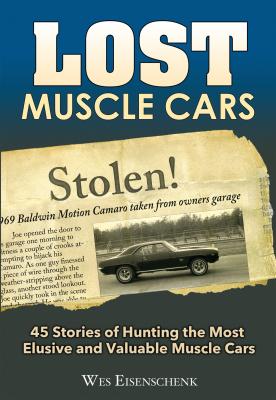

Lost Muscle Cars. Wes Eisenschenk

Читать онлайн.| Название | Lost Muscle Cars |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Wes Eisenschenk |

| Жанр | Автомобили и ПДД |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Автомобили и ПДД |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781613253120 |

The menacing stance of the Ford Super Cobra was enough to strike fear into anyone who happened upon it at a stoplight. Unfortunately, this was the last rendition of this body style. (Photo Courtesy Chicago Auto Show)

There were simply too many cars for the manufacturers to create themselves in the constantly changing muscle car wars. Outsourcing became a viable and successful tool in getting new cars to the market quickly.

Dodge used Creative Industries of Detroit and other sources to create Dream Cars like the Dodge Charger I and Dodge Charger II. Dodge also harnessed Creative’s designers to develop cars for racing programs as done with the Dodge Daytona and its in-house nemesis used Creative to build the Superbird.

Ford was doing the same at Kar Kraft, creating the Boss 429 and Torino Talladega, required for homologation in NASCAR as well, and the Boss 302 cars for Trans-Am racing. Styline Customs typically handled preparation and customization for show cars for companies such as Promotions Inc., but by 1969 they were waist deep in helping manufacturers create the Hurst Olds and the SC/Rambler, which needed to be produced for F Stock classification in the NHRA.

As much fun as it was creating cars for racing, manufacturers still had to focus on the general buying public, and they did so through auto shows.

Two of the biggest were the Chicago Auto Show and the Detroit Auto Show. At those venues, designers debuted their concepts and gauged public opinion and reaction. Other cars already slated for production were formally rolled out and introduced to the public for the first time.

The Mustang I made its debut at the U.S. Grand Prix race in 1962 held at Watkins Glen in upstate New York, but garnered much of its unfavorable public opinions from touring the auto shows. That sent Ford back to the drawing board, resulting in the design of the Mustang II. That car was received favorably by the public and became the blueprint for the development of the production models.

Unfortunately the survival rate for these promotional, concept, and prototype cars was fairly low. Some of them were cut up and parts were used for future endeavors while others were outright destroyed. With every production model, though, other cars were always created to re-start the design process.

Finding one of these cars and then working on verification of its authenticity can be daunting. Many of the designers who created these cars are no longer with us, which means that other types of historical documentation are needed. Hunting these cars is also difficult because some were never intended for public usage, and that means VINs and serial numbers were never part of the car.

Don’t be discouraged, though. With hard work and some sleuthing you may open a barn door and be staring at one of these lost muscle cars.

1969 Plymouth Superbird Prototype

By Wes Eisenschenk

Of all things to transpire after the 1968 Grand National (NASCAR) season, the defection of Richard Petty from Plymouth to Ford is perhaps one of the most overlooked separations in the history of motorsports. After nearly a decade of dominance, Petty, who had led the charge for Plymouth since switching from Oldsmobile during the 1959 season, was headed to the Blue Oval, and Plymouth had to go back to the drawing board.

In hindsight, 1968 wasn’t that terrible of a year for King Richard and his Plymouth Road Runners. In fact, Richard closed the year with 16 wins (two in his 1967 Plymouth) and finished strong with 5 wins in his last 10 races. Throw out his DNF at Charlotte (third-to-last race) and his average finishing position over those last 9 contests was 1.88.

Creative Industries of Detroit grafted a new nose onto a 1969 Plymouth Road Runner to construct the Superbird and began the process of luring Richard Petty back to Plymouth. (Photo Courtesy Richard Padovini and Winged Warriors Car Club)

He started the 1969 campaign in his 1968 Road Runner and ended up 1st at Macon and 2nd at Montgomery, finishing behind Bobby Allison, also driving a Plymouth. So why would Richard want to leave the auto manufacturer with whom he had so much success and who had seemingly been offering him competitive equipment?

The Dodge Influence

The answer was happening over at Dodge. Before the 1968 campaign, Dodge had rolled out an all-new Charger. Aesthetically, the car looked unbeatable. Competitively, it was a turd. It was so bad aerodynamically that in mid-1968 Chrysler began to rework the body at Creative Industries of Detroit in order to make the car more competitive for 1969. By adding a flush nose (donated from the Coronet) and removing the sail panels from the roofline, the Chargers became more cooperative at the high speeds on the superspeedways.

Dodge would have to build 500 production copies to make the car eligible for competition in NASCAR for the 1969 season. Rumors persist that when NASCAR officials visited Creative to count how many cars were constructed, employees simply drove around the building and through the entrance again so they were counted twice. The final tally was 392 Charger 500s built with NASCAR apparently none the wiser.

Obviously, the willingness of Dodge to help make the Chargers faster while Plymouth sat on its hands didn’t sit well with the Pettys. In truth, they weren’t getting the factory support that they felt they needed, whereas it appeared the Dodge drivers were. For 1969, Plymouth had indicated to Petty that he would be campaigning the reworked Road Runner that he had driven in 1968. This proved to be the proverbial nail in the coffin for Richard and his days at Chrysler.

On November 25, 1968, Richard announced that he would be headed to Ford for the 1969 Grand National season. For 1969 Ford Motor Company planned to debut the new drop-nosed Talladegas and Cyclone Spoiler IIs.

Charger Daytona Debut

With an ever-increasing transition from dirt ovals to paved super-speedways in NASCAR’s premier series, “aero” was the new term that everyone in the garage had to adhere to. Dodge began making the transition with the Charger 500 in 1968 but took things to a whole new level in 1969 because it just wasn’t satisfied with its race cars.

In early 1969, Dodge began work on the Charger 500’s successor, the Dodge Charger Daytona. The car was to debut in 1970, but plans changed when the Ford Talladega and Mercury Cyclone Spoiler II debuted at the Atlanta 500. This forced Chrysler to contract Creative Industries again to quickly begin production of the 503 copies for street use and NASCAR homologation.

In September at Talladega, the Charger Daytona debuted with its extended beak and grafted wing and with replacement driver Richard Brickhouse. Why Richard Brickhouse? Because 16 regulars, led by Richard Petty (head of the Professional Drivers Association), boycotted the race because of safety concerns.

With Brickhouse behind the wheel, the aero-sensitive machine ran laps consistently in the 197-mph range. The Daytona went on to win the race and ultimately ushered in Chrysler’s dominance, placing Chrysler on the throne for the next season and a half.

The prototype wing is applied to the rear quarter panels of the 1969 Road Runner at Creative Industries of Detroit. Similar to the 1969 Dodge Charger 500, a smaller rear window is also affixed to this Bird. (Photo Courtesy Richard Padovini and Winged Warriors Car Club)

Road Runner