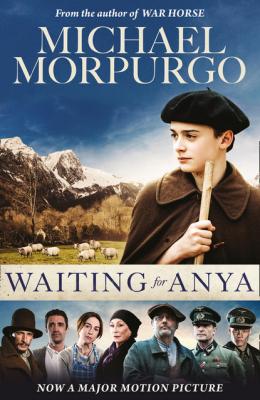

Waiting for Anya. Michael Morpurgo

Читать онлайн.| Название | Waiting for Anya |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Michael Morpurgo |

| Жанр | Учебная литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Учебная литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781780311418 |

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

JO SHOULD HAVE KNOWN BETTER. AFTER ALL PAPA had told him often enough: ‘Whittle a stick Jo, pick berries, eat, look for your eagle if you must,’ he’d said, ‘but do something. You sit doing nothing on a hillside in the morning sun with the tinkle of sheep bells all about you and you’re bound to drop off. You’ve got to keep your eyes busy, Jo. If your eyes are busy then they won’t let your brain go to sleep. And whatever you do, Jo, never lie down. Sit down but don’t lie down.’ Jo knew all that, but he’d been up since half past five that morning and milked a hundred sheep. He was tired, and anyway the sheep seemed settled enough grazing the pasture below him. Rouf lay beside him, his head on his paws, watching the sheep. Only his eyes moved.

Jo lay back on the rock and considered the lark rising above him and wondered why larks seem to perform when the sun shines. He could hear the church bells of Lescun in the distance but only faintly. Lescun, his village, his valley, where the people lived for their sheep and their cows. And they lived with them too. Half of each house was given over to the animals, a dairy on the ground floor, a hay loft above; and in front of every house was a walled yard that served as a permanent sheep fold.

For Jo the village was his whole world. He’d only been out of it a few times in all his twelve years, and one of those was to the railway station just two years before to see his father off to the war. They’d all gone, all the men who weren’t too young and who weren’t too old. It wouldn’t take long to hammer the Boche and they’d be back home again. But when the news had come it had all been bad, so bad you couldn’t believe it. There were rumours first of retreat and then of defeat, of French armies disintegrating, of English armies driven into the sea. Jo did not believe any of it at first, nor did anyone; but then one morning outside the Mairie he saw Grandpère crying openly in the street and he had to believe it. Then they heard that Jo’s father was a prisoner-of-war in Germany and so were all the others who had gone from the village; except Jean Marty, cousin Jean, who would never be coming back. Jo lay there and tried to picture Jean’s face; he could not. He could remember his dry cough though and the way he would spring down a mountain like a deer. Only Hubert could run faster than Jean. Hubert Sarthol was the giant of the village. He had the mind of a child and could only speak a few recognisable words. The rest of his talk was a miscellany of grunting and groaning and squeaking but somehow he managed to make himself more or less understood. Jo remembered how Hubert had cried when they told him he couldn’t join the army like the others. The bells of Lescun and the bells of the sheep blended in soporific harmony to lull him away into his dreams.

Rouf was the kind of dog that didn’t need to bark too often. He was a massive white mountain dog, old and stiff in his legs but still top dog in the village and he knew it. He was barking now though, a gruff roar of a bark that woke Jo instantly. He sat up. The sheep were gone. Rouf roared again from somewhere behind him, from in among the trees. The sheep bells were loud with alarm, their cries shrill and strident. Jo was on his feet and whistling for Rouf to bring them back. They scattered out of the wood and came running and leaping down towards him. Jo thought it was a lone sheep at first that had got itself caught up on the edge of the wood, but then it barked as it backed away and became Rouf – Rouf rampant, hackles up, snarling; and there was blood on his side. Jo ran towards him calling him back and it was then that he saw the bear and stopped dead. As the bear came out into the sunlight she stood up, her nose lifted in the air. Rouf stayed his ground, his body shaking with fury as he barked.

The nearest Jo had ever been to a bear before was to the bearskin that hung on the wall in the café. Stood up as she was she was as tall as a full-grown man, her coat a creamy brown, her snout black. Jo could not find his voice to shout with, he could not find his legs to run with. He stood mesmerised, quite unable to take his eyes off the bear. A terrified ewe blundered into him and knocked him over. Then he was on his feet, and without even a look over his shoulder he was running down towards the village. He careered down the slopes, his arms flailing to keep his balance. Several times he tumbled and rolled and picked himself up again, but as he gathered speed his legs would run away with him once more. All it needed was a rock or a tussock of grass to send him sprawling once again. Bruised and bloodied he reached the track to the village and ran, legs pumping, head back, and shouting whenever he could find the breath to do it.

By the time he reached the village – and never had it taken so long – he hadn’t the breath to say more than one word, but one word was all he needed. ‘Bear!’ he cried and pointed back to the mountains, but he had to repeat it several times before they seemed to understand or perhaps before they would believe him. Then his mother had him by the shoulders and was trying to make herself heard through the hubbub of the crowd about them.

‘Are you all right, Jo? Are you hurt?’ she said.

‘Rouf, Maman,’ he gasped. ‘There’s blood all over him.’

‘The sheep,’ Grandpère shouted. ‘What about the sheep?’

Jo shook his head. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘I don’t know.’

Monsieur Sarthol, Hubert’s father and mayor of the village as long as Jo had been alive, was trying to organise loudly; but no one was paying him much attention. They had gone for their guns and for their dogs. Within minutes they were all gathered in the Square, some on horseback but most on foot. Those children that could be caught were shut indoors in the safekeeping of grandmothers, mothers or aunts; but many escaped their clutches and dived unseen into the narrow streets to join up with the hunting party as it left the village. A bear hunt was once in a lifetime and not to be missed. This was the stuff of legends and here was one in the making. Jo pleaded with Grandpère to be allowed to go but Grandpère could do nothing for him, Maman would have none of it. He was bleeding profusely from his nose and his knee, so despite all his objections he was bustled away into the house to have his wounds cleaned and bandaged. Christine, his small sister, gazed up at him with big eyes as Maman wiped away the blood.

‘Where’s the bear Jo?’ Christine asked. ‘Where’s the bear?’

Maman kept saying he was as pale as a ghost and should go and lie down. He appealed one last time to Grandpère, but Grandpère ruffled his hair proudly, took his hunting rifle from the corner of the room and went out with everyone else to hunt the bear.

‘Was it big, Jo?’ said Christine tugging at his arm. She was full of questions. You could never ignore Christine or her questions – she wouldn’t let you. ‘Was it as big as Hubert?’ And she held up her hands as high as she could.

‘Bigger,’ said Jo.

Bandaged like a wounded soldier he was taken up to his bedroom and tucked under the blankets. He stayed in bed only until Maman left the