Bride of the War. Doris Alma (Taylor)

Читать онлайн.| Название | Bride of the War |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Doris Alma (Taylor) |

| Жанр | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780963355843 |

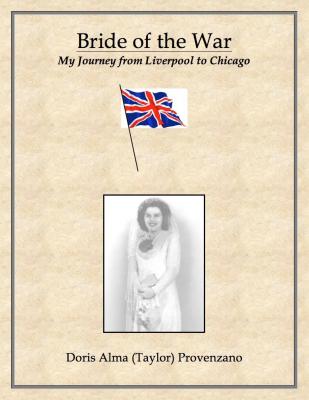

Bride of the War

My Journey from Liverpool to Chicago

(Title inspired by my granddaughter Lauren at age 15.)

By

Doris Alma (Taylor) Provenzano

Copyright © 2012

Publisher: ECS Executive Career Services & DeskTop Publishing, Inc.

Converted by http://www.eBookIt.com

Steven Provenzano, Editor

ISBN-13: 978-0-9633-5584-3

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quote short excerpts in a review.

CHAPTER ONE

[no image in epub file]

The city of Liverpool sits on the river Mersey in northern England and was once one of the busiest shipping ports in the world. Slaves were brought in from Africa and sold at the docks there over 200 years ago, and there are still chains attached to the walls; a sad reminder of man’s inhumanity to man. Many of the slaves were sent to America to pick cotton, which was then sent back to Liverpool for processing in the cotton mills. Ships returned to America, delivering guns and cannons. It’s home to many Irish immigrants from across the Irish Sea, just a three-hour ferryboat ride away. It was also a stopping off place for many immigrants from Europe on their way to America; they went there to find work in the many factories, iron foundries and the Lancashire cotton mills, hoping to make enough money to finish their journey. Many of them got no further, having families to support, that’s why Liverpool is a melting pot, the same as America; in fact, it was often called “Little America.”

Long before anyone ever heard of the Beatles and eleven years before World War II started, I was born in a Liverpool suburb called Fazakerley. Growing up with two brothers and a sister, we would play outside until it was dark, which was ten o’clock at night in the summer. We would play a game called rounders; it is much like American baseball but with four bases, then home. We used four trees in the street for bases.

Wintertime was just the opposite; it was dark at four o’clock, short days and long nights. We spent many nights around our small fire in the living room. My Dad would tell us stories about his seven years in India, how he rode a horse as a member of the Queen’s Cavalry, and how they all suffered from the heat. It would be as high as 120 degrees, and they were used to cool, mild, English weather. He was supposed to stay two years, but the army kept him there for seven. He joined the army when he was 17.

My dad had a very harsh childhood and a very strict Victorian upbringing with a hard mother. He had three brothers and a sister, who all left, or where told to leave, when they reached their teens. His brother Winston left at 14, ran away to Canada and worked as a lumber jack, he came home at age 28, knocked on the door, his mother opened it and then slammed it in his face. His brother Joe went off to London to seek his fortune, brother Harry got married and left, and his sister, my Auntie Lu, ran off to London and joined the chorus on stage.

He said when they were little, they all sat on a bench in the kitchen while their parents ate their meals. When they were through, they would get up, leave the table and the kids would sit down and eat what was left. He never went back after the war, he married my mum and I never saw his. He would meet his Dad at the Liverpool football ground, watch the game and say goodbye. My mum said his Dad was a good man, but completely under his wife’s thumb, probably a case of peace at any price.

My mum’s family where the exact opposite, she was one of ten children, five boys and five girls, a big loving family. My Grandma Christopher was left to raise them on her own, while my Grandpa was away fighting, in World War I, from 1914 to 1918. She was little, barely five feet tall, but she had a heart of gold. I was her first grandchild, and we were very close. I would visit her on a Saturday, and help out, or go to the store for her, along with her dog, a German Shepherd, named Dixie. As a rare treat, she would take me to the local cinema to see the latest Shirley Temple movie. We had some great days out on south road beach, a stretch of sand off the river Mersey, we would pack salmon sandwiches and hopefully eat them before someone would run past and kick sand into them. We took gallons of lemonade, and bought pots of tea from the vendors; if we had any money left we could buy an ice cream, a luxury at the time.

[no image in epub file]

We depended on the fireplace for everything, it had an oven connected to it, my mother cooked and baked in it. There were no dials or temperature gages, but everything came out perfect. We made our toast on it using a long fork. We boiled the kettle on it to make our tea, and heated the iron on it to iron our clothes. That was quite a project, first we would have to clean the soot off, then attach a metal shield to cover it, by then it was cooled down and we had to start all over again.

Our upstairs bedrooms were cold. All we had throughout the house was the fire in the living room, no central heating. My sister Margie and I would take the oven shelf out, wrap it in newspaper and put it in the bed to warm our feet. It was hard getting out of that bed in the morning, we went down the stairs real fast, to get in front of the fire, my dear little mum would have it going for us. She called that fire the heart of our home; I didn’t think so when I had to clean out the ashes.

The fire’s most useful function was to dry our clothes; the English weather is so wet and rainy. On wash day the clothes would go into a boiler with a gas jet under it. She would stir the clothes around with a wooden stick, lift them out with the stick, and drop them into cold water in the bathtub next to it. She’d rinse them out by hand, then put them through the mangle, between the rollers. All by hand, my mum would get everything washed, wrung through the mangle, hang them out on the line, then the rain would come down. Everything was brought back in the house and hung around the fire on a clothes rack called a maiden; never ending work for my mum.

I had chronic Bronchitis all of my life. My mum would put a kettle on the fire, sit me in front of it with a sheet over my head, and I would inhale the steam, there were no antibiotics in those days, we had to do the best we could.

When I was ten years old, my baby brother Billy was born. I was so excited when my mum brought him home, and since I was the oldest I could hold him on my lap. I tried to make him look at me but he just kept staring at the light in the ceiling. We found out weeks later that he was blind, and that flashes of light was all he could see. My mum offered to donate one of her eyes, but was told there was nothing to attach it to. He went on to have a full life and lost no time in learning to read and write Braille.

A big event every year was the running of the Grand National race on the course near our house; we would sneak in and sit on top of the railway embankment and watch the horses go over the jumps. It was a long and grueling race for them. One year we saw a horse fall, and the Bobby [policeman] hit it between the eyes with his club to put it out of its misery, it was very traumatic for us kids.

My mum had a great sense of humor; she could keep us going with her cheerful manner. When she made a bowl of Jell-O for us, a rare treat, she said “just put it at the foot of our bed, it will soon set”. We never had a refrigerator, our food was bought fresh daily; my mum would walk to the shops every day, and one bottle of milk was delivered every morning. I would sneak out early and eat the cream off the top of the bottle where it settled and then put the top back on.

We all walked everywhere; the only person I knew with a car was our family doctor. I did ride in it once, he came to the house when I had diphtheria, and he rolled me inside a big red blanket