.

The Beginnings of the King they call The Good

KING JOHN’S BIRTH chart? Indeed, I know it; I have turned my attention to it on many an occasion … Had I foreseen it? Of course, I had foreseen everything; that is why I worked so hard to prevent this war, knowing full well that it would be disastrous for him, and consequently disastrous for France. But try and get a man to understand reason, particularly a king whose stars act as a barrier precisely to understanding and to reason itself!

At birth, King John II saw Saturn reach its highest point in the constellation of Aries, at the centre of the heavens. This is a dire configuration for a king, one that foretells deposed sovereigns, reigns that come to a natural end all too hastily or that tragic events cut short. Add to that, his moon rising in the sign of Cancer, itself lunar by nature, thus marking an overly feminine disposition. Finally, and to give you just the most striking features, the traits that are most obvious to any astrologer, there is a problematic grouping of the Sun, Mercury and Mars which are closely linked in Taurus. There you have a most threatening sky making up an unbalanced man, masculine and even of a thickset appearance, but for whom all that should be virile is as if castrated, up to and including understanding; at the same time a brutal and violent man, possessed by dreams and secret fears that provoke sudden and murderous fits of rage, incapable of listening to advice or of the slightest self-control, hiding his weaknesses under an exterior of grand ostentation; yet at the core, a fool, the exact opposite of a conqueror, his soul the opposite of the soul of a commander.

For certain people it would seem that defeat was their main preoccupation, they have a secret craving for it, and will not rest until they have found it. Defeat pleases the depths of their souls, the spleen of failure is their favourite beverage, as the mead of victory is to others; they long for subordination, and nothing suits them better than to contemplate themselves in a state of imposed submission. It is a great misfortune when such predispositions hang over the head of a king from the moment of his birth.

So long as John II had been Monseigneur of Normandy, living under the thumb of a father he didn’t care for, he had seemed an acceptable prince, and the ignorant believed his reign would be a happy one. For that matter, the people and even the court, forever inclined to succumb to delusion, always expect the new king to be better than his predecessor, as if novelty intrinsically carried miraculous virtue. No sooner did John have the sceptre in his hands than he began to show his true colours; the stars and his nature, in their unfortunate alliance, were bent on defeat.

He had only been king ten days when Monsieur of Spain, in the month of August 1350, was defeated at sea, off the coast of Winchelsea, by King Edward III. Charles of Spain was in command of a Castilian fleet, and our Sire John was not responsible for the expedition. However, since the victor was from England, and the vanquished a very close friend of the King of France, it was a poor start for the French monarch.

The coronation took place at the end of September. By then Monsieur of Spain had returned, and in Rheims they showed the vanquished man a good deal of sympathy, thus consoling him in his defeat.

In November the constable of France, Raoul II of Brienne, Count of Eu, returned to France. Though he had been taken prisoner four years earlier by King Edward, as a captive he had been free to do almost as he pleased, even to travel between the