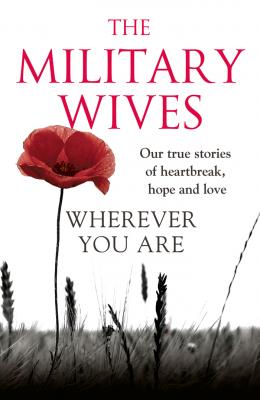

Wherever You Are: The Military Wives: Our true stories of heartbreak, hope and love. The Wives Military

Читать онлайн.| Название | Wherever You Are: The Military Wives: Our true stories of heartbreak, hope and love |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | The Wives Military |

| Жанр | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Биографии и Мемуары |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780007488971 |

SSAFA Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Families Association: a charity that helps serving and former members of the armed forces, their families or dependents

TRIM Trauma Risk Management: designed to identify and help forces personnel at risk after traumatic incidents, delivered by trained people already in the affected individual’s unit

UNDERSTANDING RANKS

ARMY AND ROYAL MARINES

Private

Lance Corporal

Corporal

Sergeant

Staff Sergeant

Colour Sergeant: the same rank as Staff Sergeant, used in the Royal Marines and some regiments

WO2: Warrant Officer class 2 (Sergeant Major)

WO1: Warrant Officer class 1 (Regimental Sergeant Major)

OFFICERS’ RANKS

2nd Lieutenant

Lieutenant

Captain (LE Captain is someone who has worked up through the ranks; LE stands for Late Entry)

Major

Lieutenant Colonel

Colonel

Brigadier

Major General

Lieutenant General

General

NAVY (NON-COMMISSIONED RANKS)

Rating

Leading Hand

Petty Officer

Chief Petty Officer

Warrant Officer

ROYAL AIR FORCE (NON-COMMISSIONED RANKS)

Leading Aircraftman

Senior Aircraftman

Corporal

Sergeant

Flight Sergeant

Warrant Officer

‘He tells me I’ve got to be strong for the children, and he’s right. But who’s going to be strong for me?’

We don’t just marry a man we love: we marry a way of life. Our lives are dominated by his career, in a way that rarely happens outside the military. We move home, on average every two years, as he is posted from camp to camp. Our children are uprooted; our own careers and ambitions go on hold. We live in houses we did not choose, we make friends who move on as soon as we have become close. It’s not an easy life, and that’s without the biggest challenge of all: our men leave home to go to the world’s most dangerous places, leaving us behind to nurse our loneliness and learn to be both mother and father to our children.

When they go, we struggle to put a brave face on it. We don’t want to distract him: we’ve heard the saying ‘If his head’s at home, he’ll struggle out there.’ So we accept, and are even glad, that as he prepares to go he seems to shut us out of his mind. When he’s gone, we shake ourselves out of our misery and get on with it: we feed the children, walk the dog, go to our jobs, all the time blocking out thoughts and fears about what he is facing.

Our men chose this way of life; they love it and thrive on it. We made a choice too: to be with them. We hear from civilian friends and family: ‘You knew what you were letting yourself in for,’ or ‘What did you expect when you married a man in uniform?’ But the truth is that most of us did not know what we were getting into. We had only the haziest idea of military life when we walked down the aisle and stood proudly next to our man, splendid in his dress uniform, at the altar.

We are not complaining. Military wives are a stoical band: we get on with it.

Here, in this book, are the stories of a few of us. We don’t claim to speak for all military wives, but we are a cross section: we are women of different ages, with husbands in different services, and of different ranks. These are very personal stories and, by telling them, we hope that all wives will find something they recognise and can relate to. We also hope that anyone who has no experience of military life will read this and understand more of what it is like to marry into the services.

As soon as I heard his voice I knew something was wrong.

‘All right, babes?’ he said. ‘I don’t want you to panic, but I’ve had a bit of an accident.’

My husband, Andrew, was phoning from Afghanistan, on his first tour out there.

The bottom fell out of my stomach when I heard the word ‘accident’, but in my head I could hear this running commentary: he must be all right, as he’s talking to me. He told me he was in hospital with a suspected broken leg. When he put the phone down, I had no idea what to do. I’d gone to stay with my mum in Watford for a few days, taking with me our son Freddie, who was two, and I’d been changing Freddie’s nappy when the phone rang. I didn’t have an information pack with all the emergency numbers, and as we lived in Yeovil, but Andrew was serving with a unit from Plymouth, I didn’t know who to ring. In the end, all I could think of was to ring a friend who had been posted to Germany, and she promised to try to find out for me. There is an official drill, and I should have been informed, but somehow I’d dropped off the radar. My friend texted me to say she was trying to get some information, but I had a terrible night.

The next day I had a phone call from Andrew again. ‘All right, babes? I don’t want you to panic, but I’ve had an accident …’

By now alarm bells were ringing loudly: I hoped he’d got concussion and not a more serious head injury, but he clearly didn’t remember ringing me the day before, and I still hadn’t heard anything official. Eventually I got through to the right welfare number, but there seemed to be no record of him having an injury.

The next day, he rang again: ‘All right, babes? I don’t want you to panic …’

I was really panicking. I asked him if there was anyone else near the phone who could talk to me, but he said the nurse had just wheeled him over and left him there. I was getting desperate, especially when he told me he had a bad headache.

Finally, that afternoon, a liaison officer rang me. Looking back, I should have been making more of a fuss, but I just didn’t know how to. Now I don’t go anywhere without all the right numbers with me.

He was flown back to Selly Oak Hospital, in Birmingham (the centre for treating wounded servicemen). I was told that he had leg, arm and head injuries, caused by an accident when he was on a quad bike.

My dad drove me up to Birmingham while Mum looked after Freddie. When I saw Andrew he had a massive gouge in his head and a long line of stitches up his left arm; then they operated and put pins and plates in his ankle. There were bits of gravel stuck in his face, and where he had been badly shaved there were tufts of hair all over his chin. He was ashen grey, with bags under his eyes, and he looked 15 years older. But he was so pleased to see me. We cuddled and he told me he had a thumping headache.

After the relief of seeing him and holding him, I started crying and berating him. All that emotion, the relief, the fear, everything I’d held in while I didn’t know what had happened, exploded.

‘How could you do this to me? You’ve put me through hell,’ I said.

He was half-laughing, and then he grabbed me and said, ‘I’m really sorry.’

Part of me was happy that at least