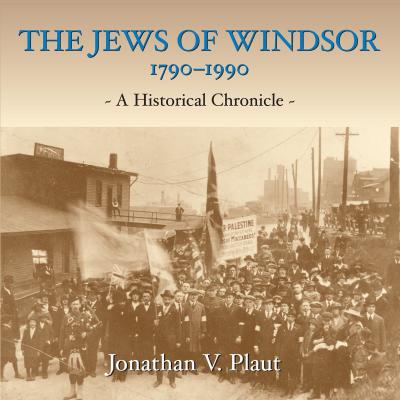

The Jews of Windsor, 1790-1990. Jonathan V. Plaut

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Jews of Windsor, 1790-1990 |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Jonathan V. Plaut |

| Жанр | Зарубежная эзотерическая и религиозная литература |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Зарубежная эзотерическая и религиозная литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781550029420 |

Cheifetz & Co

H. Meretsky

S. Abrahamson

S. D. Sumner

M. Meretsky & Son

H. H. Samuels

*Joel Gelber became president of the Border Cities Retail Merchants Association in 1923.133

Although most of these merchants had lived in the “Jewish Colony” at the turn of the century, by 1920, several had moved into other, predominantly Gentile neighbourhoods. Since many had purchased valuable properties or erected impressive buildings there, their assets now could be measured in ways other than the ever-increasing sizes of their stores.134 By 1912, Nathan Cherniak and Herman Benstein had each erected two-storey frame homes, costing $2,000 and $2,900, respectively.135 Although Simon Meretsky could not write his name and signed all documents with an “X,” he nevertheless had become most successful in real estate, owning land, buildings, and theatres — properties individually valued at between $20,000 and $25,000.136 Others involved in similar acquisitions, as well as in construction projects, were Aaron Meretsky, Joseph Kovinsky, S. K. Baum, Charles Rogin, Louis Kaplan, Samuel Schwartz, and Joseph Loikrec.137

In the socio-economic stratum, business and property ownership were only two facets of Jewish successes. Although none of the sons of the early pioneers had, as yet, entered the legal profession, by 1920, a few of them had become physicians. Max Bernstein’s son, Albert was the first Windsor Jew to attend the Detroit College of Medicine. Following his graduation in about 1906, he set up a medical practice in Detroit.138 Dr. S. Gelber, son of Joel, after graduating in 1909, moved to Denver, Colorado;139 Dr. David H. Weingarden, son of Isaac, joined the staff of Detroit’s Grace Hospital in 1914;140 Abraham Kovinsky, son of Joseph, after graduating in 1915, set up his medical practice in Detroit,141 while Dr. Isidore Cherniak’s career as a physician began in 1917.142

Louis Kaplan Feed Store and Coal Yard (n.d.).

The names of those Jews who reached financial and academic prominence have been preserved in the annals of the Windsor community. However, since we have no written records of the many who barely eked out a living, we know little about them and their stories are hardly ever told. Yet, we must not lose sight of the fact that, while labouring on hundreds of tasks, they too raised families to the best of their abilities. Their contributions, therefore, must be measured by their dedication, in general, to Judaism, and specifically to the growth and development of Windsor’s Jewish community.

Chapter 4

Widening the Horizon

Windsor in the Era of the Great War

The Border Cities entered the teens with great expectations. An announcement was made in 1913 that Ojibway had been selected as the site of the US Steel Corporation’s Canadian plant. The prospect of twinning autos with a similar steel industry made many in the area almost giddy. Through interests allied with the Canadian Bridge Company, the Essex Terminal Railway extended a line to the site and Ojibway was incorporated as a town, the next Border City. A real estate boom developed causing the price of the adjacent farmland to soar to $1,500 an acre. Ojibway lots were sold to purchasers all over the continent; speculation was rampant.

Skilled labourers, organized in artisan or craft unions, were merging into trades and labour councils and becoming a potential political power in the community. By 1918, they would produce a progressive platform, run a slate of candidates for City Council, and elect a third of the councillors. Industrial workers, perhaps basking in the promise of mass production and Henry Ford’s $4-a-day wages in Canada, would have to experience tougher times before taking similar action. Ford’s paternalism towards his workers was expressed through a Sociological Department whose investigators made regular home visits to ensure that they lived up to his conception of family values. His English Language School, supplied by the company and staffed by volunteers, provided many new immigrant workers with an opportunity to learn the national language and prepare for citizenship. The village, which had arisen around the Ford Works, achieved town status in 1915 and was seen as the coming community in the area.

Following the war, 1919 was the year of strikes in Canada — the Winnipeg General Strike being the most famous. In Windsor, the SWA (Sandwich, Windsor, and Amherstburg Railway) strike of that year was considered by the most conservative elements in the city as “Bolshevik inspired” and needing the full weight of heavily armed military forces to quell the impending threat to the established order. Gas and Water Socialism was at its height following the creation of Ontario Hydro in 1906 and in numerous instances of municipal ownership of energy sources, mass transportation, and other infrastructure and services. The citizens of the Border Cities voted for public ownership of the SWA, which was accomplished in 1920 under the prompting of Ontario Hydro’s “Power Knight,” Sir Adam Beck.

The Great War broke out in 1914 and Canada dutifully joined the British Imperial contingent. Windsor’s industries provided important war materials such as trucks and ambulances, shells, ammunition, and uniforms. The community came together in support of the war effort in a number of ways: Victory Loans, patriotic funds, and sewing and knitting woollens and warm clothing. Peace brought returning veterans to bask in the heartfelt gratitude of their communities through a series of civic receptions and church services. Canada’s new international status, marked by membership in the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization (ILO), had been earned by great sacrifices both at home and abroad.

Windsor’s Jews had not gone to war, but the community did their part in supporting the war effort. Of more importance, perhaps, were the consequences of peace. In 1917, the Balfour Declaration gave British support for a permanent home for refugee Jews in Palestine. Zionism had always been popular among a certain segment of the Jewish population and this issue brought deep feelings to the surface.1

The Beginning of Diversity

The initial struggles of any pioneering group intent on survival are usually dramatic. Windsor’s budding Jewish community was no exception. Its members, no longer able to insulate themselves entirely from their surroundings, had learned to interact with their non-Jewish neighbours. Yet, mindful of their solid commitment to family members and to others in their extended community, they methodically laid the building blocks for a cohesive society.

Shaarey Zedek, their first synagogue,2 had been the place where they had worshipped together, learned, debated, and often quarrelled. Although it had, initially, served as a unifying force, successive events proved that it was not an ivory tower in which everyone spoke with one voice. If conflicting opinions had brought about a parting of the ways — the emergence of Tifereth Israel as a separate religious entity3—that split, eventually, led to the development of numerous other Jewish organizations and facilities that allowed all those able to take advantage of them to freely express a variety of thoughts and viewpoints.

The Importance of Education

Since Jews have been reading and studying sacred texts for centuries, they always have been known as the “people of the book.” Regardless of how poor they were or how often the whims of rulers in the various European countries where they tried to settle forced them to move from place to place, Jewish parents always instilled in their children that knowledge was something they could take with them wherever they went. Education was a means for attaining security.

Although these children had attended parochial schools that taught Jewish subjects exclusively, when they came to North America they were compelled to enroll in secular institutions.4 In Windsor, seven public schools and one collegiate institute existed prior to 1901. School taxes were levied on all ratepayers, with the Protestants paying 60 percent and, in the absence of a Separate School Board before 1901, Catholics were assessed 25 percent,