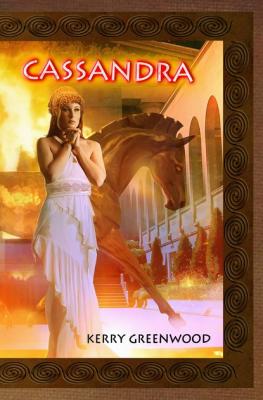

Cassandra. Kerry Greenwood

Читать онлайн.| Название | Cassandra |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Kerry Greenwood |

| Жанр | Историческая литература |

| Серия | The Delphic Women |

| Издательство | Историческая литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780987160423 |

Hector was lying on his cloak, the purple himation of the prince of Ilium. All the royal house were dressed in purple, derived from boiling murex shells. We were not allowed to go down by the dyers because of the dreadful smell, so it became a fascinating and forbidden place, and we went there when we could, although Nyssa always knew because of the stink and because our feet were dyed by contact with the running gutters. Then she scrubbed us with soapleaf and pumice stone and scolded all the while.

We never minded Nyssa scolding. We learned a lot of new words. The only way she could effectively punish us was to separate us - we were proof against spanking and words ran off us like water off a turtle's shell. But when separated we cried so lamentably, and above all so loudly, that she always relented after about an hour and put us back together again. Whereupon we would cease crying instantly and embrace and then think of something even more wicked to do. Poor Nyssa - we led her a trying life.

Eleni and I were lying either side of Hector, resting our chins on his chest. He was broad shouldered, our brother, and we liked the way the muscles moved under his skin when he breathed. He was as golden as a lion, with a mane of bright hair and a bristly golden beard as thick as twigs at the roots. His hands were big, with golden hair on the back, which I liked to tug at, and his arms were massive and bound with gold bracelets. He wore a pale green tunic of the cloth which came out of Egypt and was called linen. They make it out of reeds.

He had laid aside the pot of ink which he always wore on his neck, with the scribe's pen in it, and the scroll of Egyptian papyrus to make notes on. Our brother made notes about everything. He was the arranger of the city, the king our father's right hand. Hector knew, to a bale, how much wool we had sold to Phrygia; how much amber and tin bought from Caria; and how much pottery and how many necklaces from Achaea, down to the last and tiniest bead. He knew how many horses were in any of the king's herds, their breeding, their increase and their value as chariot horses or plough beasts. Hector had at his little finger's end more knowledge of the people of Troy, their trades, their occupations, and their private lives, than all of Priam's sons who sailed and traded across the Pillars of Heracles and up and down the shoreless sea.

They said in the city that he had numbered the winds and counted the tides, and they laughed at him, though carefully and out of earshot. They might curse his name and his family all the way back to Dardanus, as they searched a hold for a forgotten ingot or accounted for a lost sheep eaten by wolves the previous winter, but they trusted him, and he was very strong, a mighty warrior when there was cause. Was it not Hector Cuirass of Troy who had led a charge against the Mycenaean pirates who had landed and sacked a village, killing them to the last man?

Lying on Hector's chest was his cat, a creature called Státhi, or `ash' because of the colour of his fur. He was a gift from a grateful priestess in the Nile delta, from a place called Bubastis. We did not ask what she was grateful for and Hector never told us. Státhi was the first cat we had ever seen in the fur. He was about the same size as a small dog, though dogs were terrified of him, and he had thick, deep velvety fur, ash-coloured and barred with black like burned wood. His eyes were leaf green and cool. Hector had been given him as a small cub, and had carried him in his tunic against his heart for the length of the voyage, afraid that such a small creature might die of cold. Thereafter Státhi considered Hector the only human worth noticing - I think he thought our brother was a large furless cat - and was distant with all others, if not hostile. Once Eleni and I had pulled his tail and been swiftly punished for our impudence with a hand each sliced across with talons as sharp as a hawk's. We had not noticed that Státhi had claws - he kept them concealed in his paws - and we were much astonished and had howled. Hector had not been sympathetic.

`Státhi is a divine creature, the servant of a goddess,' he had reproved us. `You must expect to be hurt if you provoke him.'

Státhi had never seemed like a servant to us. He had a royal, arrogant leisure in all his movements. When the palace dogs attacked him in a body, barking at this strange new creature, he called upon his lady and she doubled his size, endowing him with eyes that glowed like embers and teeth of strongest ivory. She had also given him a scream which rose from a growl to a shriek, a voice that summoned all within hearing to the rescue.

Not that he needed rescue. The dogs, thoroughly unnerved, decided that there were other things that urgently needed their attention and thereafter left him severely alone. He still occasionally slapped an intrusive nose with his thorned paw, just to remind them that a goddess' friend was present, and they always retreated, howling. Státhi would sometimes allow a caress from someone other than Hector, and Eleni and I loved to stroke his velvety fur. But he would endure the caress rather than enjoy it, and when he was tired of the touch he would turn and bite, hard. The city called him `Hector's shadow' because, unless he had important business in the palace kitchens, he was always at the prince's heels, an aloof and mystical being, interested in everything, following his own purposes.

Hector had once found him in the goddess' shrine, seated with his tail wrapped around his paws, staring into the eyes of the sacred serpents, who also sat coiled and apart. Divine creatures recognise each other's divinity.

`Tell us a story,' we begged, keeping a wary eye on Státhi who might scratch if we disturbed him. Hector stared up at the starry sky. It was summer, and hot in the palace below, It was cooler on the roof, where there is always a breeze.

`I've been unloading ships all day,' he said sleepily. `What sort of story?'

`About us.'

`About Troy.'

Hector sighed - our chins rose and fell with his breath - and said, `Do you see those stars? The shape like a square, over there?'

`We see them,' said Eleni, speaking for both of us.

`Once in the Troad, before this city was built, there was a king who had a beautiful child.'

Státhi, liking the sound of Hector's voice, settled down into a crouch. We snuggled closer to our brother's sides and wrapped the folds of his cloak around us all.

`The child's name was Ganymede,' said Hector. Like his hair, his voice was golden, slightly husky and sweet on the ear. He continued, `The child was so beautiful that the god himself wanted him as a lover, so he sent an eagle down to the house of Tros and the eagle of the gods took the child up into the air, high as the sky, and brought him to the god. There he was much beloved, until the god's other lover, a daughter of the goddess, grew jealous. Then the father, to save the child, lifted him higher into the cosmos and placed him among the stars. They call him Aquarius, the water-bearer.'

`And is he happy?' I asked. `Wouldn't he rather be a prince of Troy like you? Didn't his mother and father cry for him?'

`They gave Tros and his wife two great horses - the mother and father of the horse herds of Troy.'

`But they were horses, not a son,' said Eleni, echoing thought.

`Gods will not be denied, twins,' said Hector gently. `When a god requires a life, then it cannot be denied. All people can do is make the best bargain they can.'

`Could an eagle come and carry us off?' Eleni asked anxiously. Everyone told us that we were beautiful, and we were twins, too - that might attract a god's notice. Hector laughed so much that he jolted us off his chest. He hugged us close and sat up, groaning, much to the displeasure of Státhi.

`An eagle could not possibly carry you off,' he said, rubbing at his chest where our chins had rested. `You are much too heavy for one poor eagle.'

We were comforted by this, and we all drifted off to sleep.

II

Diomenes

I was six when I died.

I heard Glaucus, master of Epidavros, talking to my father, their voices blurring in the gloom. My eyes were dimming. I could no longer feel my hands or feet. I was beyond the awful pain which had burned through my insides. I floated for a little, listening.

`The boy has eaten nightshade berries,' the master said evenly. `They are lethal. There is nothing we can do. The boy will die.'

`Is