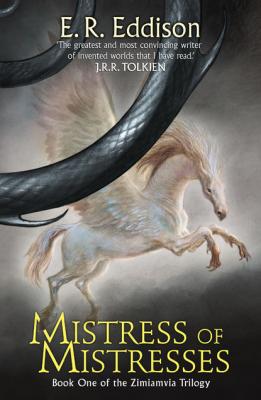

Mistress of Mistresses. E. Eddison R.

Читать онлайн.| Название | Mistress of Mistresses |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | E. Eddison R. |

| Жанр | Сказки |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Сказки |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780007578146 |

Melates looked warily round, ‘I taught you that, my lord: ’tis a fine toy, but in sober sadness I am not capable of it. Nor you neither, I think.’

Zapheles said, ‘’Twill yet bear thinking on. You have here your natural sovereign lord (o’ the wrong side of the blanket may be; no matter, that’s nor here nor there); you yield him service and upholding: well. You look for quiet, therefore, and to be lord of your own, being suffered to enjoy these borders whereof you have right and particular dominion. Good: then behold your payment. He is practised upon most devilishly; even ladies will shortly scoff and prattle of it, that he is grown as tractable to’t as stock-fish. You’ll say that’s his concernment; in the midst of idleness and deliciousness, fanned with the soft gales of his own flatterers’ lips, he sitteth content. Good. But must we take cold too, ’cause he hath given his cloak away? Must I smile and sit mum (and here’s a right instance hot upon me like new cakes) when that Beroald taketh up a man I ne’er saw nor heard on, took in his lordship’s own private walks with a great poisoned dagger in his breeches; a pretty thing it was, and meant beyond question for my lord Chancellor; they hanged him where he stood, on a mulberry-tree; and, ’cause the vile murderer said with a lie that this was by County Zapheles his setting on, I am at short warning cited before the justiciars to answer this; and the Duke, when I appeal to him under ancient right of signiory to have the proceedings quashed under plea of ne obstes and carried before him in person (which should but have upheld his authority, too much abridged and bridled by these hireling office-nobility), counsels me kindly waive the point of jurisdiction. And why? but that he will not be teased with these matters; which yet ensueth neither the realm’s good nor his.’

‘To amend which,’ said Barrian, ‘you and Melates would in plain treason give over all to the Vicar?’

‘Would if we were wise,’ replied Melates; ‘but for fond loyalty sake, will not. May be, too, he is loyal, and would not have us.’

Zapheles laughed.

Barrian said: ‘Your own men would not follow you in such a bad enterprise.’

‘’Tis very true,’ said Zapheles. ‘And indeed, were’t otherwise, they should deserve to be hanged.’

‘And you and I too,’ said Melates.

‘And you and I too. Yet in the Parry you may behold a man that knoweth at least the right trick to govern: do’t through lords of land, like as we be, bounded to’s allegiance, not parchment lords of’s own making.’

‘Were the Duke but stiffened to’t!’ said Melates. ‘You are his near friend, Barrian: speak to him privately.’

‘Ay,’ said Zapheles. ‘Nay, I mock not: choose but the happy occasion. Say to him, “You are Meszria: our centre whereto all lines come, all things look. Who depriveth this merchandise of reverence, defaceth all lustre of it. To it, then: out with Beroald, out with Roder and Jeronimy: throw the fowl to the Devil that hatched it.”’

‘Great and thumping words,’ said Barrian. ‘But ’tis mere truth a hath not the main strength to do it and he would. But hist, here’s the Chancellor.’

The company by the door made way right and left with many courtesies and loutings, which the Lord Beroald acknowledged with a cold and stately smile. His gait was direct and soldierly, he carried his head like a mettled horse, and on his lean countenance, flat in the cheekbones, wide between the eyes, clean cut about the jaw, close shaven save for the bristly brown mustachios, sat that look which, as lichens grow on rock-faces, comes but with years of constant lordship over men and their long customed obedience. ‘See how the spongy sycophants do hang on his steps,’ said Zapheles. ‘You’d swear they feared he should have ’em called in question for simple being here in Acrozayana. And the Duke will not put down his foot, it shall soon come to this indeed; a main crime to do him this empty courtesy, attend the weekly presences, without leave asked of this great devil and his fellows. See how he and Jeronimy do draw to a point of secret mischief as the lode-stone draweth iron.’

For the Chancellor, ending now his progress up the hall, was stood with the Lord Jeronimy on the great carpet before the throne. To them, as presenting in their high commission, along with Earl Roder, the King’s very person and authority in Meszria, was accorded these many years the freedom of the carpet; and that was accorded to none other in all the land who was not of the Duke’s own household or of the ducal line of Memison.

‘I am glad to see you here, my lord Admiral,’ said Beroald; ‘and indeed it is a joy I scarcely looked for: thrice in three weeks, and you were not formerly given to great observance of this ceremony.’

The Admiral looked at him with his dog-like eyes, smiled slowly, and said, ‘I am here to keep the peace.’

‘And I on the same errand,’ said Beroald: ‘and to please my lady sister. I would have you look a little more starved, as I myself do study to do. It is nought useful to remind him how we made new wood when the young King pruned away his appanage.’

There’s that needs no reminding on,’ said Jeronimy.

‘Will your lordship walk a little?’ said Beroald, taking him by the arm, and, as they paced slowly to and fro, cheek by cheek for convenience of private conference: ‘I still do hear it opinioned that it was not without some note or touch of malice these things were brought about; and you are named in that particular, to have set the King’s mind against him.’

Jeronimy blew out his cheeks and shook his head. ‘May be I was to blame; but ’twas in the King’s clear interest. I’d do it, were’t to do again tomorrow.’

‘This country party love us the worse for it,’ said Beroald.

‘A good housewife,’ answered Jeronimy, ‘was ever held in bad report with moths and spiders.’

‘We can show our teeth, and use them, if it were come to that,’ said Beroald. ‘But that were questionable policy. Too many scales stand in too uncertain balance. Roder’s long tarrying in Rerek: I like it not, ha?’

‘As if the King should think he needed men there.’

‘You have no fresh despatches?’

‘Not since that I showed you, a-Thursday sennight.’

‘That was not so bad, methought. My lord Admiral, I have a question I would move to you. Are we strong enough, think you, to hold off the Vicar if need were?’

Jeronimy looked straight before him awhile; then, ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘with the Duke of our side.’

‘You have taken me?’ said Beroald. ‘Supposition is, things fall out worst imaginable: war with him in Rerek, and the King’s forces overthrown. You are confident then?’

‘With the Duke of our side, and with right of our side, I should hope to do it.’

‘I too,’ said the Chancellor, ‘am of your opinion.’

‘Well, what’s the matter?’ The Lord Jeronimy came to a stop in his slow deliberate pacing. A gentleman of his household waited below the carpet: he seemed short of breath, as one that hath run a course: with a low leg he made obeisance, drawing a packet from his doublet. Jeronimy came to him, took it, and looked carefully at the seal with the gold-mounted perspective-glass that hung by a fine chain about his neck. Men marked how his sallow face turned sallower. ‘Just,’ he said: ‘it hath all the points in it.’ He undid the seal and read the letter, then handed it to Beroald; then, scowling upon the messenger: ‘How hapt, ninny-hammer, that you delivered this no sooner?’

‘Lord,’ answered he, ‘his lordship, all muddied from hard riding, did write it in your own house; and upon his sudden injunction strung with