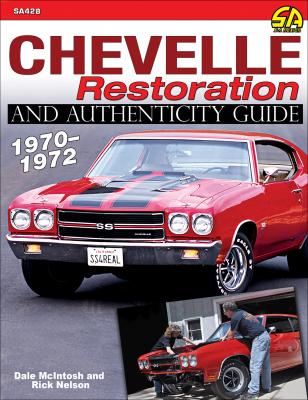

Chevelle Restoration and Authenticity Guide 1970-1972. Dale McIntosh

Читать онлайн.| Название | Chevelle Restoration and Authenticity Guide 1970-1972 |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Dale McIntosh |

| Жанр | Сделай Сам |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Сделай Сам |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781613255438 |

Jacks

At least one good floor jack and at least two but preferably four or more jack stands are needed to raise the car off the ground and support the chassis. A set of car dollies can be of great assistance if you plan on moving your rolling chassis around your garage or shop as well.

Bench Grinder

A bench grinder with both grinding and polishing heads is handy for touch-up finishing and final polishing of trim pieces. Adhesives for gaskets, weatherstripping, and special lubricants for brakes, windows tracks, etc. will also be needed.

Naturally, if you do not have or cannot borrow or rent these items, you will need to find a reputable body shop that is willing to take on the project and do the work. It is often difficult to find a local body shop to do a good restoration or even a passable one. The bulk of their business is insurance collision repair, and your project can sit for months with nothing being done and parts getting lost. Get a solid estimate up front of not only the work to be done and a price but the time frame for its completion. Most body shops will not make near as much money on your restoration as they do on collision work, so your car will always be the second priority in their shop, sometimes making the project last years.

Taking on Someone Else’s Project

Probably 60 to 70 percent of all projects get stalled at some point, and owners decide to move on. Extreme caution should be taken if considering another owner’s project. There are many questions to consider including: How much work has been done, and is it quality work? How much of the original driveline is left, and is it all there? Were removed parts tagged or bagged? Few things are as daunting as buying a roller with the engine and transmission out of the car; no trim or windows on the body; 15 milk crates of parts; and a few coffee cans of nuts, bolts, small trim pieces, etc. and none of it marked.

A project that has been assembled is much easier to work with. You will know exactly what has and has not been done and if all small pieces are there. A car that you purchased in primer and were told is “ready for paint” is usually not, and you have no way of knowing if the prep work was done correctly. If they did not acid wash the metal and remove all traces of oil or other contaminants from the body prior to priming, the paint will never stay on the car.

If you started the project yourself and decide it is more than what you bargained for or decide you want a concours restoration rather than a simple rebuild to drive, ensure you have all of your pieces and parts sorted in such a matter that the shop doing the rest of the work has everything you removed and tagged. Decide up front if you want the shop to call you and see if you can locate any parts needed or if you will opt to let the shop track down the missing parts. Missing parts can often hold up one area of the restoration, but work can still possibly continue in other areas. One important fact to keep in mind is a restoration shop will always charge you more for a project you started and didn’t complete than one that was brought to them from the beginning. That is even assuming you can find a shop willing to take on your already-started project.

Where to Start

We are going to begin with the assumption you are doing a concours-quality body-off-frame restoration. If your plan is something less, you can adjust your plan of attack accordingly.

Once you begin your project, get organized. Tag and/or bag every piece you remove along with a note of when in the process it was removed, so you can reinstall the pieces in correct order. After you reinstalled the dash assembly is not the time to remember you need to replace/repair the heater controls or the radio. Get a quality digital camera and document disassembly details with photos. Download them to your computer after each work session and note what you did and any difficulties encountered in the day’s work. In six months or a year, when you are putting it back together, you will forget something or misremember how it came apart. I also make separate files for the photos to make them easier to find when needed, such as body, chassis, drivetrain, interior, etc.

Lastly, I cannot emphasize enough to save all of your old parts until the restoration is complete. Many times, I refer back to the original part when I receive a replacement or donor-car part. This will ensure that what goes back on the car will be similar to what originally came off. You may also be able to use parts of the old part if needed.

Even if you plan on farming out the entire process of restoring your Chevelle, you should be aware of the time, effort, materials, etc. that your selected shop must invest in the restoration. While the factory could build a complete car in four or five days, it took hundreds of employees at numerous subassembly stations to put the car together. Quite a number of those major parts, such as driveline components, came pretty much assembled by scores of other employees at other plants.

The assembly plants did not have to worry about patching rusted body panels, stripping old paint, tearing out old interior and wiring, or waiting for a third party to complete the assembly of a major component. A concours restoration can take months, even years, to complete from chasing down those hard-to-find correctly dated parts that were changed and/or lost long ago to the quality of a small team of experts to assemble the car and, last but not least, to your finances.

CHAPTER 3

BODY DISASSEMBLY

Overcome the urge to dig right in and start unbolting pieces; get organized up front. Have a general plan of attack for the day. If today’s task is to disassemble the front sheet metal, have a place in mind to store the hood, fenders, bumper, radiator support, etc. beforehand. These large items can be difficult to store due to their size, and keeping them out of the way once they have been removed can be a challenge. Protect them from warpage; do not lay fenders on their sides, as they tend to flatten out over time. I buy the cheap $25 body-panel stands and set them on there. Take care that your hood and other body panels are not sitting on a wet or damp garage floor; this will only add to your rust issues. Take care of the hood corners.

Large plastic dairy crates are great for larger heavy items but tend to gather dust when stored for a time. Heavy-duty boxes will help with dust issues, but you cannot see what is inside the box. Be sure to label boxes clearly. I find that those large plastic totes are the best and are not very expensive. I then tag them with pieces of tape and separate them by category: body, interior, chassis, engine, etc. This makes it much easier when it comes time to reassemble the car, as you grab only the tote and its parts for the area you are currently working on.

The interior needs to be completely gutted along with all wiring removed and any mechanical attachments, such as steering linkage, transmission linkage, etc., removed, as you see here. Two heavy-duty bumper jacks are used here to lift the body from the frame, but any safe method you have available to you will work.

Clear plastic bags can be used for the smaller items such as nuts, bolts, alignment shims, etc. Be sure to note which side (driver’s side versus passenger’s side) with items such as fender alignment shims. Assuming the body panels were hanging nicely on the car when you disassembled it, I like making a shim map showing the location of the shims and what overall thickness was present in that area. This will give you a starting point come assembly time.

With camera, bags, and a marker in hand, it is time to get started. Unless you have a dozen friends and a camera crew filming everything, do not expect to have your car stripped in an afternoon like you will often see on television. Take your time during disassembly as you photograph the steps and mark and bag trim pieces, screws, bolts and nuts, etc.

Removal Methods

There are two ways to attack a restoration depending on your skills, space, access to specialty