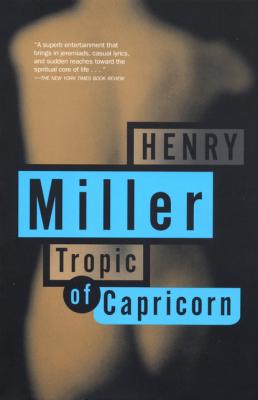

Tropic of Capricorn. Генри Миллер

Читать онлайн.| Название | Tropic of Capricorn |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Генри Миллер |

| Жанр | Эротическая литература |

| Серия | Miller, Henry |

| Издательство | Эротическая литература |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781555846992 |

The whole thing was cockeyed and we were all laughing hysterically and then we began to drink—the only thing they had in the house was kümmel and it didn’t take much to put us under. And then it got more cockeyed because the two of them began to paw me and neither one would let the other do anything. The result was I undressed them both and put them to bed and they fell asleep in each other’s arms. And when I walked out, toward five A.M., I discovered I didn’t have a cent in my pocket and I tried to bum a nickel from a taxi driver but nothing doing so finally I took off my fur-lined overcoat and I gave it to him—for a nickel. When I got home my wife was awake and sore as hell because I had stayed out so long. We had a hot discussion and finally I lost my temper and I clouted her and she fell on the floor and began to weep and sob and then the kid woke up and hearing the wife bawling she got frightened and began to scream at the top of her lungs. The girl upstairs came running down to see what was the matter. She was in her kimono and her hair was hanging down her back. In the excitement she got close to me and things happened without either of us intending anything to happen. We put the wife to bed with a wet towel around her forehead and while the girl upstairs was bending over her I stood behind her and lifting her kimono I got it into her and she stood there a long time talking a lot of foolish, soothing nonsense. Finally I climbed into bed with the wife and to my utter amazement she began to cuddle up to me and without saying a word we locked horns and we stayed that way until dawn. I should have been worn out, but instead I was wide-awake, and I lay there beside her planning to take the day off and look up the whore with the beautiful fur whom I was talking to earlier in the day. After that I began to think about another woman, the wife of one of my friends who always twitted me about my indifference. And then I began to think about one after the other—all those whom I had passed up for one reason or another—until finally I fell sound asleep and in the midst of it I had a wet dream. At seven-thirty the alarm went off as usual and as usual I looked at my torn shirt hanging over the chair and I said to myself what’s the use and I turned over. At eight o’clock the telephone rang and it was Hymie. Better get over quickly, he said, because there’s a strike on. And that’s how it went, day after day, and there was no reason for it, except that the whole country was cockeyed and what I relate was going on everywhere, either on a smaller scale or a larger scale, but the same thing everywhere, because it was all chaos and all meaningless.

It went on and on that way, day in and day out for almost five solid years. The continent itself perpetually wracked by cyclones, tornadoes, tidal waves, floods, droughts, blizzards, heat waves, pests, strikes, hold-ups, assassinations, suicides . . . a continuous fever and torment, an eruption, a whirlpool. I was like a man sitting in a lighthouse: below me the wild waves, the rocks, the reefs, the debris of shipwrecked fleets. I could give the danger signal but I was powerless to avert catastrophe. I breathed danger and catastrophe. At times the sensation of it was so strong that it belched like fire from my nostrils. I longed to be free of it all and yet I was irresistibly attracted. I was violent and phlegmatic at the same time. I was like the lighthouse itself—secure in the midst of the most turbulent sea. Beneath me was solid rock, the same shelf of rock on which the towering skyscrapers were reared. My foundations went deep into the earth and the armature of my body was made of steel riveted with hot bolts. Above all I was an eye, a huge searchlight which scoured far and wide, which revolved ceaselessly, pitilessly. This eye so wide-awake seemed to have made all my other faculties dormant; all my powers were used up in the effort to see, to take in the drama of the world.

If I longed for destruction it was merely that this eye might be extinguished. I longed for an earthquake, for some cataclysm of nature which would plunge the lighthouse into the sea. I wanted a metamorphosis, a change to fish, to leviathan, to destroyer. I wanted the earth to open up, to swallow everything in one engulfing yawn. I wanted to see the city buried fathoms deep in the bosom of the sea. I wanted to sit in a cave and read by candlelight. I wanted that eye extinguished so that I might have a chance to know my own body, my own desires. I wanted to be alone for a thousand years in order to reflect on what I had seen and heard—and in order to forget. I wanted something of the earth which was not of man’s doing, something absolutely divorced from the human of which I was surfeited. I wanted something purely terrestrial and absolutely divested of idea. I wanted to feel the blood running back into my veins, even at the cost of annihilation. I wanted to shake the stone and the light out of my system. I wanted the dark fecundity of nature, the deep well of the womb, silence, or else the lapping of the black waters of death. I wanted to be that night which the remorseless eye illuminated, a night diapered with stars and trailing comets. To be of night so frighteningly silent, so utterly incomprehensible and eloquent at the same time. Never more to speak or to listen or to think. To be englobed and encompassed and to encompass and to englobe at the same time. No more pity, no more tenderness. To be human only terrestrially, like a plant or a worm or a brook. To be decomposed, divested of light and stone, variable as the molecule, durable as the atom, heartless as the earth itself.

It was just about a week before Valeska committed suicide that I ran into Mara. The week or two preceding that event was a veritable nightmare. A series of sudden deaths and strange encounters with women. First of all there was Pauline Janowski, a little Jewess of sixteen or seventeen who was without a home and without friends or relatives. She came to the office looking for a job. It was toward closing time and I didn’t have the heart to turn her down cold. For some reason or other I took it into my head to bring her home for dinner and if possible try to persuade the wife to put her up for a while. What attracted me to her was her passion for Balzac. All the way home she was talking to me about Lost Illusions. The car was packed and we were jammed