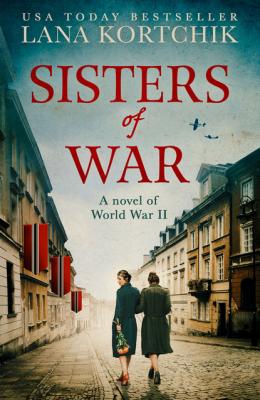

Sisters of War. Lana Kortchik

Читать онлайн.| Название | Sisters of War |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Lana Kortchik |

| Жанр | Исторические любовные романы |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Исторические любовные романы |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780008314835 |

*

When they thought it was safe, the girls and Alexei ventured cautiously from behind the fence. The streets that were busy only moments earlier were now deserted. The silence was tense, expectant. And only occasionally, as they walked down Tarasovskaya Street, did Natasha hear loud voices coming from Lva Tolstogo Boulevard. Natasha felt a chill run through her body because they were not Russian voices but German. The unfamiliar sounds spoken so assertively on the streets of Kiev seemed to defy the natural order of things.

At the entrance to their building, Alexei tried to say goodbye but Lisa grabbed his hand. ‘Where do you think you’re going?’

‘Home,’ he said, making a half-hearted attempt to break free.

‘It’s too far. And too dangerous.’ Alexei lived three short tram stops away. Since the tram was no longer running, it was a twenty-minute walk.

‘I’d rather face the Nazis than your father.’

But Lisa was adamant. ‘Don’t go back to an empty house. Come home with us.’

Together the three of them climbed eight flights of stairs to the sisters’ apartment. Natasha dawdled on the stairs, taking forever to find her key. She realised she didn’t want to be the one to give the terrifying news to her family.

‘Girls, is that you? We’re in the kitchen.’ Mother’s voice sounded unusually shrill. Natasha took her time removing her shoes, hesitating before walking down the long corridor. Would Mother cry when she heard? And what would Father say when he realised that, despite his specific instructions, they were out when the Germans entered Kiev? A captain in the militia, he ruled the household just like he did his subordinates at work. He was strict, brusque, devoid of emotion, and everyone who came into contact with him was in awe of him. Everyone, that was, except her mother, who with a couple of well-chosen words could defuse even the biggest storm.

It was dim in the kitchen. The radio was playing Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, Natasha’s favourite. The familiar chords never failed to make her smile, but today the music was accompanied by German shouts coming from the window, as platoon after platoon of soldiers in grey marched through the city. Lisa hid behind Natasha, all her earlier bravado forgotten. But Father barely glanced in their direction. His face ashen, he was bent over the table, every now and then barking short sentences into the telephone receiver that he cradled with his shoulder. ‘Heavy losses? Southwestern Front destroyed?’

Natasha shivered.

‘We saw—’ Lisa started saying, her eyes wide.

‘Have something to eat,’ said Mother. She looked as if she had just stepped out of bed. Her hands, her long musician’s fingers were fidgeting, picking up cups, wiping the table that was already clean. ‘Alexei, please, come in. Would you like some soup?’

‘We’re not hungry, Mama,’ said Lisa. ‘We saw German soldiers outside.’

Father rose to his feet and, still holding the telephone, started pacing from one wall to the other. It took him three strides to cover the distance between the two walls. His steps resonated ominously in the quietened kitchen. Finally, he reached for a cigarette, even though he already had one in his mouth, and put the phone down.

‘Bad news?’ asked Mother.

Father didn’t seem to hear. ‘They’re finally here. There are thousands of them in the city.’

Lisa nodded. Mother gasped. Alexei collapsed into a chair and said, ‘Thousands?’

‘I hope Stanislav is okay, wherever he is,’ exclaimed Mother. Natasha’s older brother Stanislav had been drafted into the Red Army in June. The family hadn’t heard from him since.

Natasha whispered, ‘What’s going to happen to us? Papa, what are we going to do?’

Father startled as if her words woke him from an unpleasant dream. He narrowed his eyes on Natasha and said, ‘It won’t be for long. We just need to sit tight and wait for the Red Army to come back.’ As usual, his stern voice allowed for no arguments. And only his hands were shaking.

Natasha didn’t know what to think. She didn’t know what to expect. German occupation, what did it mean? She turned to her mother, who was fidgeting in her chair and not looking at Natasha. She turned to her father, who was smoking grimly and not looking at Natasha. She turned to Lisa and Alexei, who were staring out the window in stunned disbelief. Natasha suspected that her sister, who thought she knew everything but knew nothing, and her mother, too afraid to think straight, and even her father, who ruled their family with an iron fist, didn’t have any answers.

The only thing Natasha Smirnova knew for a fact on 19th September 1941, when Hitler entered Kiev, was that life as she knew it was over.

*

All was quiet in the city at night, and Natasha, who had become accustomed to the distant sound of war, couldn’t sleep. For three months she had dreamt of being able to go to bed and not hear the buzz of the cannonade, and not hear the explosions and the mortars that were getting closer and closer, as if seeking her out. But now, as she lay in bed with her eyes wide open, she didn’t rejoice at the peace in Kiev. She didn’t rejoice because of what this peace signified. The silence meant there was no Red Army, no planes with red stars on their wings and no chance of a Soviet victory. Instead, the enemy troops were finally here. Like an oppressive shadow, Natasha could sense their presence, even here in the safety of her bed. How would they treat the local population? What if right now, while Natasha was asleep, someone marched through the door and – and what? She didn’t know what exactly she was afraid of, but she was afraid all the same. It was an abstract fear of things to come, a fear that pulled on her chest and made her heart ache. From this moment on, Kiev was a city oppressed, occupied and enslaved. And no one she knew and loved was safe.

The clock in the corridor chimed midnight. Natasha, who was sleeping on a small folding bed in her grandparents’ room, could hear Lisa tossing and turning in her bed in the room next door. Natasha got up and crossed the small space that separated the two rooms, peering in. Her eyes were used to the dark and she could make out Lisa’s shape as she curled up in bed. Instantly she felt less lonely, and her heart felt lighter. The weight she was carrying wasn’t hers alone. She had her sister to share it with.

‘Lisa, are you awake?’ she whispered, and her voice came out eerie and unfamiliar. She perched on the edge of her sister’s bed.

‘I am now.’ Lisa didn’t sound scared or uncertain. Just annoyed at being disturbed. ‘What is it, Natasha? It’s late.’

‘What do you think is going to happen to us?’

‘I guess the same thing that’s been happening to us since June.’

‘But now they’re here.’

‘There’s nothing we can do about it. We’ll just have to learn to live with it.’

‘How do we do that, Lisa? How do we learn to live with it?’

‘You heard Papa. It won’t be for long,’ said Lisa. ‘Before we know it, our army will come back and boot the Nazis out.’

‘Yes, but what if they don’t? What if it takes months or even years?’ Natasha shuddered. Years under German occupation? She couldn’t imagine living like this for another day. Although she didn’t know what to expect, her whole being rejected the idea.

‘Let’s take it one day at a time. Don’t think about it now. Think about it tomorrow. Try to get some sleep. Goodnight, Natasha.’

‘Goodnight, Scarlett O’Hara.’

It had always been like this.