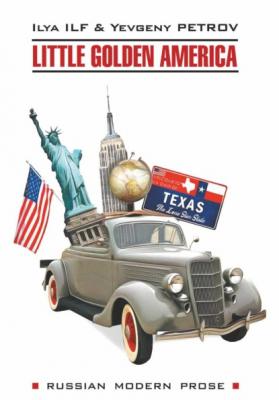

Одноэтажная Америка / Little Golden America. Илья Ильф

Читать онлайн.| Название | Одноэтажная Америка / Little Golden America |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Илья Ильф |

| Жанр | Советская литература |

| Серия | Russian Modern Prose |

| Издательство | Советская литература |

| Год выпуска | 1937 |

| isbn | 978-5-9925-1498-8 |

“The best thing you could do would be to put all these letters back into the suitcase and go back to Moscow. But since you are already here, we’ll have to think up something for you.”

Subsequently we convinced ourselves more than once that the consul could always think up something whenever it was necessary. On this occasion he thought up something grandiose: to send all these letters to their proper addresses and to arrange a reception for all at once.

Three days later, on the corner of Sixty-first Street and Fifth Avenue, in the salons of the consulate, a reception was held. We stood on the landing of the stairway at the second floor. Its walls were hung with immense photographs of the Dnieper Hydro-electric Station, the harvesting of grain with combines, and children’s creches. We stood beside the consul and with undisguised fear looked at the ladies and gentlemen who were walking up from below. They moved in an uninterrupted flow for two hours. These were the spirits called forth by the united efforts of Duranty, Fischer, Eisenstein, and a score of other of our benefactors. The spirits came with their wives – and were in excellent spirits. They were full of eagerness to do everything they had been asked to do in the letters, and to help us learn what the United States was like.

The guests greeted us, exchanged a few remarks, and passed into the salons, where there were bowls of claret cup and small diplomatic sandwiches.

In the simplicity of our souls we thought that when all would come together we, the reason for the occasion, if one may so, would follow into the salon and also raise cups and eat small diplomatic sandwiches. But that is not what happened. We learned that we were supposed to stand on the landing until the last guest departed.

From the salons came gay laughter and noisy exclamations, while we stood endlessly, greeting the late-comers, seeing off those who were departing, and in every other way fulfilling the function of hosts. More than a hundred and fifty guests had gathered, and in the end we did not even manage to find out which of them was a governor and which the native of Proskurov. It was a notable company of grey-haired ladies in spectacles, pink-cheeked gentlemen, broad-shouldered young men, and tall thin young ladies. Since every one of the spirits conjured out of our envelopes represented an indubitable point of interest, we deeply regretted the impossibility of talking at length with each and every one of them.

Three hours later the stream of guests was directed down the stairway.

A fat little man with a clean-shaven head on which glistened large beads of icy sweat came up to us. He regarded us through the magnifying lenses of his spectacles, shook his head, and with much feeling said in fairly good Russian:

“Oh, yes, yes! That’s all right! Mr. Ilf and Mr. Petrov, I have received a letter from Fischer. No, no, don’t tell me anything. You don’t understand. I know what you need. We’ll meet again.”

He disappeared, small, compact, with a remarkably strong, almost an iron body. In the confusion of bidding farewell to guests we could not talk with him and puzzle out the meaning of his words.

Several days later, when we were still lounging in our beds, thinking about where at least we would find the ideal creature so indispensable to us, the telephone rang and the voice of a stranger told us that Mr. Adams was speaking and that he wanted to come right up to see us. We dressed quickly, wondering who Mr. Adams was and what he wanted of us.

Into our hotel room entered the same fat little man with the iron body whom we had seen at the reception in our consulate.

“Gentlemen,” he said, without any preliminaries, “I want to help you. No, no, no! You don’t understand. I regard it as my duty to help every Soviet person who comes to America.”

We asked him to sit down, but he refused. He ran through our small hotel rooms, pushing us now and then with his hard, protruding stomach. The three lower buttons of his vest were unbuttoned and the tail of his necktie stuck out.

Suddenly he cried:

“I am beholden for much to the Soviet Union. Yes, yes, very much! No, don’t talk; you don’t even understand what you are doing there in your country!”

He became so excited that by mistake he jumped out through the open door and found himself in the hall. We had quite a time of it, dragging him back into our room.

“Were you ever in the Soviet Union?”

“Surely!” cried Mr. Adams. “Of course! No, no, no! Don’t say, “Were you ever in the Soviet Union!” I lived there a long time. Yes, yes, yes! I worked in your country for seven years. You spoiled me in Russia. No, no, no! You cannot understand that!”

Several minutes of association with Mr. Adams made it clear to us that we do not understand America at all, that we do not understand the Soviet Union at all, and that in general we understand nothing of anything at all, like newborn calves.

But it was quite impossible to be annoyed with Mr. Adams. When informed of our intention to undertake an automobile journey through the States, he cried: “Surely!” and attained such a state of excitement that he suddenly opened the umbrella which he carried under his arm and for some time stood under it, as if protecting himself from rain.

“Surely!” he repeated. “Of course! It would be foolish to think

that you could find out anything about America by sitting in New York. Isn’t it true, Mr. Ilf and Mr. Petrov?”

Much later, when our friendship had deepened considerably, we noticed that Mr. Adams, after expressing any thought, always demanded confirmation of its correctness and would not rest until he received that confirmation.

“No, no, gentlemen! You don’t understand anything! We need a plan! A plan for the journey! That’s the main thing! And I will make that plan for you. No, no, don’t talk! You cannot possibly know anything about it!”

He suddenly took off his coat, pulled off his spectacles, flung them on the couch (later he looked for them in his pockets for about ten minutes), spread an automobile road map of America on his lap, and began to trace curious lines on it.

Right there before our eyes he was transformed from a wild eccentric into a businesslike American. We exchanged glances. Was this not perchance the ideal creature of whom we had dreamed? Was this not the luxuriant hybrid which even Michurin and Burbank together could not have brought forth?

In the course of two hours we travelled over the map of America. What an exhilarating occupation that was!

For some time we discussed the advisability ofdriving into Milwaukee, in the state of Wisconsin. There you find at once two La Follettes, one a governor and one a senator, and it was possible to get letters of introduction to both of them. An enviable situation! Two Muscovites sit in New York and decide the question of a journey to Milwaukee. If they like, they’ll go there; if not, they won’t!

Old man Adams sat there, calm, clean, self-contained. No, he did not recommend that we go to the Pacific Ocean by the northern route through Salt Lake City, the city of the salt lake. By the time we arrived there, the mountain passes might be in snow.

“Gentlemen!” exclaimed Mr. Adams. “This is very, very dangerous. It would be foolish to risk your lives. No, no, no! You cannot imagine what an automobile journey is.”

“But the Mormons?” we moaned.

“No, no! Mormons – that is very interesting. Yes, yes, Mormons are the same Americans as others. But snow – that is very dangerous!”

How delightful it was to talk of dangers, of mountain passes, of prairies! But even more delightful was it to calculate, pencil in hand, the extent to which an automobile was cheaper than going by railway, the number of gallons of petrol needed for a thousand miles, the cost of dinners, of a modest dinner for a tourist. For the first time we heard the words “camp” and “tourist-room”. Although we had not yet begun the journey we were already concerned about keeping expenses down, and although we had no automobile we were already concerned about greasing it. We began to regard New York as a dark hole from which we must forthwith escape.

When our elated discussion passed into the