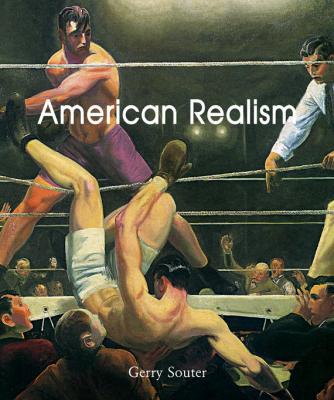

American Realism. Gerry Souter

Читать онлайн.| Название | American Realism |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Gerry Souter |

| Жанр | Иностранные языки |

| Серия | Temporis |

| Издательство | Иностранные языки |

| Год выпуска | 2016 |

| isbn | 978-1-78042-992-2, 978-1-78310-767-4 |

Another motivation to shift over to paint and brush was the advance of technology in the engraving trade. Electroplating, invented in the 1840s, allowed an industrial approach to what had been a hand-executed artisan craft. The assembly line was replacing the artist’s bench. In 1874 Harnett painted his first oil painting – which he was able to sell – of a still-life with a paint tube and grapes.

The painting is hardly a world beater, but it tapped into a market that had greater promise than the diminishing demand for his engraving skills. The painting also marked an advance beyond the studies offered at the National Academy. It was the practice at that time to offer painting to only the most advanced students. Part-timers like Harnett had to find painting lessons in the atelier of a full time professional artist. He wrote of his frustrations with this arrangement:

“I ventured to take a course of lessons from Thomas Jensen, who was at that time a famous painter of portraits. I paid him in advance and intended to finish the course, but I couldn’t do it. He didn’t exactly say I would never learn to paint, but he didn’t offer me any encouragement. After I had studied with him for ten days, I asked him how a certain fault of mine could be corrected. I shall never forget his answer.

“‘Young man,’ he said, ‘the whole secret of painting is putting the right colour in the right place.’

“The next day I went back to my old way of study.”[24]

William Michael Harnett, Trophy of the Hunt, 1885.

Oil on canvas, 107.8 × 55.4 cm.

The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Harnett packed up and moved back to Philadelphia in 1876, rejoining his mother and sisters and enrolling once again in the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts. By this time, one would imagine he could write his own ticket at the Academy. He was a professional artist, exhibiting and selling his paintings. However, he exhibited and sold mostly in public places: building lobbies, saloons, restaurants and billiard rooms. The critics wrote him off as having little talent other than patience. Trompe-l’œil art had the same reputation as humorous paintings with animals such as Dogs Playing Poker – non-aesthetic placebos for the masses.

Although he enrolled in life drawing classes at the Academy, Harnett continued to pursue still-lifes as his bread and butter work, seeking out varieties of textures and surfaces that appeared to be totally random. Of his working methods, very little documentation was left behind. Only an observation by his friend Edward Taylor Snow has survived stating Harnett would “make a finished lead pencil drawing with minute details prior to executing a painting”.[25]

Until infrared reflectography began revealing carbon under painting details, little was known about the sequence of events with that drawing. Today, we can see the pencil lines directly on the canvas, and other mysteries have come to light. For one thing, the pencil drawing was not the necessarily the final disposition. In Still-Life with Violin and Music, for example, the violin’s scroll has been significantly thinned. In other works, whole background elements have been painted over to simplify the compositions. He sometimes altered the subjects, removed handles from jars, tassels from pipes and shifted bits of paper or creased their corners as he painted.

While he used the pencil guides in his earlier paintings, the more he worked, the more often he applied his placement of objects directly on the background colour. Harnett used a pointed tool or the end of his brush to scribe a line in directly into the background and then painted into it. As he worked, he fattened jugs and shortened canes to maintain correct spatial relationships and scale to honour the composition. He continued to use some form of background drawing for object placement and painted his subject matter elements in front of each other, as they existed in reality.

William Michael Harnett, Cigar Box, Pitcher, and “The New York Herald”, 1880.

Oil on canvas, 20.1 × 19.7 cm.

Courtesy of Berry-Hill Galleries, New York, New York.

In his paintings of the late 1870s produced in Philadelphia, The Banker’s Table, painted in 1877, shifts Harnett’s subject matter from trivial collections of fruit, dishes, flowers, vegetables and other frivolous objects to hard currency and realities of commerce. His time in New York might have introduced him to these symbols of finance as the new icons of American progress. The country had shifted into the Industrial Revolution of factories and finance, mass production and rapid communications following the Civil War. Ledger books, an antique quill pen and a wad of bank notes held down with a coin wrapper of silver dollars sit next to what appears to be a gold Double Eagle. However, the activities, both social and industrial, of the Gilded Age were built on a foundation of unease, a corrupted morality that Harnett seems to grasp. Ashes spill from overturned pipes, crumbs litter table tops, age and patina darken well-handled instruments, brass is left unpolished and reveals the subtle dents of hard use. Nothing seems new.

He became involved with gathering both the symbols of national commerce and personal items as well: letter racks, business cards, addressed envelopes, newspapers, elements of after-work relaxation showing pipes, tobacco cans, musical instruments and recreation. His Cigar Box, Pitcher and “New York Herald” reproduces a variety of textures in a strictly male context that seem to have followed an event. There is a story-telling quality to the collection of objects. The pitcher anchors the right side while the wood cigar box of cheap Colorado Gold cigars is the Cigar Box, Pitcher and "The New York Herald" centrepiece. It is the details that tell the story. A Dutch porcelain pipe sans shank has a cigar butt stuffed into its bowl – a method pipe smokers use to enjoy a hot short cigar or cigarillo – with the burnt matches dropped casually on the table cloth. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the upside-down New York Herald banner of the half-folded newspaper beneath the jug, and a mug of tea, claret or other drink sits behind the cigars. Two biscuits with crumbs complete the scene as if waiting for the smoker to return and finish his snack and clean up the mess.

In 1880 Harnett sailed for Europe, the birthplace of trompe-l’œil painting. The style dated back to 400 B. C. and can be found in the murals recovered from the ruins of volcano-devastated Pompeii. A famous story from the historian Vasari tells of two competing trompe-l’œil artists who arranged a contest to see who could paint the most realistic scene. One artist painted a bowl of fruit with such faithful detail that birds fluttered down to peck at the grapes. Certain he had won, he turned to his rival and crowed loudly, “Draw back the curtains and reveal your painting!” The rival then knew he had won because the curtains were his painting. Another tale of the time told of Rembrandt’s pupils in his studio taking time to paint coins on the floor and then laugh uproariously when the master bent down to pick them up.

Murals painted in the Baroque and Renaissance by Andrea Mantegna, Paolo Uccello and Paolo Veronese utilised trompe-l’œil techniques in churches and palaces to open what architect Leone Alberti referred to as “windows into space”.

Harnett had earned enough with his painting sales in Philadelphia to support himself in Europe where he studied and exhibited his new works in London, and the Paris Salon, finally spending four years in Germany. His arrival in Munich at that time was fortunate as the influence of seventeenth-century Dutch art with its still-life tradition was just making itself felt in Munich in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. His still life paintings had received their typical good reactions among the people of London and Paris, but as usual the critics ho-hummed his style as boring. Painting was undergoing a loosening of styles, a freer use of brushes and palette knives, an explosion of colour and lighter schemes as the Impressionists began to make their presence felt. But in Munich,

Alfred Frankenstein,

Stanley V. Henkels,