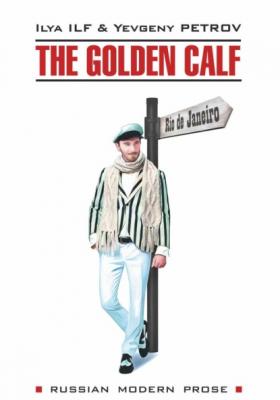

Золотой теленок / The Golden Calf. Илья Ильф

Читать онлайн.| Название | Золотой теленок / The Golden Calf |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Илья Ильф |

| Жанр | Советская литература |

| Серия | Russian Modern Prose |

| Издательство | Советская литература |

| Год выпуска | 1931 |

| isbn | 978-5-9925-1503-9 |

“Well, all kinds of things. A mishmash really. What the newspapers call ‘All things from all places’ or ‘World panorama.’ The other day, for example, I dreamed of the Mikado’s funeral, and yesterday it was the anniversary celebration at the Sushchevsky Fire Brigade headquarters.”

“My God!” said the old man. “My God, what a lucky man you are! A lucky man! Tell me, have you ever dreamt of a Governor General or… maybe even an imperial minister?”

Bender wasn’t going to be difficult.

“I have,” he said playfully. “I sure have. The Governor General. Last Friday. All night. And right next to him, I recall, was the chief of police in patterned breeches.”

“Oh, how nice!” said the old man. “And have you, by any chance, dreamt of His Majesty’s visit to the city of Kostroma?”

“Kostroma? Yes, I had that dream. Wait, wait, when was that? Ah yes, February third of this year. His Majesty was there, and next to him, I recall, was Count Frederiks, you know… the Minister of the Imperial Court.”

“Oh my!” the old man became excited. “Why are we standing here? Please, please come in. Forgive me, you’re not a Socialist, by any chance? Not a party man?”

“Of course not,” said Ostap good-naturedly. “Me, a party man? I’m an independent monarchist. A faithful servant to his sovereign, a caring father to his men. In other words, soar, falcons, like an eagle, ponder not unhappy thoughts…”

“Tea, would you like some tea?” mumbled the old man, steering Bender towards the door.

The little house consisted of one room and a hallway. Portraits of gentlemen in civilian uniforms covered the walls. Judging by the patches on their collars, these gentlemen had all served in the Ministry of Education in their time. The bed looked messy, suggesting that the owner spent the most restless hours of his life in it.

“Have you lived like such a recluse for a long time?” asked Ostap.

“Since the spring,” replied the old man. “My name is Khvorobyov. I thought I’d start a new life here. And you know what happened? You must understand…”

Fyodor Nikitich Khvorobyov was a monarchist, and he detested the Soviet regime. He found it repugnant. He, who had once served as a school district superintendent, was forced to run the Educational Methodology Sector of the local Proletkult. That disgusted him.

Until the end of his career, he never knew what Proletkult stood for, and that made him detest it even more. He cringed with disgust at the mere sight of the members of the local union committee, his colleagues, and the visitors to the Educational Methodology Sector. He hated the word “sector.” Oh, that sector! Fyodor Nikitich had always appreciated elegant things, including geometry. Never in his worst nightmares would he imagine that this beautiful mathematical term, used to describe a portion of a circle, could be so brutally trivialized.

At work, many things enraged Khvorobyov: meetings, newsletters, bond campaigns. But his proud soul couldn’t find peace at home either. There were newsletters, bond campaigns, and meetings at home as well. And Khvorobyov’s acquaintances talked exclusively about vulgar things: remuneration (what they called their salaries), Aid to Children Month, and the social significance of the play The Armored Train.

He was unable to escape the Soviet system anywhere. Even when Khvorobyov walked the city streets in frustration he would overhear detestable phrases, like:

“…So we determined to remove him from the board…”

“…And that’s exactly what I told them: if you insist on the PCC, we’ll appeal to the arbitration chamber!”

Khvorobyov was distressed to see posters calling upon citizens to implement the Five-Year Plan in four years, and he repeated to himself indignantly:

“Remove! From the board! The PCC! In four years! What a crass regime!”

When the Educational Methodology Sector switched to the continuous work-week, and Khvorobyov’s days off became some kind of mysterious purple fifth days instead of Sundays, he retired in disgust and went to live far beyond the city limits. He did it in order to escape the new regime – it had taken over his entire life and deprived him of his peace.

The lone monarchist would sit above the bluff all day long, look at the city, and think about pleasant things: church services celebrating the birthday of a member of the royal family, school exams, or his relatives who had served in the Ministry of Education. But, to his surprise, his thoughts almost immediately returned to Soviet, and therefore unpleasant, things.

“What’s new at the blasted Proletkult?” he would think.

After the Proletkult, his mind would wander to downright outrageous things: May Day and Revolution Day rallies, family evenings at the workers’ club with lectures and beer, the projected semiannual budget of the Methodology Sector.

“The Soviet regime took everything from me,” thought the former school district superintendent, “rank, medals, respect, bank account. It even took over my thoughts. But there’s one area that’s beyond the Bolsheviks’ reach: the dreams given to man by God. Night will bring me peace. In my dreams, I will see something that I’d like to see.”

The very next night, God gave Fyodor Nikitich a terrible dream. He dreamt that he was sitting in an office corridor that was lit by a small kerosene lamp. He sat there with the knowledge that, at any moment, he was to be removed from the board. Suddenly a steel door opened, and his fellow office workers ran out shouting: “Khvorobyov needs to carry more weight!” He wanted to run but couldn’t.

Fyodor Nikitich woke up in the middle of the night. He said a prayer to God, pointing out to Him that an unfortunate error had been made, and that the dream intended for an important person, maybe even a party member, had arrived at the wrong address. He, Khvorobyov, would like to see the Tsar’s ceremonial exit from the Cathedral of the Assumption, for starters.

Soothed by this, he fell asleep again, only to see Comrade Surzhikov, the chairman of the local union committee, instead of his beloved monarch.

And so night after night, Fyodor Nikitich would have the same, strictly Soviet, dreams with unbelievable regularity. He dreamt of union dues, newsletters, the Goliath state farm, the grand opening of the first mass-dining establishment, the chairman of the Friends of the Cremation Society, and the pioneering Soviet flights.

The monarchist growled in his sleep. He didn’t want to see the Friends of the Cremation. He wanted to see Purishkevich, the far-right deputy of the State Duma; Patriarch Tikhon; the Yalta Governor, Dumbadze; or even just a simple public school inspector. But there wasn’t anything like that. The Soviet regime had invaded even his dreams.

“Those same dreams!” concluded Khvorobyov tearfully. “Those cursed dreams!”

“You are in serious trouble,” said Ostap compassionately. “Being, they say, determines consciousness. Since you live under the Soviets, your dreams will be Soviet too.”

“Not one break,” complained Khvorobyov. “Anything, anything at all. I’ll take anything. Forget Purishkevich. I’ll take Milyukov the Constitutional Democrat. At least he was a university-educated man and a monarchist at heart. But no! Just these Soviet anti-Christs.”

“I’ll help you,” said Ostap. “I’ve treated several friends and acquaintances using Freud’s methods. Dreams are not the issue. The main thing is to remove the cause of the dream. The principal cause of your dreams is the very existence of the Soviet regime. But I can’t remove it right now. I’m in a hurry. I’m on a sports tour, you see, and my car needs a few small repairs. Would you mind if I put it in your shed? As for the cause of your dreams, don’t worry, I’ll take care of it on the way back. Just let me finish the rally.”

The monarchist, dazed by his troublesome dreams, readily allowed the sympathetic, kind-hearted young man to use his shed. He threw on a coat over his shirt, stuck his bare feet into galoshes, and went outside with Bender.

“So you think there’s hope for