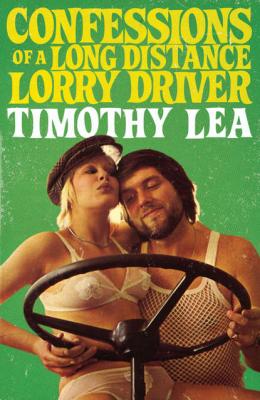

Confessions of a Long Distance Lorry Driver. Timothy Lea

Читать онлайн.| Название | Confessions of a Long Distance Lorry Driver |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Timothy Lea |

| Жанр | Классическая проза |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Классическая проза |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780007530212 |

This may well be the moment to say goodbye. Olga was not amused when I told her that I thought the Red Square was a geezer called Brezhnev and it is clear that there is another side to her nature that I have not been fully exposed to. Life with Olga would not purely be a question of getting tossed off in Rostov.

Whilst my fair companion snuggles closer to her wodka bottle I slip into the threads provided by Boris. They may go down a bomb in the Stalingradski Prospect but I don’t reckon that they are going to pull a lot of birds down the baths hall. Still, that is not my number one problem at the moment. Blowing what I hope is a farewell kiss to the toast of the Neva, I ease open the cabin door and stick my hooter out into the corridor. Not a sausage. Less sign of a human being than there is of a knot in a Scotsman’s used french letter – at least, that is, until I start walking down the corridor. Then Boris’s boots appear down the steps, closely followed by the rest of his body. He eyes me suspiciously and the nozzle of his submachine-gun starts giving percy palpitations.

‘There you are!’ I say in a flash of creative desperation. ‘I’ve been looking for you everywhere. Olga wants you.’

The way I say ‘wants you’ must make it clear to him that she is not seeking someone to unblock a stuffed up plughole.

‘Me?’ Boris’s chest swells visibly. I don’t know about the rest of him, I don’t look.

‘She’s waiting for you in the cabin.’ I just have time to flatten myself against the wall before Boris charges past. Cupid Lea they call me.

I don’t hang about but canter up the steps and stick my bonce above deck level. Still no sign of anyone. I can hear the strain – and it is a strain, make no mistake about it – of an old Russian folk tune coming from the front of the boat. The crew must be having a musical evening. Good luck to them. Over to the rail I go and look over the side. As if to signal my good fortune the moon comes out and there, shimmering beside my reflection, is the outline of a dinghy. I take another quick glance about me and slip over the side. Fortunately, I manage to cling on to a rope before I do myself a serious injury. A few moments dangerous dangling and my feet scrabble against the side of the dinghy and manoeuvre it beneath me – it’s not getting too exciting for you is it? Good. I wouldn’t like to think that I was doing Alistair MacLean out of a living. Anyway, there I am, poised over the dinghy. The strength in my arms gives out and I tumble into the bottom of the boat. For a moment, it rocks alarmingly and then settles down to tap angrily against the side of the larger vessel. Quickly, I undo the piece of rope at the sharp end, and push off with one of the oars.

Free! What an evening for my treasure trove of memories. The dinghy drifts down the side of the boat and I prepare to row to the shore. Most of the portholes show round circles of light but one has a pair of bum knockers jammed up against it. I imagine that Boris must be enjoying his Saturday constitutional.

In the end it is eight o’clock in the morning by the time I get round to Sid’s place in trendy Vauxhall. The blooming current carried me all the way round to Plumstead Marshes before I was able to get ashore.

I am not in a good mood and it is with no little force that I bang on the heavy brass doorknocker. Frankly, I am surprised that nobody has nicked it. When they moved in, Rosie said that the area was coming up but a glance around suggests that most of it is coming down – either falling or being pulled. Looks like Sid got lumbered again. It is no good being the only house in the street with a lilac front door if it has ‘Poufdah!’ written on it with an aerosol paint spray. The door opens and there is Rosie wearing a black robe with Chinese dragons all over it. She is carrying a glass of orange juice.

‘You’re not having another kid, are you?’ I say, clocking the mittful of vitamin C.

‘Of course I’m not! I’m having my breakfast. What are you doing round here?’

‘I’m looking for Sid,’ I say, pushing past the colour supplement life-style and entering the house. Rosie has changed a lot since she got into the boutiques and wine bars. You would never catch her drinking orange juice for breakfast in the old days. Then it was a cup of tea and a marmite sandwich.

‘You might wipe your feet,’ she says. ‘And why are you wearing that ridiculous suit?’

I don’t answer her because I have just clapped eyes on Sid. He is sitting at a scrubbed pine table and reading a glossy brochure entitled Jetsetter Holidays in Brazil.

A puzzled and unhappy expression settles over his face as he sees me. ‘What are you doing here?’ he says.

‘I just walked from the Copacabana Beach,’ I tell him. ‘You can forget that for a start. “Drift across the Atlantic and taxi down the coast of South America to Rio de Janeiro.” I should cocoa!’

‘Are you coming, too?’ says Rosie. ‘Sid never tells me anything.’

‘I was going on ahead,’ I say. ‘By sea. I don’t suppose Sid told you that?’

‘He said he had to meet someone,’ says Rosie. ‘What is all this?’

‘Where’s the bed?’ says Sid. ‘You haven’t damaged it, have you? I sunk a lot of investment in that.’

‘You sunk it to the bottom of the Thames,’ I say. ‘It didn’t stay afloat more than a couple of hundred yards. It’s a miracle that I’m alive!’

Sid claps his hands to his head. ‘Gordon Bennett! I might have guessed you’d make a mess of everything. What is it about you?’

‘What are you two talking about?’ says Rosie.

‘Sid wanted me to drift round the world on a floating bed,’ I tell her. ‘The trouble was that it didn’t float.’

‘You didn’t have to drift,’ says Sid. ‘You could have rowed a bit. Your attitude’s typical of so many young people today. You want everything on a plate. It’s getting so a kid expects a Duke of Edinburgh Award for pulling out a sheet of bog paper.’

‘Drifting round the world on a bed?’ echoes Rosie. ‘That’s dangerous.’

‘Oh, belt up!’ snaps Sid. ‘If you want to say anything you can blame your perishing brother for putting the mockers on our holiday.’

‘What do you mean?’ says Rosie.

‘I can’t charge it to expenses if he hasn’t gone, can I? Just think about it. We might have had to wait there for months until he showed up.’

A glance at Rosie shows me that she is torn by what I have heard described as conflicting emotions. ‘We’re not going?’ she says. ‘But I’ve got all the clothes.’

Sid shrugs. ‘You’ll have to send them back to Carmen Miranda’s estate, won’t you?’

Rosie turns to me. ‘Are you sure you didn’t act a bit hastily, Timmy?’

‘I acted hastily, all right!’ I say. ‘If I hadn’t, it would be my corpse standing here! You don’t seem to understand the seriousness of what I’m telling you. I was nearly sent to my death.’

‘And I’d set my heart on it, too,’ says Rosie, sinking into a chair – for a moment, I think she is talking about me kicking the bucket.

‘You know who to blame,’ sulks Sid, wiping his cakehole