Perfect Square

Скачать книги из серии Perfect SquareBurne-Jones

Burne-Jones’ oeuvre can be understood as an attempt to create in paint a world of perfect beauty, as far removed from the Birmingham of his youth as possible. At that time Birmingham was a byword for the dire effects of unregulated capitalism – a booming, industrial conglomeration of unimaginable ugliness and squalor. The two great French symbolist painters, Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, immediately recognised Burne-Jones as an artistic fellow traveller. But, it is very unlikely that Burne-Jones would have accepted or even, perhaps, have understood the label of ‘symbolist’. Yet he seems to have been one of the most representative figures of the symbolist movement and of that pervasive mood termed “fin-de-siecle”. Burne-Jones is usually labelled as a Pre-Raphaelite. In fact he was never a member of the Brotherhood formed in 1848. Burne-Jones’ brand of Pre-Raphaelitism derives not from Hunt and Millais but from Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Burne-Jones’ work in the late 1850s is, moreover, closely based on Rossetti’s style. His feminine ideal is also taken from that of Rossetti, with abundant hair, prominent chins, columnar necks and androgynous bodies hidden by copious medieval gowns. The prominent chins remain a striking feature of both artists’ depictions of women. From the 1860s their ideal types diverge. As Rossetti’s women balloon into ever more fleshy opulence, Burne-Jones’ women become more virginal and ethereal to the point where, in some of the last pictures, the women look anorexic. In the early 1870s Burne-Jones painted several mythical or legendary pictures in which he seems to have been trying to exorcise the traumas of his celebrated affair with Mary Zambaco. No living British painter between Constable and Bacon enjoyed the kind of international acclaim that Burne-Jones was accorded in the early 1890s. This great reputation began to slip in the latter half of the decade, however, and it plummeted after 1900 with the triumph of Modernism. With hindsight we can see this flatness and the turning away from narrative as characteristic of early Modernism and the first hesitant steps towards Abstraction. It is not as odd at it seems that Kandinsky cited Rossetti and Burne-Jones as forerunners of Abstraction in his book, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”.

Bosch

Hieronymus Bosch was painting frightening, yet vaguely likable monsters long before computer games were ever invented, often including a touch of humour. His works are assertive statements about the mental illness that befalls any man who abandons the teachings of Christ. With a life that spanned from 1450 to 1516, Bosch experienced the drama of the highly charged Renaissance and its wars of religion. Medieval tradition and values were crumbling, paving the way to thrust man into a new universe where faith lost some of its power and much of its magic. Bosch set out to warn doubters of the perils awaiting any and all who lost their faith in God. His favourite allegories were heaven, hell, and lust. He believed that everyone had to choose between one of two options: heaven or hell. Bosch brilliantly exploited the symbolism of a wide range of fruits and plants to lend sexual overtones to his themes, which author Virginia Pitts Rembert meticulously deciphers to provide readers with new insight into this fascinating artist and his works.

Burne-Jones

Burne-Jones’ oeuvre can be understood as an attempt to create in paint a world of perfect beauty, as far removed from the Birmingham of his youth as possible. At that time Birmingham was a byword for the dire effects of unregulated capitalism – a booming, industrial conglomeration of unimaginable ugliness and squalor. The two great French symbolist painters, Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, immediately recognised Burne-Jones as an artistic fellow traveller. But, it is very unlikely that Burne-Jones would have accepted or even, perhaps, have understood the label of ‘symbolist’. Yet he seems to have been one of the most representative figures of the symbolist movement and of that pervasive mood termed “fin-de-siecle”. Burne-Jones is usually labelled as a Pre-Raphaelite. In fact he was never a member of the Brotherhood formed in 1848. Burne-Jones’ brand of Pre-Raphaelitism derives not from Hunt and Millais but from Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Burne-Jones’ work in the late 1850s is, moreover, closely based on Rossetti’s style. His feminine ideal is also taken from that of Rossetti, with abundant hair, prominent chins, columnar necks and androgynous bodies hidden by copious medieval gowns. The prominent chins remain a striking feature of both artists’ depictions of women. From the 1860s their ideal types diverge. As Rossetti’s women balloon into ever more fleshy opulence, Burne-Jones’ women become more virginal and ethereal to the point where, in some of the last pictures, the women look anorexic. In the early 1870s Burne-Jones painted several mythical or legendary pictures in which he seems to have been trying to exorcise the traumas of his celebrated affair with Mary Zambaco. No living British painter between Constable and Bacon enjoyed the kind of international acclaim that Burne-Jones was accorded in the early 1890s. This great reputation began to slip in the latter half of the decade, however, and it plummeted after 1900 with the triumph of Modernism. With hindsight we can see this flatness and the turning away from narrative as characteristic of early Modernism and the first hesitant steps towards Abstraction. It is not as odd at it seems that Kandinsky cited Rossetti and Burne-Jones as forerunners of Abstraction in his book, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”.

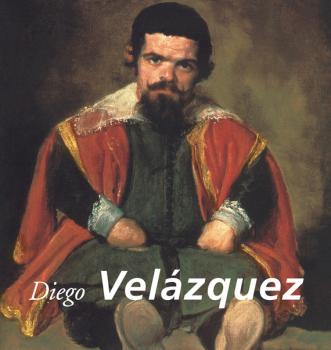

Velasquez

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (June 1599 – August 6 1660), known as Diego Vélasquez, was a painter of the Spanish Golden Age who had considerable influence at the court of King Philip IV. Along with Francisco Goya and Le Greco, he is generally considered to be one of the greatest artists in Spanish history. His style, whilst remaining very personal, belongs firmly in the Baroque movement. Velázquez’s two visits to Italy, evidenced by documents from that time, had a strong effect on the manner in which his work evolved. Besides numerous paintings with historical and cultural value, Diego Vélasquez painted numerous portraits of the Spanish Royal Family, other major European figures, and even of commoners. His artistic talent, according to general opinion, reached its peak in 1656 with the completion of Las Meninas, his great masterpiece. In the first quarter of the 19th century, Velázquez's style was taken as a model by Realist and Impressionist painters, in particular by Édouard Manet. Since then, further contemporary artists such as Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí have paid homage to their famous compatriot by recreating several of his most famous works.

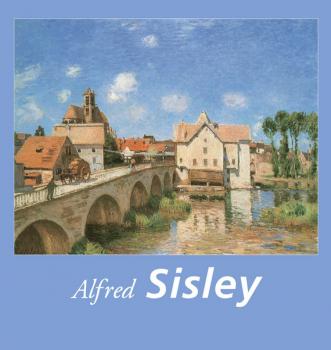

Sisley

A painter of the Impressionist movement, Alfred Sisley was born on October 30th 1839 in Paris but was of British origin. He died on January 29th 1899 in Moret-sur-Loing. Growing up in a musical family, he chose to pursue painting rather than the field of business. In 1862 he enrolled in Gleyre’s studio where he encountered Renoir, Monet, and Bazille. The four friends left their master’s studio in March 1863 to work outdoors, setting their easels to paint the forest scenes of Fontainebleau. Sisley tirelessly chose the sky and water as subjects for his paintings, animated as they were by the changing reflections of light, for his landscapes of the regions surrounding Paris, Louveciennes, and Marly-le-Roi. This was in keeping with the painting styles of Constable, Bonington, and Turnet. Even if he had been influenced by Monet’s work at some point, Sisley drew away from his friend’s style due to his own desire for his work to follow the structure of forms. Sensitive to the changing seasons, he liked to portray spring with its blooming orchards, but it was the wintry and snowy countryside which Sisley was particularly attracted to. His reserved temperament preferred mystery and silence to the splendour of Renoir’s sunny landscapes.

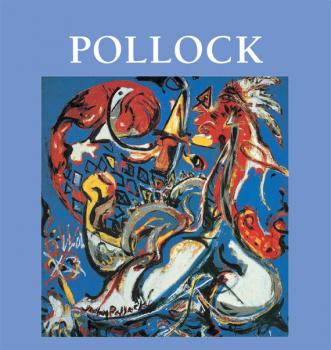

Pollock

Born in 1912, in a small town in Wyoming, Jackson Pollock embodied the American dream as the country found itself confronted with the realities of a modern era replacing the fading nineteenth century. Pollock left home in search of fame and fortune in New York City. Thanks to the Federal Art Project he quickly won acclaim, and after the Second World War became the biggest art celebrity in America. For De Kooning, Pollock was the “icebreaker”. For Max Ernst and Masson, Pollock was a fellow member of the European Surrealist movement. And for Motherwell, Pollock was a legitimate candidate for the status of the Master of the American School. During the many upheavals in his life in Nez York in the 1950s and 60s, Pollock lost his bearings – success had simply come too fast and too easily. It was during this period that he turned to alcohol and disintegrated his marriage to Lee Krasner. His life ended like that of 50s film icon James Dean behind the wheel of his Oldsmobile, after a night of drinking.

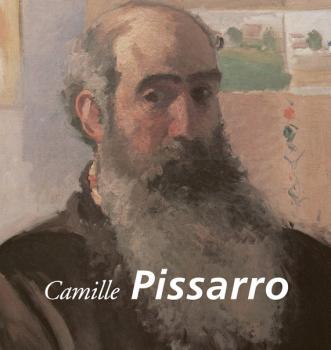

Pissarro

“Father Pissarro”, as his friends liked to call him, was the most restrained of the artists of the Impressionist movement. Perhaps it was his age, being older than his fellow artists Monet, Sisley, Bazille, and Renoir, or rather his maturity, which resulted in his works having such serene and sober subjects and compositions. A man of simple tastes, he enjoyed painting peasants going about their daily lives. However, Pissarro owes his belated fame to his urban landscapes, which he treated with the same passion he used to paint beautiful stormy skies and frost-whitened mornings.

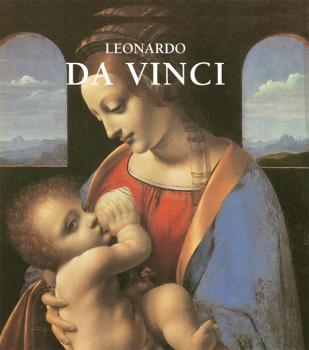

Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo’s early life was spent in Florence, his maturity in Milan, and the last three years of his life in France. Leonardo’s teacher was Verrocchio. First he was a goldsmith, then a painter and sculptor: as a painter, representative of the very scientific school of draughtsmanship; more famous as a sculptor, being the creator of the Colleoni statue at Venice, Leonardo was a man of striking physical attractiveness, great charm of manner and conversation, and mental accomplishment. He was well grounded in the sciences and mathematics of the day, as well as a gifted musician. His skill in draughtsmanship was extraordinary; shown by his numerous drawings as well as by his comparatively few paintings. His skill of hand is at the service of most minute observation and analytical research into the character and structure of form. Leonardo is the first in date of the great men who had the desire to create in a picture a kind of mystic unity brought about by the fusion of matter and spirit. Now that the Primitives had concluded their experiments, ceaselessly pursued during two centuries, by the conquest of the methods of painting, he was able to pronounce the words which served as a password to all later artists worthy of the name: painting is a spiritual thing, cosa mentale. He completed Florentine draughtsmanship in applying to modelling by light and shade, a sharp subtlety which his predecessors had used only to give greater precision to their contours. This marvellous draughtsmanship, this modelling and chiaroscuro he used not solely to paint the exterior appearance of the body but, as no one before him had done, to cast over it a reflection of the mystery of the inner life. In the Mona Lisa and his other masterpieces he even used landscape not merely as a more or less picturesque decoration, but as a sort of echo of that interior life and an element of a perfect harmony. Relying on the still quite novel laws of perspective this doctor of scholastic wisdom, who was at the same time an initiator of modern thought, substituted for the discursive manner of the Primitives the principle of concentration which is the basis of classical art. The picture is no longer presented to us as an almost fortuitous aggregate of details and episodes. It is an organism in which all the elements, lines and colours, shadows and lights, compose a subtle tracery converging on a spiritual, a sensuous centre. It was not with the external significance of objects, but with their inward and spiritual significance, that Leonardo was occupied.

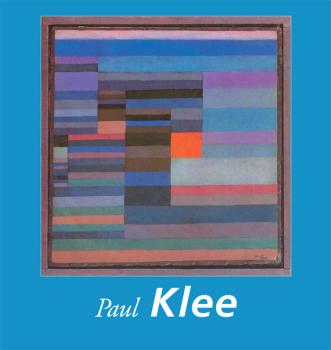

Klee

An emblematic figure of the early 20th century, Paul Klee participated in the expansive Avant-Garde movements in Germany and Switzerland. From the vibrant Blaue Reiter movement to Surrealism at the end of the 1930s and throughout his teaching years at the Bauhaus, he attempted to capture the organic and harmonic nature of painting by alluding to other artistic mediums such as poetry, literature, and, above all, music. While he collaborated with artists like August Macke and Alexej von Jawlensky, his most famous partnership was with the abstract expressionist, Wassily Kandinsky.

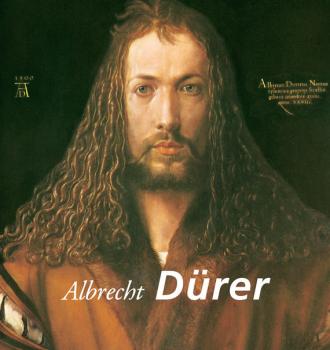

Dürer

Dürer is the greatest of German artists and most representative of the German mind. He, like Leonardo, was a man of striking physical attractiveness, great charm of manner and conversation, and mental accomplishment, being well grounded in the sciences and mathematics of the day. His skill in draughtsmanship was extraordinary; Dürer is even more celebrated for his engravings on wood and copper than for his paintings. With both, the skill of his hand was at the service of the most minute observation and analytical research into the character and structure of form. Dürer, however, had not the feeling for abstract beauty and ideal grace that Leonardo possessed; but instead, a profound earnestness, a closer interest in humanity, and a more dramatic invention. Dürer was a great admirer of Luther; and in his own work is the equivalent of what was mighty in the Reformer. It is very serious and sincere; very human, and addressed the hearts and understanding of the masses. Nuremberg, his hometown, had become a great centre of printing and the chief distributor of books throughout Europe. Consequently, the art of engraving upon wood and copper, which may be called the pictorial branch of printing, was much encouraged. Of this opportunity Dürer took full advantage. The Renaissance in Germany was more a moral and intellectual than an artistic movement, partly due to northern conditions. The feeling for ideal grace and beauty is fostered by the study of the human form, and this had been flourishing predominantly in southern Europe. But Albrecht Dürer had a genius too powerful to be conquered. He remained profoundly Germanic in his stormy penchant for drama, as was his contemporary Mathias Grünewald, a fantastic visionary and rebel against all Italian seductions. Dürer, in spite of all his tense energy, dominated conflicting passions by a sovereign and speculative intelligence comparable with that of Leonardo. He, too, was on the border of two worlds, that of the Gothic age and that of the modern age, and on the border of two arts, being an engraver and draughtsman rather than a painter.