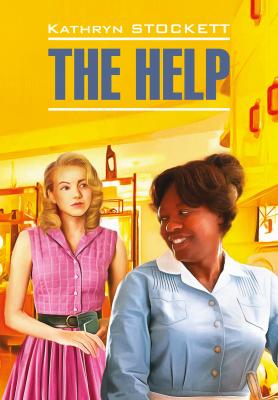

The Help / Прислуга. Книга для чтения на английском языке. Кэтрин Стокетт

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Help / Прислуга. Книга для чтения на английском языке |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Кэтрин Стокетт |

| Жанр | Современная зарубежная литература |

| Серия | Modern Prose |

| Издательство | Современная зарубежная литература |

| Год выпуска | 2017 |

| isbn | 978-5-9925-1208-3 |

And it’s not just the bed. Miss Celia won’t leave the house except to get her hair frosted and her ends trimmed. So far, that’s only happened once in the three weeks I’ve been working. Thirty-six years old and I can still hear my mama telling me, It ain’t nobody’s business. But I want to know what that lady’s so scared of outside this place.

Every payday, I give Miss Celia the count. “Ninety-nine more days till you tell Mister Johnny bout me.”

“Golly, the time’s going by quick,” she’ll say with kind of a sick look.

“Cat got on the porch this morning, bout give me a cadillac arrest[35] thinking it was Mister Johnny.”

Like me, Miss Celia gets a little more nervous the closer we get to the deadline. I don’t know what that man will do when she tells him. Maybe he’ll tell her to fire me.

“I hope that’s enough time, Minny. Do you think I’m getting any better at cooking?” she says, and I look at her. She’s got a pretty smile, white straight teeth, but she is the worst cook I have ever seen.

So I back up and teach her the simplest things because I want her to learn and learn it fast. See, I need her to explain to her husband why a hundred-and-sixty-five-pound Negro woman has keys to his house. I need him to know why I have his sterling silver and Miss Celia’s zillion-karat ruby earrings in my hand every day. I need him to know this before he walks in one fine day and calls the police. Or saves a dime and takes care of business himself.

“Get the ham hock out, make sure you got enough water in there, that’s right. Now turn up the flame. See that little bubble there, that means the water’s happy.”

Miss Celia stares down into the pot like she’s looking for her future. “Are you happy, Minny?”

“Why you ask me funny questions like that?”

“But are you?”

“Course I’s happy. You happy too. Big house, big yard, husband looking after you.” I frown at Miss Celia and I make sure she can see it. Because ain’t that white people for you, wondering if they are happy enough.

And when Miss Celia burns the beans, I try and use some of that self-control my mama swore I was born without. “Alright,” I say through my teeth, “we’ll do another batch fore Mister Johnny get home.”

Any other woman I’ve worked for, I would’ve loved to have had just one hour of bossing them around, see how they like it. But Miss Celia, the way she stares at me with those big eyes like I’m the best thing since hairspray in the can, I almost rather she’d order me around like she’s supposed to. I start to wonder if her laying down all the time has anything to do with her not telling Mister Johnny about me. I guess she can see the suspicious in my eye too, because one day, out of the blue[36] she says:

“I get these nightmares a lot, that I have to go back to Sugar Ditch and live! That’s why I lay down so much.” Then she nods real fast, like she’s been rehearsing this. “Cause I don’t sleep real well at night.”

I give her a stupid smile, like I really believe this, and go back to wiping the mirrors.

“Don’t do it too good. Leave some smudges.”

It’s always something, mirrors, floors, a dirty glass in the sink or the trash can full. “We’ve got to make it believable,” she’ll say and I find myself reaching for that dirty glass a hundred times to wash it. I like things clean, put away.

“I wish I could tend to that azalea bush out there,” Miss Celia says one day. She’s taken to laying on the couch while my stories are on, interrupting the whole time. I’ve been tuned in to The Guiding Light for twenty-six years, since I was ten years old and listening to it on Mama’s radio.

A Dreft commercial comes on and Miss Celia stares out the back window at the colored man raking up the leaves. She’s got so many azalea bushes, her yard’s going to look like Gone With the Wind[37] come spring. I don’t like azaleas and I sure didn’t like that movie, the way they made slavery look like a big happy tea party. If I’d played Mammy[38], I’d of told Scarlett to stick those green draperies up her white little pooper. Make her own damn man-catching dress.

“And I know I could make that rose bush bloom if I pruned it back,” Miss Celia says. “But the first thing I’d do is cut down that mimosa tree.”

“What’s wrong with that tree?” I press the corner of my iron into Mister Johnny’s collar-point. I don’t even have a shrub, much less a tree, in my entire yard.

“I don’t like those hairy flowers.” She gazes off like she’s gone soft in the head. “They look like little baby hairs.”

I get the creepers with her talking that way. “You know about flowers?”

She sighs. “I used to love to tend to my flowers back in Sugar Ditch. I learned to grow things hoping I could pretty up all that ugliness.”

“Go head outside then,” I say, trying not to sound too excited. “Take some exercise. Get some fresh air.” Get out a here.

“No,” Miss Celia sighs. “I shouldn’t be running around out there. I need to be still.”

It’s really starting to irritate me how she never leaves the house, how she smiles like the maid walking in every morning is the best part of her day. It’s like an itch. Every day I reach for it and can’t quite scratch it. Every day, it itches a little worse. Every day she’s there.

“Maybe you ought to go make some friends,” I say. “Lot a ladies your age in town.”

She frowns up at me. “I’ve been trying. I can’t tell you the umpteen times I’ve called those ladies to see if I can help with the Children’s Benefit or do something from home. But they won’t call me back. None of them.”

I don’t say anything to this because ain’t that a surprise. With her bosoms hanging out and her hair colored Gold Nugget.

“Go shopping then. Go get you some new clothes. Go do whatever white women do when the maid’s home.”

“No, I think I’ll go rest awhile,” she says and two minutes later I hear her creeping around upstairs in the empty bedrooms.

The mimosa branch knocks against the window and I jump, burn my thumb. I squeeze my eyes shut to slow my heart. Ninety-four more days of this mess and I don’t know how I can take a minute more.

“Mama, fix me something to eat. I’m hungry.” That’s what my youngest girl, Kindra, who’s five, said to me last night. With a hand on her hip and her foot stuck out.

I have five kids and I take pride that I taught them yes ma’am and please before they could even say cookie.

All except one.

“You ain’t having nothing till supper,” I told her.

“Why you so mean to me? I hate you,” she yelled and ran out the door.

I set my eyes on the ceiling because that’s a shock I will never get used to, even with four before her. The day your child says she hates you, and every child will go through the phase, it kicks like a foot in the stomach.

But Kindra, Lord. It’s not just a phase I’m seeing. That

bout give me a cadillac arrest – (

out of the blue – (

Gone With the Wind – «Унесенные ветром», фильм, снятый по роману Маргарет Митчелл о Гражданской войне

Mammy – Мамушка, чернокожая служанка Скарлетт О’Хара из «Унесенных ветром»