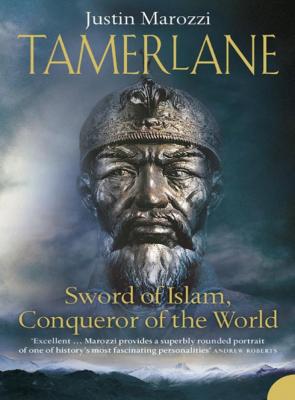

Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World. Justin Marozzi

Читать онлайн.| Название | Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Justin Marozzi |

| Жанр | Историческая литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Историческая литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780007369737 |

Temur was as avid a collector of wives as he was of treasures and trophies from his many campaigns. Although little is known about how many he had, and when he married them, from time to time they surface in the chronicles and then just as abruptly sink back into the depths of obscurity. We know that Saray Mulk-khanum was his chief wife, the Great Queen, a position she owed to her distinguished blood. Others followed. In 1375 he married Dilshad-agha, daughter of the Moghul amir Qamar ad-din, only to see her die prematurely eight years later. In 1378 he married the twelve-year-old Tuman-agha, daughter of a Chaghatay noble. Temur’s voracious appetite for wives and concubines did not lessen noticeably during his lifetime. In 1397, towards the end of his life, he married Tukal-khanum, daughter of the Moghul khan Khizr Khoja, who became the Lesser Queen. By this time, according to the hostile Arabshah, the ageing emperor ‘was wont to deflower virgins’. In terms of numbers of wives, Clavijo’s account is probably the most accurate. He counted eight in 1404, including Jawhar-agha, the youthful Queen of Hearts whom Temur had just married well into his seventieth year. An unknown number of others had predeceased him.

In the wake of Husayn’s defeat and execution, and in deference to the traditions of Genghis, by which only a man of royal blood could aspire to supreme command, Temur installed a puppet Chaghatay khan, Suyurghatmish, as nominal ruler. This was no more than a formality. All knew that power lay with Temur alone. ‘Under his sway were ruler and subject alike,’ Arabshah recorded, ‘and the Khan was in his bondage, like a centipede in mud, and he was like the Khalifs at this time in the regard of the Sultans.’

The realities of the power-sharing arrangement were underlined in a dramatic ceremony of enthronement. With the blessing of the qurultay of Balkh, Temur crowned himself imperial ruler of Chaghatay on 9 April 1370.* Majestic in his new crown of gold, surrounded by royal princes, his lords and amirs, together with the puppet khan, the new monarch sat solemnly as one by one his subjects humbly advanced, then threw themselves on the ground in front of him before rising to sprinkle precious jewels over his head, according to tradition. Thus began the litany of names he enjoyed until his death. At the age of thirty-four he was the Lord of the Fortunate Conjunction, Emperor of the Age, Conqueror of the World.

His greatness, said Yazdi, was written in the stars:

When God designs a thing, he disposes the causes, that whatever he hath resolved on may come to pass: thus he destined the empire of Asia to Temur and his posterity because he foresaw the mildness of his government, which would be the means of making his people happy … And as sovereignty, according to Mahomet, is the shadow of God, who is one, it cannot be divided, no more than there could have been two moons in the same heaven; so, to fulfil this truth, God destroys those who oppose him whom providence would fix upon the throne.

Had they been consulted, the countless millions who lost their lives over the course of the next four decades – buried alive, cemented into walls, massacred on the battlefield, sliced in two at the waist, trampled to death by horses, beheaded, hanged – would surely have differed on the subject of the emperor’s mildness. But they were beneath notice. No one, be he innocent civilian or the most fearsome adversary, was allowed to stand in the way of his destiny. The world would tremble soon enough. Temur’s rampage was only just beginning.

* A reference to Book 48 of the Koran, Al Fath (Victory): ‘We have given you a glorious victory, so that God may forgive you your past and future sins, and perfect His goodness to you; that He may guide you to a straight path and bestow on you His mighty help … God has promised you rich booty, and has given you this with all promptness. He has stayed your enemies’ hands, so that He may make your victory a sign to true believers and guide you along a straight path.’

* Founded in the eleventh century as the Knights of the Hospital of St John at Jerusalem, the military religious order in Smyrna was, by 1402, the last Christian stronghold in Asia Minor.

† Academics tend to dispute Temur’s actual birthday. Beatrice Forbes Manz, for example, author of a scholarly study of Temur, says this date was ‘clearly invented. He was probably at least five years older than the date suggests.’

* The Tatars were originally a powerful horde which held sway in north-east Mongolia as early as the fifth century. As with many of the other ethnic groups drawn from the melting-pot of Central Asia, a region which for thousands of years has been a crossroads for great movements of populations, the term is neither exact nor exclusive. The word itself may have originated from the name of an early chieftain, Tatur. In the thirteenth century, Genghis Khan’s westward rampages with his Mongols brought about a cross-fertilisation of cultures and peoples throughout the continent. Despite the fact that he had already virtually eliminated the Tatars as a tribe, these Turkicised Mongols became known as Tatars. Europeans, however, used the term indiscriminately for all nomadic peoples and, because they regarded these rough barbarians with fear and loathing, spelt it Tartar, from Tartarus, the darkest hell of Greek mythology. Today, the words Mongol and Tatar are often used interchangeably.

† ‘To speak of him as Tamerlane is indeed a matter of insult, being a name inimical to him,’ noted Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, the Spanish envoy sent to Temur’s court by Henry III of Castile in 1402. Such diplomatic niceties are still scrupulously observed among Uzbeks, as the author discovered 598 years later during an interview with Tashkent’s ambassador to the Court of St James’s. ‘We are very proud of Amir Temur. We do not call him Tamerlane,’ he told me with only the lightest and most diplomatic of reproaches.

* The chapter headings of Arabshah’s Life of Temur the Great Amir make this animosity abundantly clear: ‘This Bastard Begins to Lay Waste Azerbaijan and the Kingdoms of Irak’; ‘How that Proud Tyrant was Broken & Borne to the House of Destruction, where he had his Constant Seat in the Lowest Pit of Hell’. Elsewhere, Temur is described variously as ‘Satan’, ‘demon’, ‘viper’, ‘villain’, ‘despot’, ‘deceiver’ and ‘wicked fool’. Any praise for Temur from this quarter is therefore not to be taken lightly.

† Ibn Battutah earned the soubriquet ‘Traveller of Islam’ after a twenty-nine-year, seventy-five-thousand-mile odyssey around the world. He journeyed indefatigably by camel, mule and horse, on junks, dhows and rafts, from the Volga to Tanzania, from China to Morocco. Variously a judge, ambassador and hermit, he was also pre-eminently a travel writer, the stories of his epic wanderings recounted in the monumental The Precious Gift of Lookers into the Marvels of Cities and Wonders of Travel.

* The title of Khan was the most popular designation for a sovereign in medieval Asia. Initially it referred to kings and princes, but it was debased over the centuries to include local rulers and even chiefs.

* This figure, like many from the medieval chronicles, should be treated with a degree of caution. Scholars consider the population estimates and reports of the numbers killed in battles to be routinely inflated in these sources.

* The most controversial of sources relating to Temur’s life are the supposedly autobiographical Mulfuzat (Memoirs) and Tuzukat (Institutes). These date back to their alleged discovery in the early seventeenth century by a scholar called Abu Talib al Husayni, who presented