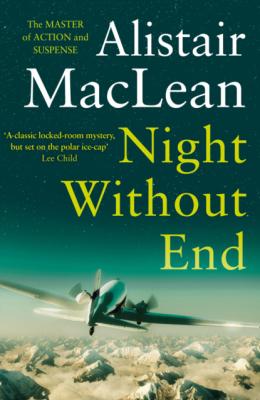

Night Without End. Alistair MacLean

Читать онлайн.| Название | Night Without End |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Alistair MacLean |

| Жанр | Исторические приключения |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Исторические приключения |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9780007289356 |

ALISTAIR MACLEAN

Night Without End

HARPER

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This paperback edition 2005

2

Previously published in paperback by Fontana 1962

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1959

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019 Cover photograph © Stephen Mulcahey

Copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers 1959

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

ISBN 9780006161226

Set in Meridien by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Grangemouth, Stirlingshire

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007289356

2020-09-04

To Bunty

CONTENTS

SIX: Monday 7 p.m.–Tuesday 7 a.m.

SEVEN: Tuesday 7 a.m.–Tuesday midnight

NINE: Wednesday 8 p.m.–Thursday 4 p.m.

TEN: Thursday 4 p.m.–Friday 6 p.m.

ELEVEN: Friday 6 p.m.–Saturday 12.15 p.m.

TWELVE: Saturday 12.15 p.m.–12.30 p.m.

Where Eagles Dare: Alistair MacLean

It was Jackstraw who heard it first – it was always Jackstraw, whose hearing was an even match for his phenomenal eyesight, who heard things first. Tired of having my exposed hands alternately frozen, I had dropped my book, zipped my sleeping-bag up to the chin and was drowsily watching him carving figurines from a length of inferior narwhal tusk when his hands suddenly fell still and he sat quite motionless. Then, unhurriedly as always, he dropped the piece of bone into the coffee-pan that simmered gently by the side of our oil-burner stove – curio collectors paid fancy prices for what they imagined to be the dark ivory of fossilised elephant tusks – rose and put his ear to the ventilation shaft, his eyes remote in the unseeing gaze of a man lost in listening. A couple of seconds were enough.

‘Aeroplane,’ he announced casually.

‘Aeroplane!’ I propped myself up on an elbow and stared at him. ‘Jackstraw, you’ve been hitting the methylated spirits again.’

‘Indeed, no, Dr Mason.’ The blue eyes, so incongruously at variance with the swarthy face and the broad Eskimo cheekbones, crinkled into a smile: coffee was Jackstraw’s strongest tipple and we both knew it. ‘I can hear it plainly now. You must come and listen.’

‘No, thanks.’ It had taken me fifteen minutes to thaw out the frozen condensation in my sleeping-bag, and I was just beginning to feel warm for the first time. Heaven only knew that the presence of a plane in the heart of that desolate ice plateau was singular enough – in the four months since our IGY station had been set up this was the first time we had had any contact, however indirectly, with the world and the civilisation that lay so unimaginably beyond our horizons – but it wasn’t going to help either the plane or myself if I got my feet frozen again. I lay back and stared up through our two plate glass skylights: but as always they were completely opaque, covered with a thick coating of rime and dusting of snow. I looked away from the skylights across to where Joss, our young Cockney radioman, was stirring uneasily in his sleep, then back to Jackstraw.

‘Still hear it?’

‘Getting louder all the time, Dr Mason. Louder and closer.’

I wondered vaguely – vaguely and a trifle irritably, for this was our world, a tightly-knit, compact little world, and visitors weren’t welcome – what plane it could be. A met. plane from Thüle, possibly. Possibly, but unlikely: Thule was all of six hundred miles away, and our own weather reports went there three times a day. Or perhaps a Strategic Air Command bomber testing out the DEW-line – the Americans’ distant early warning radar system – or even some civilian proving flight on a new trans-polar route. Or maybe some base plane from down by Godthaab—

‘Dr