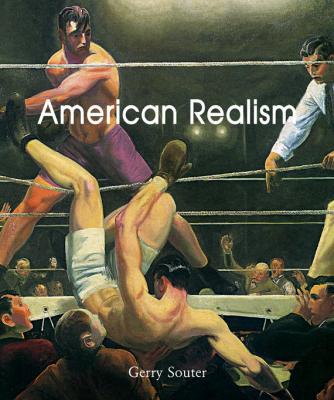

American Realism. Gerry Souter

Читать онлайн.| Название | American Realism |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Gerry Souter |

| Жанр | Иностранные языки |

| Серия | Temporis |

| Издательство | Иностранные языки |

| Год выпуска | 2016 |

| isbn | 978-1-78042-992-2, 978-1-78310-767-4 |

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut.

Winslow Homer was a meticulous planner when executing his paintings, but watercolours held another appeal to his creativity. He could work more quickly and increase his production, thereby adding to his income. He also keenly observed the work of other artists, especially after his trip to Paris and exposure to the upstart French Impressionists. His palette lightened considerably and he became one of America’s first ‘modernist’ painters.

Another curious fact has arisen lately concerning this 1870s-80s period of his genre painting. The watercolour Reading, done in 1874 of a fair-haired girl in a dress stretched out the full length of the picture reading a book is in fact a boy hired by Homer to play the part of a girl. This discovery led to similar instances where Winslow Homer substituted boy models for girls. Of course this returns to the matter of his sexual orientation, or did he just feel more comfortable negotiating rates with a boy than a girl?

Did his thwarted relationship with Helena de Kay drive a nail into his further dealings with women – except as observed for a sketch – as subjects? Is that the reason many of his later portraits of young women show pensive, unsure, sad faces? Most women are painted alone or with another woman – but almost never with a man. Does this alienation from women – according to Allston’s teachings – represent a ‘secondary’ subject showing through the ‘primary’ image?

Homer decided to leave for the British Isles in 1881. He visited the British Museum and studied the Elgin Marbles stolen from the Greek Parthenon. He pondered the romanticism of Pre-Raphaelite painters such as Edward Burne-Jones and from these studies changed his style to more painterly, dramatic images. He had accumulated all the tools he needed over the years and now shut off his previous society and locked himself into his work. He settled in the coastal fishing village of Cullercoats in Northumberland on the North Sea where the River Tyne empties its currents.

On these shores he documented the fishermen’s daily struggles with the sea and devoured the bleak vistas and salt-scoured rocky coves, the deep rolling combers of the pitiless North Sea. His study of Japanese prints in the 1860s now offered up unusual compositions that placed man at the mercy of the elements. He sought out the families of the fishermen and their hard life, waiting on the beach as their men searched for the great living shoals of fish.

What he found at the edge of the North Sea he brought home with him in 1882 when he moved to a house in Prout’s Neck, Maine, a tide-blasted promontory that thrusts out into the Atlantic. There, he continued to explore with his watercolours, sketchbooks and oils.

Homer’s admiration for the men who went to sea is obvious in his watercolours of their harrowing occupation and the skills needed to survive out on the Grand Banks.

When winter arrived, Homer departed to Florida, Cuba and the Bahamas to paint the native fishermen in their small boats. During these trips, he often was accompanied by his father. Besides the sea, the outdoors attracted his attention. He loved roughing it in the woods and found pleasure in the company of trappers and other woodsmen who spent their lives in direct contact with nature.

Often, he made summer trips up to Essex County, New York and what appeared to be a boarding house in a clearing deep in the woods. This was the North Woods Club of which he became a member in the 1880s. Many members built cottages on the property and the hearty life coupled with rough and sturdy men appealed to Homer. He spent much time tramping about the Adirondacks, fishing, hunting, and relaxing in what became the club house. He painted the men, the forest and the women who ran most of the local boarding houses and camps. He also travelled up into Canada for similar subject matter.

The wilderness seemed to have a calming effect on Homer. His cronies in New York would not have recognised their hail-fellow-well-met carouser with a short fuse. Among the woodsmen and Adirondack residents he was quiet, shy, and capable in woodcraft. He painted images of them and listened to their stories.

He shared their adventures and eventually moved among them as an equal rather than a tourist. The bitter recluse, often reported by people who visited his Prout’s Neck home and studio unannounced or seeking interview, vanished in the great forest.[9]

Finally, at the age of seventy-four he visited the North Woods Club in June 1910. Knowing he was mortally ill, he wanted to experience the serenity and power of the unspoiled wilderness one last time. He was attended by his friend and live-in servant, an African-American named Lewis Wright who had lived with Homer since 1895. They stayed for ten days and then returned to his old rambling house at Prout’s Neck in Scarborough, Maine. His visits to the Adirondack woods had resulted in some well-designed magazine illustrations, fourteen oil paintings and roughly one hundred watercolours. He worked with his watercolours right up to the end because he wanted no unfinished work left behind to be ‘completed’ by some hack with his, Homer’s, name on it. On 29 September, 1910, he died with one painting still on his easel. Shooting the Rapids, Saguenay River remains unfinished. He was laid to rest at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He had achieved fame and success in his lifetime by his own efforts. He was largely self-taught and spoke a language with his oils and watercolours that still resonates with modern viewers. He was a complex and very private man who drained life to the bottom of the cup – and up-ended the cup when he was finished.

Winslow Homer, Coast in Winter, 1892.

Oil on canvas, 72.4 × 122.6 cm.

Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Thomas Eakins (1844–1916)

Thomas Eakins, The Champion Single Sculls (Max Schmitt in a Single Scull), 1871.

Oil on canvas, 81.9 × 117.5 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, the Alfred N. Punnett Endowment Fund and George D. Pratt gift.

Thomas Eakins was a brilliant artist, but a failed human being. He brought the realism skills of the European salon painter to the American scene, but left behind the scattered detritus of a rather cruel and sordid lifestyle. He had a gift for technique and capturing emotion on canvas, but some of the emotions he captured were the result of his reclusive and demanding personality. On the one hand, his contemporary cronies and colleagues thought him a fine fellow, if a bit overbearing and driven. The personal side of his relationships with women and relatives and many of the people he painted was littered with sorrow, suicides and madness. Despite the dualism of his nature, he emerges as one of the most influential and important American Realist artists of his era.

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (pronounced “Ache-ins”) was born on 25 July 1844 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which eventually became his sole base of operations. He was a painter, photographer and sculptor. His parents were his Dutch-English mother, Caroline Cowperthwait and Benjamin Eakins of Scots-Irish ancestry. His father was the son of a weaver and took up calligraphy and the art of fine copperplate writing. He moved from Valley Forge to Philadelphia to pursue that trade. Thomas was their first child and by the age of twelve he admired the exactitude and precision required to produce calligraphic script and printing. This early exposure to careful planning and diagramming images stayed with him and became an important part of his creative method.

His love of the physical sports he later painted, rowing, ice skating, swimming, wrestling, sailing, and gymnastics also began in his youth. His academic life started in Philadelphia’s Central High School, the finest school in the area for applied sciences and both practical and fine art. Eakins maintained his consistency by settling into mechanical drawing. In his late teens, he shifted to the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts to study drawing and anatomy and then expanded his anatomical studies at the Jefferson Medical College from 1864–65. Though he started out following his father into calligraphy and becoming a ‘writing master’, his studies in anatomy had motivated him towards medicine and surgery. The quality of his drawing, however, earned him a trip to Paris to join the classes

David Tatham,