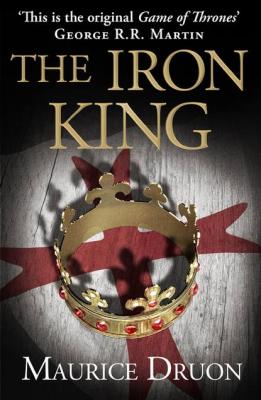

The Iron King. Морис Дрюон

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Iron King |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Морис Дрюон |

| Жанр | Историческая литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Историческая литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780007520930 |

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, Philip IV, a king of legendary personal beauty, reigned over France as absolute master. He had defeated the warrior pride of the great barons, the rebellious Flemings, the English in Aquitaine, and even the Papacy which he had proceeded to install at Avignon. Parliaments obeyed his orders and councils were in his pay.

He had three adult sons to ensure his line. His daughter was married to King Edward II of England. He numbered six other kings among his vassals, and the web of his alliances extended as far as Russia.

He left no source of wealth untapped. He had in turn taxed the riches of the Church, despoiled the Jews, and made extortionate demands from the community of Lombard bankers. To meet the needs of the Treasury he debased the coinage. From day to day the gold piece weighed less and was worth more. Taxes were crushing: the police multiplied. Economic crises led to ruin and famine which, in turn, caused uprisings which were bloodily put down. Rioting ended upon the forks of the gibbet. Everyone must accept the royal authority and obey it or be broken by it.

This cruel and dispassionate prince was concerned with the ideal of the nation. Under his reign France was great and the French wretched.

One power alone had dared stand up to him: the Sovereign Order of the Knights Templar. This huge organisation, at once military, religious and commercial, had acquired its fame and its wealth from the Crusades.

Philip the Fair was concerned at the Templars’ independence, while their immense wealth excited his greed. He brought against them the greatest prosecution in recorded history, since there were nearly fifteen thousand accused. It lasted seven years, and during its course every possible infamy was committed.

This story begins at the end of the seventh year.

A HUGE LOG, LYING UPON a bed of red-hot embers, flamed in the fireplace. The green, leaded panes of the windows permitted the pale light of a March day to filter into the room.

Sitting upon a high oaken chair, its back surmounted by the three lions of England, her chin cupped in her hand, her feet resting upon a red cushion, Queen Isabella, wife of Edward II, gazed vaguely, unseeingly, at the glow in the hearth.

She was twenty-two years old, her complexion clear, pretty and without blemish. She wore her golden hair coiled in two long tresses upon each side of her face like the handles of an amphora.

She was listening to one of her French Ladies reading a poem of Duke William of Aquitaine.

D’amour ne dois-je plus dire de bien

Car je n’en ai ni peu ni rien,

Car je n’en ai qui me convient …

The sing-song voice of the reader was lost in this room which was too large for women to be able to live in happily.

Bientôt m’en irai en exil,

En grande peur, en grand péril …

The loveless Queen sighed.

‘How beautiful those words are,’ she said. ‘One might think that they had been written for me. Ah! the time has gone when great lords were as practised in poetry as in war. When did you say he lived? Two hundred years ago! One could swear that it had been written yesterday.’

And she repeated to herself:

D’amour ne dois-je plus dire de bien

Car je n’en ai ni peu ni rien …

For a moment she was lost in thought.

‘Shall I go on, Madam?’ asked the reader, her finger poised on the illuminated page.

‘No, my dear,’ replied the Queen. ‘My heart has wept enough for today.’

She sat up straight in her chair, and in an altered voice said, ‘My cousin, Robert of Artois, has announced his coming. See that he is shewn in to me as soon as he arrives.’

‘Is he coming from France? Then you’ll be happy to see him, Madam.’

‘I hope to be … if the news he brings is good.’

The door opened and another French lady entered, breathless, her skirts raised the better to run. She had been born Jeanne de Joinville and was the wife of Sir Roger Mortimer.

‘Madam, Madam,’ she cried, ‘he has talked.’

Really?’ the Queen replied. ‘And what did he say?’

‘He banged the table, Madam, and said: “Want!”’

A look of pride crossed Isabella’s beautiful face.

‘Bring him to me,’ she said.

Lady Mortimer ran out and came back an instant later carrying a plump, round, rosy infant of fifteen months whom she deposited at the Queen’s feet. He was clothed in a red robe embroidered with gold, which weighed more than he did.

‘Well, Messire my son, so you have said: “Want”,’ said Isabella, leaning down to stroke his cheek. ‘I’m pleased that it should have been the first word you uttered: it’s the speech of a king.’

The infant smiled at her, nodding his head.

‘And why did he say it?’ the Queen went on.

‘Because I refused him a piece of the cake we were eating,’ Lady Mortimer replied.

Isabella gave a brief smile, quickly gone.

‘Since he has begun to talk,’ she said, ‘I insist that he be not encouraged to lisp nonsense, as children so often are. I’m not concerned that he should be able to say “Papa” and “Mamma”. I should prefer him to know the words “King” and “Queen”.’

There was great natural authority in her voice.

‘You know, my dear,’ she said, ‘the reasons that induced me to select you as my son’s governess. You are the great-niece of the great Joinville who went to the crusades with my great-grandfather, Monsieur Saint Louis. You will know how to teach the child that he belongs to France as much as to England.’1 fn1

Lady Mortimer bowed. At this moment the first French lady returned, announcing Monseigneur Count Robert of Artois.

The Queen sat up very straight in her chair, crossing her white hands upon her breast in the attitude of an idol. Though her perpetual concern was to appear royal, it did not age her.

A sixteen-stone step shook the floor-boards.

The man who entered was six feet tall, had thighs like the trunks of oak-trees, and hands like maces. His red boots of Cordoba leather were ill-brushed, still stained with mud;